As nearly anyone who works in entertainment law will tell you, there is no such thing as entertainment law. Or, rather, many legal fields comprise entertainment law, and a diverse skillset is needed to achieve success.

Some Law School alumni have pursued one of the many segments of entertainment law, while others use their legal training to work as talent agents or in other roles in the entertainment sphere.

Here, we have asked a few of them for advice about getting into the field and what their jobs entail, as well as the question that everyone asks them: Which famous people do they work with?

Heather Kamins, ’03

Kaims is a business affairs executive at Creative Artists Agency (CAA) who works with actors, musicians, athletes, and brands on myriad projects, including Jennifer Lopez’s line of health and fitness supplements.

Hannah Taylor, ’07

Taylor is an associate at Frankfurt Kurnit Klein + Selz PC in New York City who focuses on advertising, branded entertainment, and intellectual property and whose primary focus is on issues of advertising in social media.

Silvia Vannini, ’08

Vannini is counsel in O’Melveny & Myers LLP’s Century City, California, office, where she focuses on mergers and acquisitions, securities, and general corporate matters both in and out of the entertainment industry.

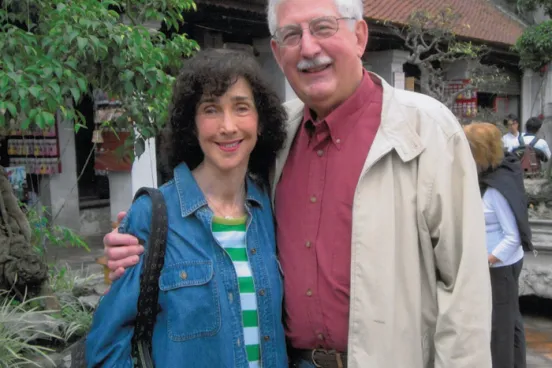

Bruce Vinokour, ’72

Vinokour is a television agent at CAA, where he represents authors such as Carl Bernstein, Ken Follett, Iris Johansen, David McCullough, and Scott Turow, turning their manuscripts or books into deals for TV, such as the John Adams miniseries for HBO or Pillars of the Earth for Starz.

What do you wish someone had told you before you went into the field?

HK: The best thing you can do to break into entertainment law is to gather entertainment law experience any way you can, even if that means working on an entertainment-related case on a pro bono basis or taking a lower-paying job in the field rather than a higher-paying job in a different legal field. When I graduated law school, corporate and transactional work was basically at a standstill. I started as a litigator at a large international law firm, and everyone told me that it would be impossible to make the transition to entertainment law from litigation. But I was determined and sought out one of the few lawyers at the firm with entertainment clients. I begged him to let me assist him with his pro bono cases. This provided me the experience to move to a boutique entertainment law firm in New York a few years later, and, though I had to take a significant pay cut at the boutique firm, that job provided me the opportunity to move in-house at CAA.

BV: At the time I attended law school, I knew nothing about television packaging and had no concept of how television or movie productions were put together. A course in entertainment law would have been very helpful—although there is much more, of course, to the global television marketplace than just the legal aspects of deal-making. Still, I would definitely have welcomed such a course. Today, such a course, I should think, would be most relevant as well, given the digital explosion with so many platforms available for viewing productions.

SV: I wish someone had told me how important law firm culture is. Every law firm (in fact, every local office), has a different culture—a very real and tangible ethos that has significant effect on your work life. I am lucky to have found a law firm with a culture that fits perfectly with my personal style and values.

HT: I didn’t realize quite how many people wanted to practice in this area before I tried it. Turns out, it’s really difficult to break into. It now seems to me that people break into the entertainment law field in one of three ways: Good connections, great experience on the business side, or incredible credentials. If you don’t work at a top firm or you don’t know anyone in the field, try taking a job—even an internship—on the business side. I think it’s very helpful experience for practicing as an entertainment lawyer, but I also think it stands out on a resumé.

In what ways is your line of work different from what you expected?

HT: I am not a “traditional” entertainment lawyer; I am more of a “branded” entertainment lawyer. Basically, if there’s a spokesperson deal between a brand and a celebrity, I am more likely to be representing the brand than the talent. Before I researched and discovered that this line of work existed, I thought all entertainment lawyers worked in film, television, or music, and that they worked for studios or labels, or represented celebrities. Turns out, there’s a lot more you can do if you’re interested in intellectual property, pop culture, the entertainment business, the First Amendment, or how any of those intersect.

SV: I didn’t fully appreciate in law school how fast-paced deals are and how quickly decisions need to be made; it is much more fluid than I expected, and you have to stay on your toes. I think Michigan did a good job setting expectations around complexity and the endurance needed to get deals done and focus on client service.

HK: The entertainment field is much broader than I initially realized. Of course there are lawyers who represent actors, writers, and directors in film and television deals and lawyers who help musicians sign label and tour deals, but there are so many other facets of the industry. I don’t do any of that. At CAA, I work across the agency with a wide spectrum of clients—actors, musicians, athletes, and brands—helping them expand their reach through endorsement, licensing, book publishing, and digital deals. People often think of lawyers as analytical and not creative, but I find that this area of law allows me to be creative and imaginative on a daily basis.

What might a typical day look like for you?

BV: I try to get into the office early in the morning; it’s really a way of life more than a 9-to-5 job. If it’s not a staff meeting in the morning, it’s calls to cities outside of the United States, such as London or Toronto. The day is then filled with meetings and other phone calls; I’m constantly on the phone with producers, actors, authors, and network and studio people, trying to determine the appetite of a particular broadcaster or cable outlet. I work with all the viewing outlets in the United States as well as several networks around the world; I’ve helped set up projects at the CBC in Canada, the BBC in London, and even worked with TF-1 in Paris. I’ve worked on putting together TV series as well, such as Castle, The Good Wife, The Walking Dead, and Rizzoli and Isles, as well as the upcoming Agent X for TNT. And there are deals to be negotiated and contracts to be reviewed in connection with each and every production. In short, the days fly by and then there is usually a drink or dinner with a client, buyer, or executive at day’s end. Finally, there is always—always—reading to be done. It might take the form of an article, a script, a treatment, a manuscript, or a published book. But I am always on the lookout for material that can be the basis of a television production, and that requires constant reading, which is done after dinner and on weekends. But I am not complaining at all. In the end, to see those series or something like the HBO mini-series John Adams come to life, is very, very fulfilling.

SV: Every day is different, but here is what I did one recent day.

- 8 to 9 a.m.: Client call about merger structure

- 9 to 11:30 a.m.: Document drafting

- 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m.: Internal meeting

- 12:30 to 2 p.m.: Lunch with prospective client

- 2 to 4:30 p.m.: Negotiation session with client, target, and opposing counsel

- 4:30 to 4:45 p.m.: Interview with law student

- 4:45 to 7 p.m.: Document drafting

- 7 to 8 p.m.: Client call regarding deal terms

- 8 to 9 p.m.: Preparation for client meeting

HK: One of the exciting things about the job is that no two days are the same. I am lucky enough to work with a wide array of clients on many different types of deals. In a single day I can easily find myself negotiating a book deal with a venerable New York publishing house, advising clients on trademark and naming strategies for a product line, drafting lengthy corporate documents, and meeting with an A-list actress about a strategy for creating her own health and beauty line.

HT: I spend a lot of time on issues relating to social media. While I do everything a branded entertainment or advertising lawyer might do—including structuring and negotiating creative services agreements, commercial production agreements, celebrity talent agreements, and licensing deals—I am also the chair of my firm’s social media task force. In that role, I counsel clients, write, and speak frequently on the legal implications of advertising in social media. It’s an unusual day if I’m not thinking about how to squeeze an important disclosure into 140 characters, or about how to disclose that one of my clients is paying a celebrity to post on Instagram.

To what extent do you interact with well-known authors and other celebrities or well-known brands?

SV: I work with several well-known entertainment companies. A couple of examples: I represented Starz Entertainment in an international joint venture for creation of an over-the-top entertainment platform to be launched as “Starz Play” in the Middle East and North Africa. I also represented Metro Goldwyn Mayer Inc. in the acquisition of a majority interest in Mark Burnett’s One Three Media and LightWorkers Media, to be consolidated into new media venture United Artists Media Group.

HK: I try to interact directly with the clients as much as possible because their talent and creativity always inspire me. Most of the deals I work on are extensions of a client’s core business, so they really are passion projects for the clients. More often than not the clients really want to be hands-on and directly involved every step of the way, including in the negotiation and contract phases. Working with their respective teams of agents, a few representative deals that I have been involved with for clients include Katy Perry’s fragrance line, Jennifer Lopez’s line of health and fitness supplements, Halle Berry’s lingerie line, and Dwyane Wade’s memoir on fatherhood.

HT: One of my favorite assignments is to represent clients before the National Advertising Division (NAD), the self-regulatory body that adjudicates disputes about national advertising. I’ve handled numerous cases at the NAD over the last year, including cases for Gatorade and Clorox. In recent months, I’ve also worked on a major celebrity endorsement campaign for a makeup company, helped clients like AnnTaylor and other major retailers with their licensing and talent deals, and I always review copy for various advertising agencies to advise on IP and truth-in-advertising risks.

BV: I am very fortunate and privileged to work very closely on behalf of a number of authors and estates, including Carl Bernstein, Robert Caro, Ken Follett, Fredrick Forsyth, Joanne Fluke, David Ignatius, Iris Johansen, David McCullough, Scott Turow, among others, and with the estates of Raymond Chandler and James Clavell. I don’t make their deals with the publishing houses—that is done by their literary agents—but once the manuscript is written, that is when I get involved trying to sell that material as the basis of a movie for television, a continuing one-hour series, or even an event mini-series.