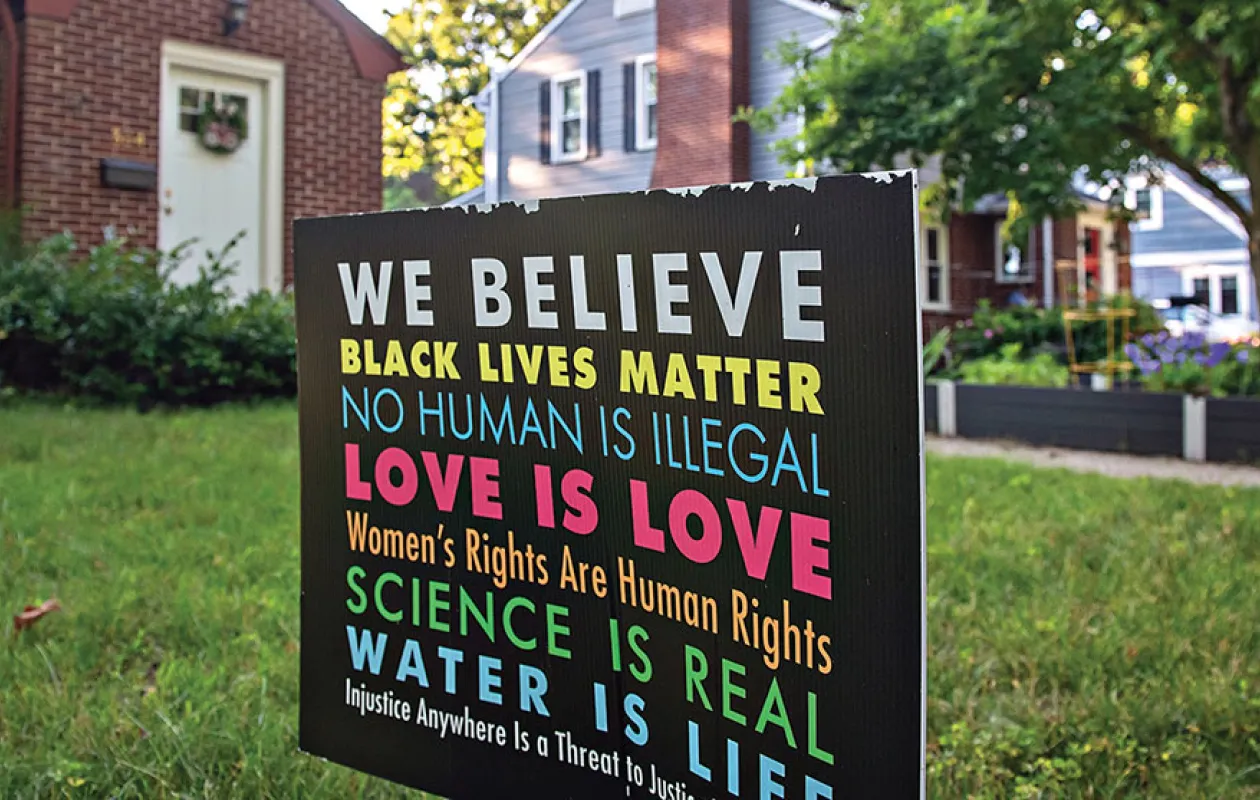

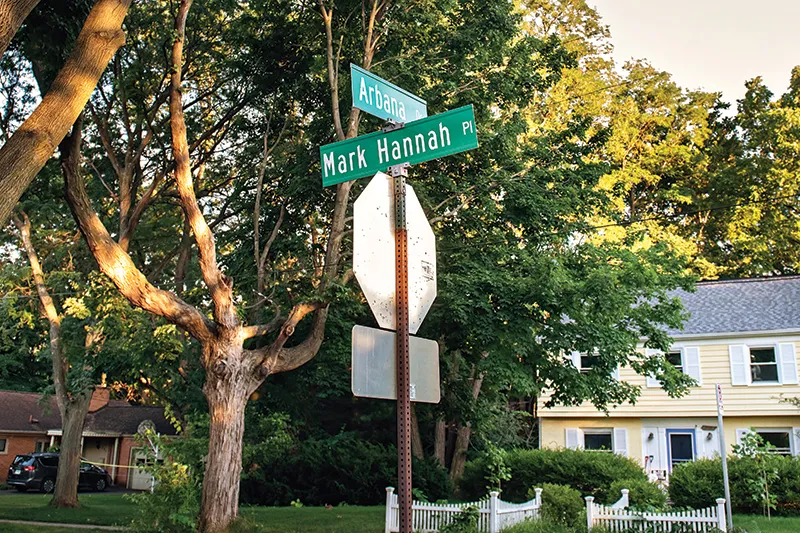

The Hannah neighborhood near downtown Ann Arbor is relatively small, comprising 44 homes built during the 1940s. Dotting some of the lawns are signs that reflect the progressive politics of residents: “Hate Has No Home Here,” reads one; “Black Lives Matter,” reads another. But that welcoming impression took a hit when neighbors started to learn last year that the deeds to their homes contain racist covenants once used for decades to exclude non-whites. The common reaction? Shock.

“One neighbor was a white man whose partner is a person of color, and he was extremely shocked to hear that he lives on a lot that was covered by this restriction,” says 3L Nina Gerdes, a member of the Law School’s Civil Rights Litigation Initiative (CRLI). “He actually found his closing documents and saw the covenant. He was upset that it would be on a property that he shares with his wife and his family members, who are people of color.”

The CRLI, led by Professor Michael Steinberg, teaches students through hands-on lawyering experience in litigation and projects addressing various civil rights issues. Earlier this year, a group of CRLI students worked alongside Justice InDeed—a collaborative of U-M faculty and students and Washtenaw County leaders and citizens—to repeal and replace racist covenants.

Difficult as it may be to believe, in a city known for its progressive politics and blend of residents from all over the world, such covenants are not rare in Ann Arbor. From the early 1920s to the early 1950s, developers routinely included them in deeds to enforce segregation. They were a reaction to Buchanan v. Warley, the 1917 US Supreme Court case that struck down an ordinance restricting where Blacks could live. Unlike legal statutes, however, private covenants were not illegal and started appearing in deeds for homes around the country.

“A lot of lenders would not loan to developers unless they included that language, and other developers themselves may have chosen to put in the language,” says Susan Fleurant, ’22, a former CRLI student-attorney and Justice InDeed volunteer. The developer of the Hannah Subdivision imposed the covenants in 1947, shortly before the 1948 US Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, which held that courts could no longer enforce such covenants. In 1968, they were outlawed with the passage of the Fair Housing Act.

Righting 75-year-old wrongs

So why work to amend deeds when the covenants are unenforceable and illegal? That question came up more than once, even, initially, among students and community members. The reason is twofold.

“First, there’s explicitly racist language in these covenants,” says Fleurant. “People are still seeing those documents and reading that language, and it still has an effect in the present day—even if it’s not legally enforceable. Thinking about the stigma that comes with reading that language and feelings of being unwelcome, these covenants still do cause harm. Second, it’s one part of an ongoing conversation about racial segregation and housing and the lasting impact that has had on opportunity, generational wealth, and access to educational opportunities.”

The covenants took various forms, with some excluding Blacks (except for “domestic servants” living in the home with white owners), some excluding people of African or Jewish descent, and others specifically allowing for Caucasian/white-only residents. If someone tried to sell a home to a member of one of the excluded groups, a neighbor could sue to void the sale. It’s not known how many potential homeowners in Ann Arbor the covenants affected.

The work of CRLI and Justice InDeed is part of a broader movement in communities across the country to remove discriminatory covenants. The Hannah neighborhood is believed to be the first in Michigan to repeal such covenants. Not only did the groups work to repeal the covenants, they also sought to replace them with inclusive language (see the sidebar). Homeowners can now see both the old and new language in their deeds.

“We didn’t want to erase the history,” says 3L Laura Durand. “We need to remember that this happened and at the same time say this is no longer consistent with our values. We don’t want to whitewash it or pretend like it never happened.”

Helping a community recognize and rectify its past

Durand adds that the groups approached their work in various ways. “We have multiple methods of trying to address the problem: legislation, litigation, education, communication, and community organizing,” she says. Late last year, she testified in support of legislation that would help homeowners in Michigan repeal similar covenants in their deeds. “There are other states that have already passed legislation, like Minnesota and Washington,” she notes.

But it was the community organizing work that resulted in the amended deeds in the Hannah neighborhood.

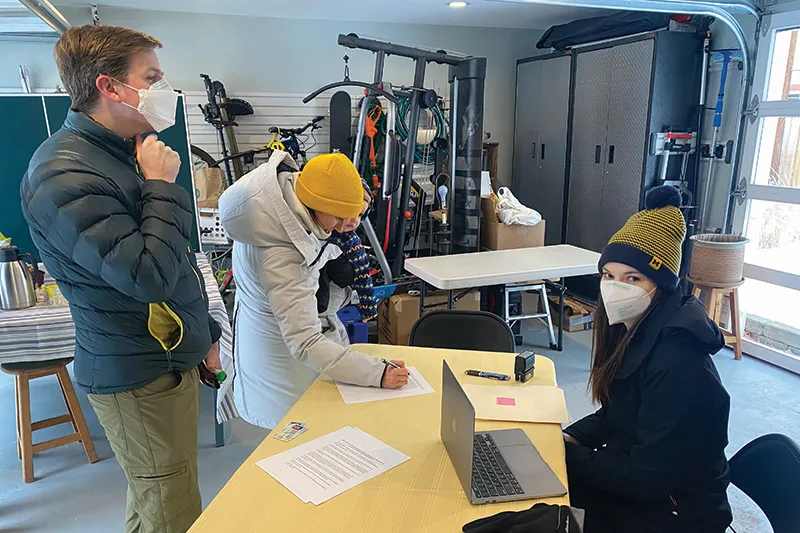

“We needed to get more than 50 percent of the neighborhood on board if we wanted to amend the documents,” says Gerdes, who added that the neighbors were the driving force behind strategizing for change. Working with the students and Steinberg, a small group of neighbors began to reach out to others to meet and discuss the situation. “In early February, we did neighborhood canvassing, so I joined some of the Hannah neighbors and we went door to door asking if residents had any questions or anything that we could clarify.”

The effort resulted in far more than the 50 percent goal required to repeal the covenant. More than 85 percent of homeowners signed the petition to repeal in a single weekend. The amendment faced no opposition by anyone from the subdivision.

“Today, a neighborhood came together and reckoned with Ann Arbor’s history of segregation and racial discrimination,” said Alexandria Nichols, ’22, at the time. “Not only did homeowners repeal a hateful whites-only restriction on their property, but they replaced it with a provision celebrating inclusiveness and banning discrimination.”

She had done some community organizing before working on this project. “But it was definitely interesting doing it from a legal perspective,” she says.

On February 24, the homeowners delivered the amendment to the Washtenaw County Register of Deeds that repealed and replaced the covenant.

“The register of deeds, Larry Kestenbaum, has been very helpful on this issue and has wanted to do something about this for a long time,” says Steinberg. “He was so grateful for what the students and our community collaborators were doing.”

There’s more work to be done

Steinberg added that work continues on a map that shows where racially restrictive covenants exist. In Washtenaw County alone, 121 neighborhoods have such covenants. “Eventually, our goal is to have a Zillow-type map where you can click on your house in Washtenaw County and find out if there’s a racially restrictive covenant—and, if so, we want to provide an easy way for you to amend it.”

Additionally, CRLI and Justice InDeed are developing a toolkit that will allow other neighborhoods to repeal and replace their covenants.

The work might be more complex than that in the Hannah neighborhood, says Gerdes. “It was deceptively easy. Their covenant covered the whole community and also had a voting mechanism. So now we’re doing research and strategizing about how to combat those that don’t have voting mechanisms or that are restrictions on individual lots rather than communal restrictions.”

CRLI and Justice InDeed also are working on a lawsuit that would require the repeal of a racially restrictive covenant before the register of deeds records a transfer of property.

All of this work could not have been done without the work of CRLI students, says Steinberg, listing everything from community organizing and researching issues for litigation and legislation to speaking to the community and press.

“The CRLI students are very motivated to work for social justice, and they were especially excited when we earned a victory in the Hannah Subdivision,” says Steinberg. “They’re out there educating the community and policymakers about the systemic nature of housing discrimination and how racial covenants and other racist policies have stripped generations of people of color of wealth and opportunity. This education is a critical first step toward enacting policies to repair the harm. The project and our students give me a lot of hope.”