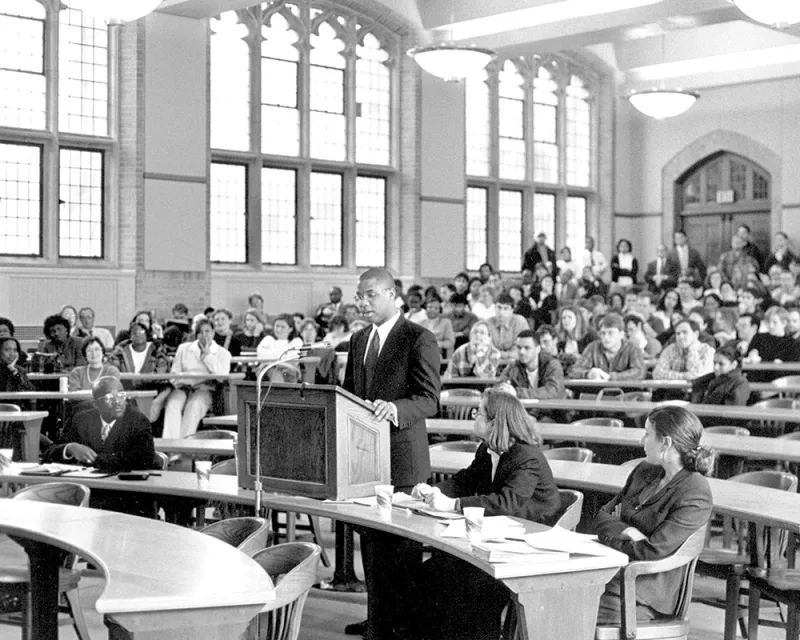

In the late afternoon of March 24, members of the Law School community filed noisily into room 100 of Hutchins Hall (Honigman Auditorium), looking for seats as they talked with friends and colleagues. In contrast, an odd calm prevailed at the front of the room. Two young men in suits and ties sat quietly at separate tables, facing forward and seemingly undisturbed by the commotion surrounding them.

Then silence fell over the room as the final round of the 100th Henry M. Campbell Moot Court Competition began. Three federal judges made their way into the room, and arguments began in the hypothetical US Supreme Court case of Richards v. Danforth.

On behalf of the petitioner, Arthur Etter, ’25, stood before the judges and started to lay out his argument.

Within minutes, one of the judges interrupted with a question. Etter, who had spent months preparing for such interruptions, replied to that question and the many others that were lobbed his way during his 30-minute presentation.

“I focused on staying calm and returning to my best arguments,” he later said of the back-and-forth with the judges. “Once the bench started warming up and I could tell what issues the judges were interested in, I tailored my arguments to focus on those areas.”

Likewise, Connor Mulvena, ’25, made his argument on behalf of the respondent while fielding a barrage of questions from the Hon. Rachel Bloomekatz of the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, the Hon. Toby Heytens of the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, and the Hon. David Stras of the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

Later, Judge Stras commended each of them for maintaining their composure "even though we were beating you up."

In the end, Etter was named the winner and both listened intently as the panel provided specific, constructive feedback about their oral arguments.

The event capped this year’s student-run competition, which began the previous fall with 122 2L and 3L students writing and rewriting briefs and competing in elimination rounds of oral arguments.

They addressed the hypothetical case prepared by the competition’s student board. Neither Etter nor Mulvena knew which side he would represent until a coin toss before the final moot court.

“It’s hard to think of better training to be a lawyer,” says the Hon. Joan Larsen of the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and the adviser to the Campbell program. “The whole point of law is the peaceable resolution of conflicts; to accomplish that goal, we need to teach students to listen to, understand, and engage with ideas they might not instantly agree with.”

Real-life practice

Since the 1925–1926 academic year, Michigan Law students have taken their place before a panel of judges to argue opposing sides in the Campbell moot court. They were far from the first to participate in such competitions—moot courts for law students have been around since medieval England.

However, they were the first to participate in the Law School’s oldest student competition and one of its highest honors. Over the past 100 years, the popularity of the competition has persisted despite the burden of classwork and an array of other extracurricular offerings.

“Campbell provides a unique opportunity to get real-life appellate litigation practice,” says rising 3L Anna Kallmeyer, chair of the Campbell Moot Court Board for the 2024–2025 academic year. “It's not super intuitive how to engage with a panel of judges, how to argue your case in a way that's persuasive and assertive but also respectful. Campbell gives students the opportunity to formulate arguments, articulate those arguments in a low-risk environment, and build those skills before they graduate.”

That was precisely the experience of the Hon. Roger Gregory, ’78, of the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Judge Gregory competed as a 2L student; he and his partner advanced to the quarterfinal round.

“I had my first jury trial in my third year because I was a volunteer for an Ann Arbor legal aid trial in Ypsilanti,” says Gregory, who has returned to Ann Arbor to serve as a Campbell judge on three occasions. “It was a good experience having done moot court as a student to at least stand in front of the judges and make your argument. I wouldn't have traded the experience for anything.”

The competition also gives students a chance to determine whether to pursue a career in appellate law, says Caroline Flynn, ’13, Supreme Court counsel at Earthjustice, former assistant to the solicitor general in the US Department of Justice, and a former clerk to Chief Justice John Roberts on the US Supreme Court.

Flynn, a semifinalist in the 2013 competition, had taken the Legal Practice Program during her 1L year as well as appellate seminars.

“Campbell helped me see if I had the chops to do appellate work,” she says, adding that the practice of arguing both sides of the case was valuable.

“The exercise of writing briefs and then taking the opposite side of an issue was really interesting because, of course, when you're writing your own brief you think of the strongest arguments for the other side. So it's great to then be able to turn around and seize upon those arguments to your advantage.”

The Hon. Joan Larsen, US Court of Appeals for the Sixth CircuitIt’s hard to think of better training to be a lawyer.

A competition is born

While moot court organizations existed at the Law School in its earliest years, none of them endured in a consistent way. But in 1924, Law School students made another attempt and organized 20 clubs of first- and second-year students who would argue cases against other members of their club under the direction of a third-year student. Professor Herbert Goodrich outlined the process and goals for the clubs in a March 27, 1924, article in Michigan Alumnus magazine:

"Arguments will start in a few days and continue for several weeks, until each member of the various clubs has participated in at least one argument. With this start it is expected that the work can begin without delay at the beginning of the school year next fall, when a more elaborate program can be undertaken. It is hoped at that time, too, to begin a series of inter-club contests, in addition to the arguments between counsel in the same club."

The first edition of what we now know as the Campbell Moot Court Competition took place during the 1925–1926 academic year. It was organized around four “case clubs”: the Holmes, Kent, Marshall, and Story clubs.

In 1927, the competition was named in honor of Henry Monroe Campbell, who had graduated from the Law School in 1878 and died in 1926. He was a partner in the firm that eventually became Detroit-based Dickinson Wright, and he also served as legal counsel to the University of Michigan's Board of Regents for several years.

True to the vision Goodrich described in Michigan Alumnus, a more elaborate program developed in its early years.

According to a set of rules published in 1931, participating students were divided into the four clubs, with each club comprising approximately 32 first-year students and eight second-year students. Each student was paired with another member of the club.

First-year students competed within their club while second-year students competed against other clubs, briefing and arguing hypothetical cases developed by the faculty. The second-year winners received $100 while the first-year winners received a three-year subscription to the Michigan Law Review.

From the very beginning, it was clear that the competition benefited students in several ways: They became familiar with the resources of the law library; they learned from the feedback to their written and oral argument; and they saw the law they were studying brought to life. In short, before Law School clinics, externships, and pro bono work gave students real-world experience, Campbell provided a learning opportunity outside the classroom.

Evolution of the program

By 1953, the number of student-managed clubs—all named for prominent Michigan jurists, including former Law School dean Henry Bates and former U-M president Henry Hutchins—had grown to 16.

And according to updated rules published in 1954, faculty assigned students to clubs during the first week of school (students usually remained in the same club for the duration of law school). In the two-year competition, the 32 participants who finished highest in their first year advanced to the Campbell competition in their second year. The winner among the second-year students took home the Campbell award.

“At the time I was a student, the second-year program was a natural outgrowth of the first-year program,” says Theodore St. Antoine, ’54, the James E. and Sarah A. Degan Professor Emeritus of Law and Law School dean from 1971 to 1978.

St. Antoine, who won the 1953 Campbell moot alongside teammate Donn Miller, ’54, says each member of both teams had the opportunity to make an oral argument in the final round. When including a rebuttal for the opening team, that totaled five oral presentations.

“Donn and I decided which cases or precedents each of us would stress in the oral presentation so that we would not be hammering the same ones,” St. Antoine says. “It was very much team oriented, which was a wonderful opportunity for students to engage in a joint effort. Law itself is so much a matter of collaboration. I think one of the great lessons to be imparted in a law school is the importance of working with people. It’s much more reflective of the way law is actually practiced.”

In addition to the first- and second-year students, third-year students participated by acting as club leaders, advisers to students, and judges, receiving credit if they successfully completed three cases in their club work. The highlight of the events was the annual Case Club Day, when the final competition was held and the Campbell Award was given at an evening banquet.

From teams to individuals

Subsequent years saw changes in the program, such as the number of clubs and students that participated and the format of the competition.

For example, in 1977, third-year students were allowed to compete, and the hypothetical case wasn’t so hypothetical. It was a precursor of a major US Supreme Court reverse discrimination case decided in 1978, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. However, the Campbell case returned to its hypothetical roots in following years.

Major changes came in 1994; that year, new Law School Dean Jeffrey Lehman replaced the case clubs when he established the Legal Practice Program to teach legal writing, research, and advocacy to first-year law students. However, it did not spell the end of the Campbell competition, which continued unabated.

Over the years, the makeup of the teams fluctuated: From 1926 to 1974 (with the exception of 1944), each team comprised two students; from 1975 to 1989, each comprised up to four students; and from 1990 to 2010, the competition reverted to two-person teams.

In 2011, the competition moved to a hybrid model that continues today; students work as teams in the preliminary rounds and then advance as individuals. Larsen said that change was made for two reasons; first, it more accurately simulates oral argument.

“In no actual court do two people stand up to represent one client,” she says. “Although you might have somebody sitting at counsel table with you, one person stands up and knows the whole case.”

Second, Larsen says that teammates were not always equally matched, which could prevent a worthy student from advancing to the final round.

“We felt like we were not always able to advance the best advocates to the semifinal and final rounds. The goal of the competition is to highlight Michigan's very best oralists.”

Adapting yet enduring

A major one-time change occurred in April 2021 as COVID-19 upended many aspects of normal life, including the Campbell competition.

“The first year of the pandemic, we got lucky because we held the arguments very early—right before campus closures,” says Larsen. “But then, in the following year, we had to pivot to Zoom and had virtual Campbell.”

The changes came with a silver lining, though: a mentorship program that matched participants with alumni who coached students on appellate advocacy and oral argument before the preliminary round. The online program, while not always perfect, allowed the Campbell moot court to continue its unbroken line of competitions.

“That year of law school was isolating in many ways because we were all doing classes on Zoom from our bedrooms,” says Victoria Clark, ’22, who won the 2021 competition and now is an associate at Covington and Burling LLP.

“At the end of the competition, what stood out to me the most was how many people had come together to help me throughout the months-long process. I made connections with people I never would have if I hadn’t competed. As a practitioner, I see how the legal profession can sometimes feel isolating and like we’re doing things all on our own. I try to remember the lesson of how much better we do, and how much more enjoyable the experience is, when we rely on our colleagues.”

The event returned to its in-person format in 2022.

As the competition enters its second century, its mission to give students practical lessons in the art of appellate advocacy continues.

“Campbell is a great learning experience regardless of whether you compete in the prelims or make it to the final round,” says Etter, the winner of the 100th Campbell moot court. “I remember watching the final round as a 1L and thinking it was interesting, impressive, and intimidating. I had no idea I would end up competing, much less making it all the way to the end.”

For 100 years, Michigan Law students have participated in the Henry M. Campbell Moot Court Competition, the annual student-run event that has given generations of participants insights into appellate advocacy.

Scroll to continue reading about the judges, the questions, and the memories from Campbell participants.