Name, image, likeness (NIL)—three words that have created enormous changes for student-athletes and collegiate sports. While the concept of NIL, sometimes jokingly referred to as “Now It's Legal,” has been increasingly in play in recent years, the US Supreme Court’s June 2021 ruling in NCAA v. Alston focused attention on student-athletes earning compensation in a variety of ways, including licensing their name, image, and likeness.

These developments have complicated discussions around how universities should approach the fundamentals of scholarships, academic achievement awards, and implementing NIL while continuing to preclude outright pay for play. Many continue to question whether students should be allowed to earn any compensation in college athletics. As with other new and emerging areas of law, significant implementation and compliance challenges are yet to be revealed and solved.

We spoke with two Michigan Law alumni—one historically in favor of and one against compensation for student-athletes—who have engaged on this topic over the past several years in friendly debate with each other.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

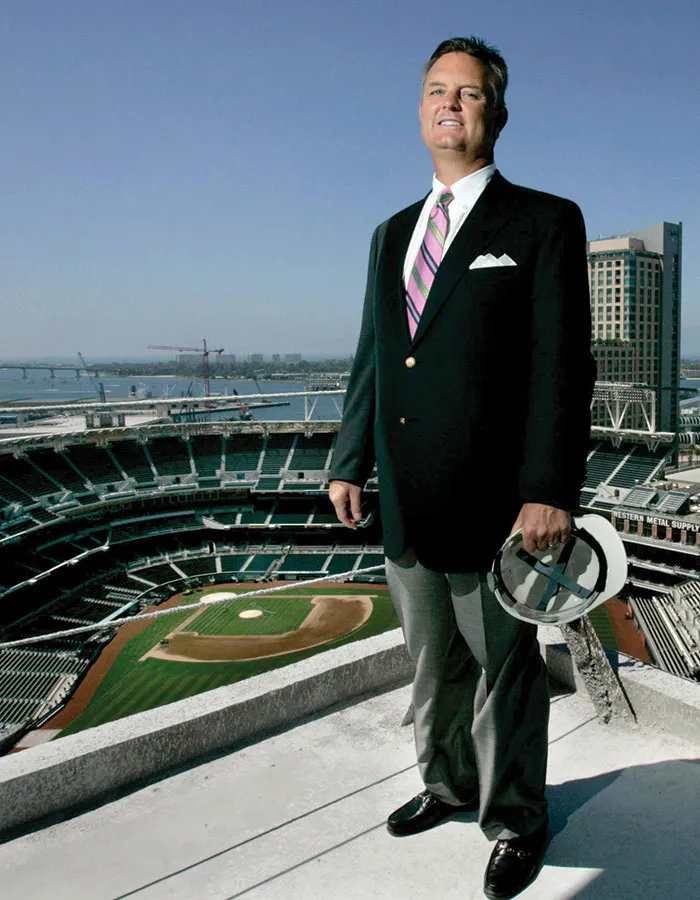

Todd Anson, ’80, serves as vice chair of the Central Michigan University (CMU) Board of Trustees and is managing member of Anson Family Holdings LLC. A leader in the group that encouraged Jim Harbaugh to accept the position of head football coach at U-M, Anson has helped in the development of NIL platforms, known as collectives, for both CMU and U-M. The latter, called Hail! Impact, launched in March and aims to provide student-athletes with financial opportunities. Anson strongly supports the movement to allow student-athletes to share the economic pie, which he believes is more fair and levels the playing field with programs that don’t follow the rules. But he sees room for improvement in its execution and hopes to see more structure imposed around NIL.

When did we start to see big money flowing into college athletics?

The Big Ten's formation of the Big Ten Network in 2006 cascaded across college athletics and resulted in huge TV money flowing toward the schools. The five major conferences found that this radically ramped up the revenues coming into the universities for football and basketball. At U-M, the TV revenue has risen dramatically since 2006, to more than $50 million per year. The business of distributing and broadcasting these games is one of the most profitable things right now in the media space, and the NCAA and schools do not share the wealth.

Schools primarily spend money on salaries for coaches and on facilities. Some NFL teams don’t have training facilities that are anywhere close to what a top-flight college program has. The universities’ commitment to investing all of that TV money in coaches and facilities is how they compete for student-athletes. But coaches have benefitted the most.

It's been so unfair for so long to the student-athletes. In professional sports—the NBA, MLB, NFL, and NHL—the athletes, the talent on the field, get half of all revenues from the sport. In college football, it's probably less than 1 or 2 percent because the only value that the student-athletes are getting out of it is their scholarships. There’s a maximum of 85 full-ride scholarships on a football team.

What are the current rules and regulations around NIL?

What we have are 38 state statutes [as of mid-May] that strongly encourage and support NIL opportunities, making it illegal for those who control student-athletes to block their access to those opportunities.

The NCAA rules underneath are, one, no pay for play and, two, no improper inducements, which means you can't pay an athlete to come to your school. You can pay them once they get there. You can't have a linkage between the payments and their performance. So if an athlete quits a sport after you've signed her or him, you still have to pay for them that one year.

But there is a lot of chaos right now. For example, the University of Florida signed a quarterback by the name of Jaden Rashada in December 2022. He received a $13.85 million NIL package, which quite clearly seems to be an improper inducement. A player cannot know what his or her NIL package is going to look like before they attend the school. But the fundraising blew up before he even got to the University of Florida. [Rashada has since committed to Arizona State.] So we're at this really awkward time for everybody.

How do you suggest that universities impose more order?

I've long been a proponent of a structure whereby the coaches are held contractually accountable for rules violations that occur on their watch. That includes a potential clawback of some, or a substantial portion, or all of the coach’s salary back to the dates of the most significant violations.

So coaches should be expected to sign an employment contract that says their compliance with NCAA rules will be mediated or arbitrated, and everybody agrees to subpoena power. That would be the biggest measure to ensure the integrity of NIL platforms. And it would be something the NCAA would do. Unless we address that, I'm not that optimistic that we're going to be sailing in calm NIL seas.

You are participating in developing collectives for NIL, which pool donor money to finance opportunities for student-athletes. Is that a possible solution to some of the current problems?

I’ve been involved for the last year and a half in creating a nonprofit collective that empowers student-athletes to work for local charities. That work has merged into Andy Johnson and Chin Weerappuli’s Hail! Impact. We expect the steam, the heat, and the initial thrust to be football, but this is a platform that supports every Michigan sport.

Everyone will benefit from Hail! Impact. It elevates local charities with engagement and funding. And the student-athletes get a stipend by making appearances at fundraisers, doing things with kids, and so on and so forth. It also has a deep educational aspect for the student-athletes, who learn about financial planning, saving, investing, and branding—all the things that business people have to be aware of.

So this is a separate organization, independent of the University?

Yes. Universities have to be careful because there has to be separation from collectives like this. There's got to be distance between the two. The whole point of NIL is that third-party money flows to the athletes. It is a clear NCAA violation to have a situation where the university owns or runs NIL.

Do you anticipate that the rules around compensation for student-athletes will evolve over time and that we’ll get past the “chaos”?

I think they're going to evolve as to NIL. They haven't ripened yet; we don't even have a full set of rules. It's literally still a new frontier.

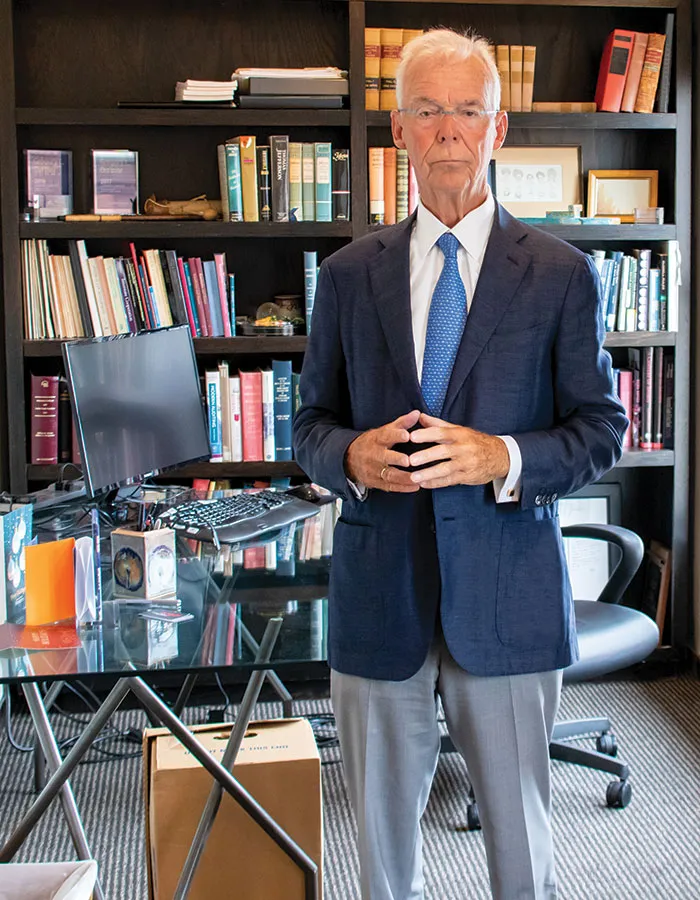

Greg Curtner, ’70, is a partner at Riley Safer Holmes & Cancila, where he has represented the NCAA for more than 20 years. He has studied and written articles about the antitrust implications of compensating student-athletes, including a widely read op-ed in The Hill, “Ending amateurism would be disastrous for student-athletes,” published in 2021. While the NCAA is a client of the firm, Curtner stresses that his responses below are his personal take on NIL, not the NCAA’s.

You have extensive knowledge of antitrust cases related to compensating student-athletes. What is the difference between NIL and pay for play?

NIL licensing raises one set of issues while compensation for services, or pay for play, should be a different set of issues. I try to maintain that distinction.

A lot of the analysis in these cases turns on whether the antitrust laws require compensation for services. And yet, other times they're addressing NIL as the property interest. Judge Claudia Wilken, the district court judge in the Alston case and the earlier O’Bannon and Electronic Arts cases, used NIL as a jumping-off point but then broadened the analysis to compensation in general.

Now that NIL deals are becoming common, what is your impression?

It's clearly open hunting at some schools. There are people linking NIL, either explicitly or implicitly, to recruiting a student-athlete to come to a particular school. [See the Jaden Rashada example, above.]

Not only is there opportunity for corruption in recruiting, there's also substantial opportunity for exploitation of young people. Having a sophisticated commercial advertiser/promoter negotiating with a high school kid seems unfair. They fall for a big number, and it turns out that is not always to be true. The NCAA is likely to take some enforcement actions.

Will the fact that most states have passed NIL laws help with problems like that? Does the NCAA have a role?

I don't think state-by-state regulation is a good solution after high school. The NCAA has managed for many years to live with state laws. It usually finds a way to have its voice heard. But many people think that the only real solution is for Congress to set the rules. And maybe that's where we're going. I think that's where the NCAA is going. But we all know that there is no telling what Congress will do.

You’ve written about the value of amateurism in college sports. Why is that?

Amateur competition is really a wonderful thing. It's an important part of why we are drawn to this form of competition. Competition for the sake of competition, which is what amateurism is, is a beautiful aspect of being human.

Some preservation of amateurism also supports team unity. It used to be that the team, whether it was the star quarterback or the reserve lineman, all got the same scholarship and non-scholarship players could earn a scholarship. We are at risk of losing that unity when the star quarterback is getting millions and the reserve lineman is getting tuition, room, and board. As Bo Schembechler always said, “The Team, the Team, the Team.”

If you talk to people who have been student-athletes, years later most will say that was the best experience of their life. They've been successful in business, or in whatever else they have done, because of the discipline that they learned as a student-athlete and the network of friends they made.

My personal view is that amateurism is still an important value and that we should not professionalize college sports more than we already have. Perhaps we have gone too far already.

Can NIL and amateurism coexist?

There’s a model that I think the NCAA could consider where you might have some conferences—the Big Ten and the SEC, for example—where all the players receive scholarships that are more or less unlimited and NIL deals are more or less unlimited. And you may have other conferences where they maintain a distinct amateur nature. The Ivy League has a version of that, which works pretty well. And there may be leagues, like the Mid-American Conference, where something like half of each team are allowed to be professionals.

To me, and I may be alone here, that might preserve the essence of amateur sports. Most people are only talking about how to compensate more while trying to avoid outright pay for play.

We can’t lose sight of academics. College is about academics, after all. Where does that fall in this discussion?

The NCAA for the last 20 years has worked vigorously to try to engage in academic reform, to restrict athletic dorms, “jock classes,” and the like. Now each team has to have a certain Academic Progress Rating or they can't participate in postseason play. Eventually, if they don't measure up, they lose scholarships. That motivates coaches, right? While “one and done” still happens, an entire team can’t be composed of athletes who aren’t also students. Graduation rates have gone up for men, women, and Black athletes. I don’t think the NCAA gets enough credit for that.

I've spent a lot of time with James Heckman, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, on these kinds of issues. We obtained two sets of data from the Department of Education that had a huge amount of information over two different seven-year periods with some 13,000 students, both student-athletes and non-student-athletes. And real progress has been made on academics.

It sounds like you regret the direction that NIL is taking athletes, that is, away from their education.

They can say, “I can make a million bucks a year doing ads for Gatorade. Why should I go to Econ class?” And they may be right. After all, Bill Gates dropped out because he thought he had a better path. But for most people, staying in school and getting a degree is a good thing for the rest of their life.

Yet some still are leaving school early to go pro. If you're good enough to go pro, you're going to be tempted, but only a few are that good.

Some people have said that NIL cuts the other way on that. And I think we're seeing some evidence of that as well. If someone is making $100,000 on the side in college, why do they need to go pro? They might as well stick around, get an education, and collect money while they can. There may be a hidden benefit: NIL is making staying in school longer more attractive.

But it also puts money more squarely in the middle of everybody's aspirations.