There is a certain timelessness to the sensory experience of the Reading Room: the scratching and shuffling of paperwork, the muffled thump of a closing book, the dull hum of fans in the warmer months. But in recent years, something decidedly more modern has joined in the chorus: the quiet staccato of laptop keyboards.

The emergence of computers and the internet has reshaped nearly every aspect of how libraries operate. At the same time, trends in legal education and the profession have led to changes in collections management, research-based curriculum, scholarship, the student experience, and other aspects of how law libraries support their institutions and the public more broadly.

In the following article, Law Quadrangle speaks with three directors of Michigan Law’s library—representing more than eight decades of cumulative service to the Law School and its faculty and students—as well as alumni who have served in leadership roles at the law libraries at Boston University and the University of Notre Dame, to discuss these trends; their impact on students, faculty, and society; and the enduring value of law libraries.

The arrival of digital databases

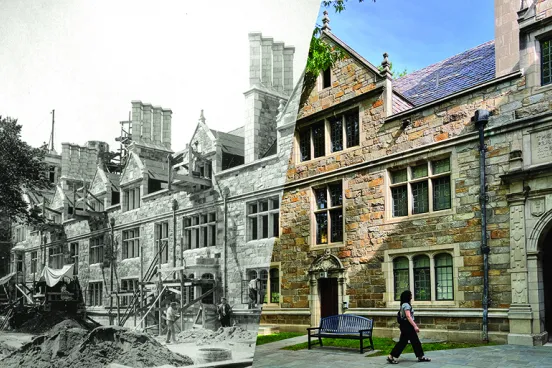

Academic law libraries are in constant motion, adapting to the times and to the evolving needs of the law schools they support. Michigan Law’s library has seen many iterations since it was first housed in the Law Department building at the northwest corner of what is now the Diag. It later moved to the Law Quad in 1931, and its growing demand for space eventually led to the library’s underground expansion that opened 50 years later.

In recent history, one trend has most profoundly affected law libraries and legal research: the increasing availability of online information. Decades before smartphones became handheld gateways to the internet, developments in computer technology had already begun to reshape nearly every aspect of how libraries operate.

One of the first signs of major change was the arrival of early computer terminals dedicated to legal research at academic and legal institutions in the late 1970s.

“Law librarians were very affected by the development of Lexis and Westlaw because almost from the very beginning, they became a place where we could do a lot of our research,” says Margaret Leary, director of Michigan Law’s library from 1984 to 2011. “It took some time for them to build their databases backwards, but by providing statutes and case law they offered most of the primary material that we had to work with. Then they fairly quickly added secondary material and became as current as anything we could get in paper.”

Barbara Garavaglia, ’80, who worked in the Law Library for 32 years, succeeded Leary as the Law Library’s director in 2011 until her retirement in 2020. She recalls that few computer terminals were available in the early days of digital databases, and it was a very different experience from using an online resource today: There was only one computer when she was a student at Michigan Law—a dedicated Lexis terminal—and each student was limited to 30 minutes of use per year.

As the research environment began to migrate from the physical realm to be at least partially digital, collections development became more focused on acquiring access to digital databases with content curated by publishers, rather than a traditional approach to collection building managed in-house on a title-by-title basis. And while some digital resources proved their value from the beginning, library leadership had to regularly evaluate the cost and effectiveness of different digital products as they were developed.

Garavaglia recalls meeting with Leary to discuss CD-ROMs, which some libraries had started to buy and incorporate into their collections in the early days of electronic resources.

“The different CDs had different software, and updating and maintaining them involved a lot of rigmarole. Many of them weren’t even very robust compared to the full text and Boolean search capabilities of Lexis and Westlaw,” Garavaglia says. “So we didn’t invest very much in CDs because we thought something better would come around.”

As digital technology evolved and widely available consumer-facing tools like Google augmented expensive institutional databases, these technologies connected the user to troves of freely available information online—some of it reliable, more of it less so.

This development has required librarians to regularly navigate the large amount of incorrect or outdated information online to find and vet potentially valuable sources of information. This vetting process means that when someone finds an external electronic resource via the Law School’s library catalog—such as the Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse, a public, online repository run by Michigan Law Professor Margo Schlanger—library staff has deemed the information to be trustworthy.

“Historically, legal research skills were learned within a print collection curated by librarians who ensured the substantive reliability and quality of the books, and building and maintaining that physical collection was a structured endeavor requiring expertise, knowledge of the law and legal systems, and how to conduct effective research,” Garavaglia says. “A library collection is an intellectual space, and today the collections that are a mix of print and electronic holdings are just as curated as the print was. While formats continue to evolve and change, the substantive expertise of librarians and the sophisticated work of curation and management remain critical.”

Changing collections, changing staff

The increasing adoption of digital collections also required the library to rethink its staffing and the different responsibilities that came with online databases versus print collections. “We had a staff that was used to processing print items, and that switchover was kind of threatening because many people weren’t going to be needed anymore,” Garavaglia says. “So there was a lot of change in the type of staff that we have had over the years.”

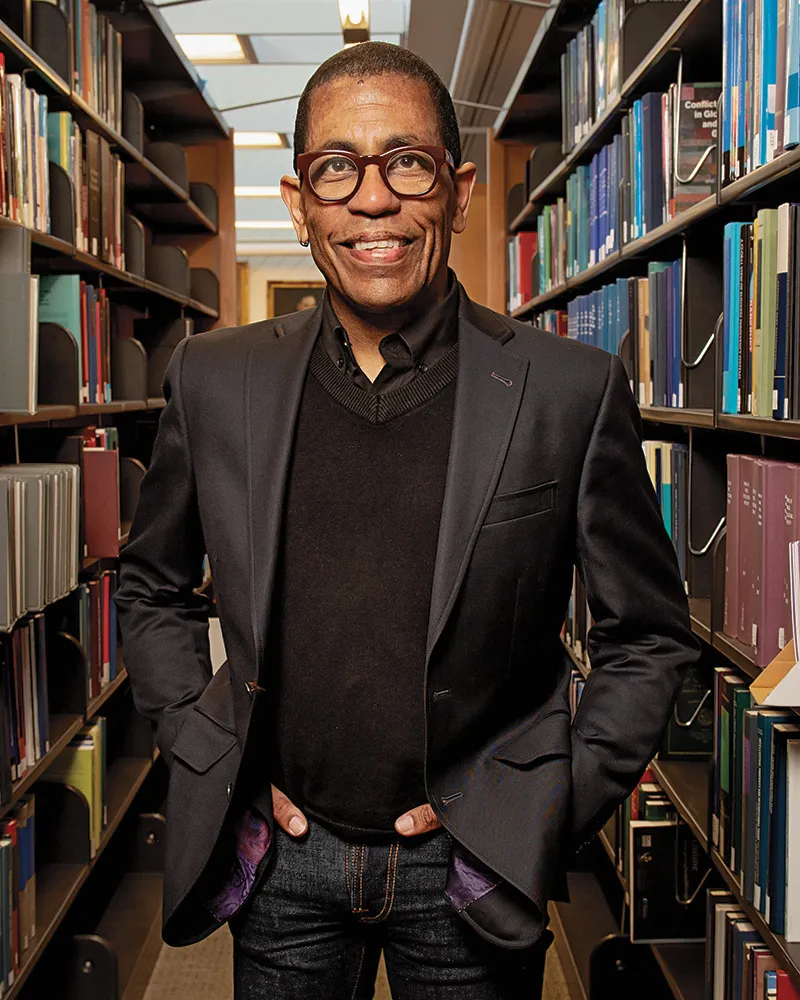

Kincaid Brown, ’96, who has worked in the Law Library for 26 years and succeeded Garavaglia as its director in 2020, says this trend has echoed throughout his tenure at the Law School.

“We used to get 10,000 items a month, and that isn’t the case anymore. So overall, we have fewer people who deal with processing materials and getting them to the shelves,” Brown says. “But at the same time, we have more people who deal with public and research services, because libraries have become much more of a service point for legal scholars and members of the public. We have added more public service librarians who provide these services. Our focus is still faculty and students, but we also field all sorts of questions and requests from people all over the world.”

Another change has been the introduction of tasks for library staff that simply didn’t exist in the predigital era. Ronald Wheeler, ’90, associate dean of Boston University’s Fineman & Pappas Law Libraries and associate professor of law and legal research, oversees a team entirely dedicated to managing the library’s electronic resources.

“It takes a village to manage all of this electronic information, and we have a robust technical services team,” says Wheeler. “They are constantly fixing online links and troubleshooting problems with vendors when certain databases aren’t working. And then there’s the issue of data security. Some people say, ‘Who needs librarians now that it’s all online?’ Well, we keep things online, secure, and running, and we make sure the right people have access.”

An evolving faculty focus

The increasing availability of online research materials has made it easier for scholars to access information that would have previously required a librarian to locate a print resource. At Michigan, Brown says this has led to changes in the complexity of the faculty research queries that the staff takes on—and to the composition of the library staff.

“On the one hand is document delivery, and the requests have gone down just because so much more is easily available to the faculty or students themselves—they don’t even have to get out of their chair to get it,” Brown says. “But on the research side, we still receive an interesting gamut of requests: literature reviews, accumulations of case law on a particular subject, 50-state surveys, or gathering foreign legal materials for comparative research projects. The overall volume of requests has decreased, but the average research project tends to be more complicated.”

Dwight King, ’80, emeritus associate director for research and instruction at the University of Notre Dame’s Kresge Law Library, has witnessed similar trends.

“More recent faculty came in with greater research demands, and the research became more involved,” he says. “That has been particularly true for people pursuing things like interdisciplinary and empirical research, as well as international law research.”

Empiricism has become a focus for a number of faculty at Michigan Law—so much so that the library has added two full-time staff dedicated to the discipline. German Marquez Alcala, who joined the library in 2019 as its first research associate for empirical legal studies, sees value in having dedicated staff to assist with data analysis and related empirical work.

“Most student research assistants can only work with a faculty member for a semester or two, and that’s often not long enough to wrap up a complex project. We provide a steady place for them to keep engaging,” he says. “There is value in having institutional memory for these kinds of research activities, especially for multiple projects that spring from one large data source or one grant that turns into several distinct projects.”

Marquez Alcala emphasizes the critical role that data can play in assembling a compelling argument, legal or otherwise.

“Empirical research can help us understand the implications of public policy changes so we can move in ways that are evidence-based when theory on its own may not have the answers,” he says. “A good example is a project we worked on with Professor J.J. Prescott related to criminal record expungement in Michigan, which ended up motivating a lot of legislative changes across multiple states. It was really exciting to be a part of that.”

Managing increasingly complex collections

Every library evolves to support the goals of the institution it serves. At Michigan Law’s library—one of the preeminent legal research libraries in the world—Brown says that they may be more focused on continuing to build a print collection than some other institutions.

“Our collection is ultimately a research collection, and that means we need to be mindful of what people are going to need to use in the future—it’s not just about the new stuff,” says Brown. “So we have been reticent about going online-only for a lot of things. We still collect many things in print that smaller libraries, or even some of our peer libraries, canceled a long time ago. And that’s because we think it’s important for things we’re going to want forever. Who knows what tomorrow will bring for the web, but the print will still be here.”

The longevity and preservation of access to print archives is in contrast to many of the licenses that govern the use and access of digital materials. Some licenses may provide some form of perpetual access, but most function on a subscription-based model where cancellation eliminates access to the digital materials.

To complicate matters further, electronic subscriptions tend to be more expensive than their counterparts in print. A few trends are likely driving the costs, Brown says.

“Part of it is that publishers want to stay in business, and so when they price the electronic version, they try to match the print spend. Also, many publishers have been purchased by larger companies that respond to shareholders. And publishers are rightly worried about their disappearing models for selling things and are trying to make money where they can.”

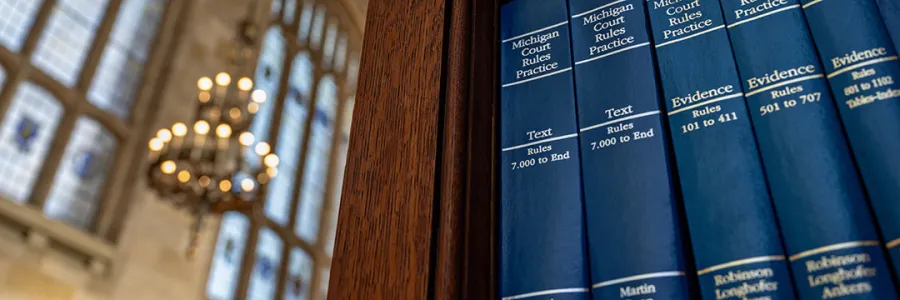

Brown adds that some of the databases justify their costs by doing more than simply replacing the print version and that increasingly advanced search functions and other product features have made certain types of research much more efficient. He points to Lexis and Westlaw as examples.

“You can now search a number of different things that you want together and then filter down to be specific about a particular code section, for example. You can then find commentary about that code as well as secondary sources and regulations related to a specific subsection. That can be done in a matter of minutes, whereas in the old days it might have taken a few hours.”

Michigan Law began to spend more on electronic resources than print for the first time in the 2020s—relatively late compared with similar institutions. Part of that, Brown says, is the Law School’s duty to the state of Michigan as a print repository and archive for state statutes and related materials. But the trend toward electronic materials continues: “The percentage of print has continued to go down precipitously, and that’s not just cancellations—more and more of the print is just not being made,” Brown says.

At Boston University, Wheeler is constantly weighing the print-versus-digital question.

“The first thing we think about is the user. For us, that usually means electronic because that’s what the law firms are using and we want to train our students to use materials the way they will use them in practice,” Wheeler says. “Law firms aren’t buying much in print anymore—it’s expensive and takes up too much real estate. So the percentage of what we purchase in print goes down every year.”

Wheeler says that strategic questions of acquisitions and collections management have shifted for research institutions as space and budget constraints have made it impossible to procure everything for everyone.

“We are going to maintain the research status of our library, and we will continue to build our collection. But the point is access, not ownership. We have other libraries that we partner with here in Boston, and I know other librarians, like Kincaid at Michigan Law. We can get what our people need.”

The importance of preservation

“When the web became more prevalent, there was this assumption that you could throw everything away because someone else would probably digitize it, and then you could use that space for something else,” Garavaglia says. “And I remember thinking, ‘Okay, but isn’t there an obligation to the wider world to ensure that legal information is preserved?’”

There are many good reasons to maintain print archives. Michigan Law has always had a particular emphasis on international law because of the Law School’s historic strength in the field. (The University’s founding charter required the Law Department to hire a faculty member specializing in international law.) This focus on foreign collections has resulted in important historical records being preserved.

“Depending on the country, it is especially important to get things in print because there’s no guarantee that the government’s not going to go away,” Brown says. “When the provisional government of Afghanistan was writing the new laws in the early 2000s, they actually interlibrary loaned their historical legal codes from the Law School because the Taliban had burned all of the copies in the country when they were previously in power. So it’s especially important for countries that are not stable. We have a researcher on the faculty who specializes in Cuban law, and our Cuban law collection is very valuable to that research because a lot of that was destroyed during the revolution.”

It doesn’t take the collapse of a government to impede or lose access to important historical information. Garavaglia recalls a time when the Law Library replaced print records of congressional hearings with a digital product, only to realize later that the process had accidentally created a gap in the collection.

“We put a call out around the country and ended up getting back what we had thrown away, but had we waited a few more years, it wouldn’t have been available,” she says. “And that’s why we always try to avoid wholesale throwing things away when making a migration, because it can be a costly error. It’s really labor intensive to repair it—if you’re even able to do so.”

Leary, who led the Law Library through three decades of significant technological change, emphasizes that the way in which print materials are archived is also important, whether that is digital or microfiche.

“You also have to be careful about how accurately the digital version replicates what was in print,” Leary says. “At one time we noticed there was a microfiche producer in Ann Arbor who would eliminate pages from the front and back of the book that they didn’t think were important in order to make their product more profitable. But if those pages were indexes, then the pages really did matter. And even knowing what kind of advertising, for example, was in certain types of publications is useful depending on what you’re researching. So it is very important to be careful when making those decisions.”

More emphasis on students

For most of the 20th century, law libraries tended to be more focused on supporting faculty research and maintaining their collection than on supporting the student experience and training them in legal research.

“Librarians teach legal research as a discipline now, but that wasn’t the case when I was in law school. Legal research was called Case Club and taught by third years, and it wasn’t always taken seriously,” says Wheeler, who leads the law library at Boston University. “But there has since been an acknowledgement that legal research is a discipline, and an important one. In fact, it’s one of the most important skills that lawyers need to have.”

And while law schools may have traditionally underemphasized the teaching of legal research, that doesn’t mean it wasn’t taught or important to the profession—it was more common for those skills to be developed on the job, leaving law firms or other organizations responsible for the training.

Stefanie Weigmann, ’90, who works alongside Wheeler as associate director for research and instructional services at Boston University, began her career in private practice. She remembers doing a lot of learning on the job.

“When I first got to the firm, they needed tax people, so that’s what I worked on even though I had never taken a tax law class. So of course the first thing the firm did was teach us tax law research,” Weigmann says. “I don’t know if legal research was underappreciated, it’s just that often firms taught you that when you got to the workplace. Now they’re doing less of that because it’s expensive.”

An evolving curriculum

The shift to a more research-based curriculum at law schools has evolved in tandem with legal academia’s increasing emphasis on experiential learning. Weigmann says this has been, at least in part, driven by changing expectations from students as well as what the legal industry expects from graduates.

“I think sometimes students got to their third year of law school and started to wonder what they were still doing there. And so clinics and more robust research and writing classes were part of that development to make the curriculum more varied and to make sure the students were more prepared when they started to practice,” Weigmann says.

In addition to overseeing a team of six librarians, Weigmann teaches in Boston University’s Lawyering Program. The program—which is similar to the Legal Practice Program at Michigan Law—is designed to familiarize first-year students with researching and writing briefs, memos, and other materials they will use in practice. Weigmann and the other librarians teach the research side and partner with a legal writing professor who focuses on the drafting side. That integration is key, Weigmann says.

“When research is a standalone class, a lot of students don’t really see how it fits into their day to day. Most people think about being a lawyer as writing a great brief or talking to a client or arguing in court, without realizing all the work that goes on to get to that place where you know what the legal sources are and how to deploy them,” Weigmann says. “So the more we integrate it, the more students will see the interrelation between the research and the writing and the understanding of the law.”

The profession’s increasing focus on legal research as a discipline can also be seen in the content of the NextGen bar exam, which the National Conference of Bar Examiners is developing. The exam is set to debut in certain jurisdictions in 2026 and will include a section on foundational lawyering skills with an emphasis on legal research and writing, among other topics.

At Boston University, librarians are embedded in the first-year program and continue to teach in the second and third year as well, leading classes like advanced legal research and LLM research. In addition, the library offers a series of lectures on legal research each spring, and students who attend a certain percentage of them receive a university- sanctioned certification for legal research for practice—something they can put on their résumé and use when they enter the job market.

But Wheeler also stresses the value of the library as a point of connection. “My philosophy is that this is a library—no one is carrying around hearts beating on ice. We should work really hard, laugh every day, and enjoy our time here and enjoy our students. Every facet of legal education and educating lawyers can benefit from the expertise of a librarian. I’m always looking for opportunities to strengthen the organization,” Wheeler says. “When I was hired, the dean said to me that she wanted the library to become the center of the student experience. We do a lot of community events to promote that, and students get to learn about what we do in the library while interacting with their professors and having fun. Our approach facilitates relaxed and casual interactions.”

Brown and the staff at Michigan Law’s library have similarly made efforts to bolster research training and to become more central to the student experience.

“As things have migrated online, students think less about coming to the library—and that has, in a way, been a disservice to them,” Brown says. “So a lot of what we do in the library is not only about information literacy, but research literacy because it seems like students aren’t really taught how to research in college as much as they used to. There is so much information out there that it can be hard to know where to start and where to finish and what the steps should be in between. So we do a lot of outreach and a lot more programming to give students bite-size things they can take away to improve their work.”

Training students for the research of tomorrow

Many of the library’s programs at Michigan Law focus on practical skills that would be valuable in the course of students’ education as well as in practice—much of which centers on emerging digital tools and other resources. There is a session about properly redacting digital PDFs, for example, to ensure confidential or otherwise sensitive information isn’t accidentally shared by improper digital redactions. Other subjects include training and best practices related to artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots and other AI tools, as well as an introduction to the different types of digital citation managers that are available and how to properly use them. At Michigan and elsewhere, the focus on AI has grown in recent years.

“I’m teaching legal research this year, and we’re really concentrating on AI. We are emphasizing the Lexis AI product, which is searching curated materials rather than the whole internet,” says King, the emeritus librarian at Notre Dame who has continued to teach during his retirement. “We know AI is part of the future of legal writing and research, and it’s something that will likely help people be more efficient and will become more prevalent. But as with all legal research, you have to verify.”

And while AI remains an emerging technology—and therefore flawed—King says it’s important to embrace new opportunities and not cling to past ways of doing things.

“Over time, I’ve learned not to assume the old way is better,” he says. “When I started in legal research, your ability as a librarian was judged by how well you could use print resources. Then the question became: Could you master commercial electronic resources? Then it was about finding more economical ways of doing research—repositories where you could get reliable information on public websites, for example. And now with AI, it’s about learning how to prompt and verify. It’s always been the case of asking databases the right questions but over time using new technologies.”

And while formats and research methods may change with the times, the enduring value of law libraries and the support they provide remains clear—whether that’s ensuring easy access to online information or helping someone dig up a dusty tome from deep in the stacks.

“Because of the political power of the publishers and copyright holders, it’s very clear to me that if libraries didn’t already exist, it would be a really hard sell to start the first library now. But libraries are a public good that supports everybody. That’s especially true of public libraries, and it’s the value of Michigan’s Law Library as well,” Brown says. “It’s the preservation of the materials that you’re not going to be able to get ever again. It’s a safe service point for students who come from all sorts of different backgrounds to ask for help in a nonjudgmental space. And one thing that hasn’t changed over time is that librarians want to help. That’s what we’re here for.”