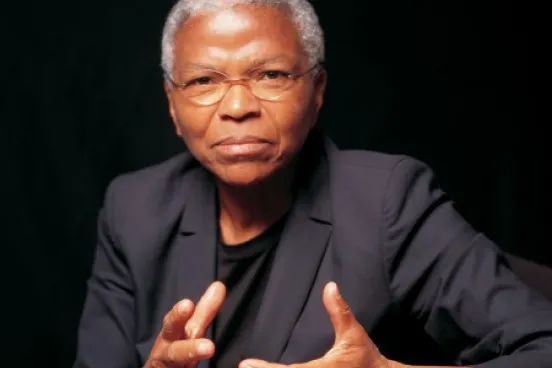

Denise Brogan-Kator, ‘06, fought in the trenches in the battle for marriage equality, planning and editing amicus briefs that would help get section three of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) overturned in 2013, and that later helped influence the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2014 landmark Obergefell v. Hodges ruling in favor of same-sex marriage.

But she soon realized that those victories unleashed a different set of problems altogether.

“When marriage equality started happening around the country, we started recognizing that family laws in the states were written in gendered terms like husband and wife, or mother and father,” she says.

For example, hospital forms for new parents asked for the names of the mother and father, and would now exclude legally married same-sex parents.

So Brogan-Kator, the state policy director for Family Equality Council, a national family rights organization, hit the road to speak to governors, attorneys general, and departments of health around the country, to impress the importance of gender-neutral language.

“If it says husband and wife, interpret it to say spouse. If it says mother and father, interpret it to say parent. Then we’ll have the spirit and letter of the Supreme Court decision,” she says.

The result of her work was overwhelmingly effective.

“Many states have seen the logic and have changed policies accordingly,” Brogan-Kator says. And even those that didn’t, like Florida, have been successfully sued.

It’s just one victory in Brogan-Kator’s storied legal career, which began when she graduated from Michigan Law at age 51. She was inspired to go to law school after losing two jobs because of her transgender identity, which she acknowledged in 1993. The Navy veteran then lost her home and declared bankruptcy. When her children’s mother divorced her, her parental rights were threatened for no reason other than the fact that she was transgender.

She was the first openly transgender student to matriculate at the Law School, and later would be the first openly transgender professor when she was a lecturer here in 2013. She was an integral part of the successful effort to get the University of Michigan to adopt new bylaws protecting transgender people from discrimination in employment, financial aid, student registration, and more.

In law school, Brogan-Kator met her now wife, Mary Kator, ’84, on Match.com.

After graduation, the pair started a law firm together in Michigan that served the LGBT community. Brogan-Kator was the chairperson of the board for the Triangle Foundation, which later became Equality Michigan. She then served as that organization’s executive director before going to work for the Family Equality Council.

In her current role, Brogan-Kator is focused on “taking the mission of the Family Equality Council to the state level.”

She does that through policy—“working with elected officials to try and get them to either interpret or pass law in a way that is fair to LGBT-headed families”—or through programs across the country that give LGBT families “access to a lawyer and to fundamental family protections for free.”

Many of the families with the most need for such services are in the rural South, where Brogan-Kator cites another recent victory. Mississippi was the last state in the nation that banned gay couples from adoption. Brogan-Kator and the Family Equality Council helped sue to get the ban lifted in April 2016.

“Now, there is no place left in the country where a gay couple or individual can’t legally adopt,” Brogan-Kator says.

Now 61, Brogan-Kator has two grandchildren, impactful work, and no small measure of happiness.

“I nearly lost everything I valued in life,” she wrote recently in a New York Times editorial on transgender stories. “But, in the end, I found myself.”