On the first day of spring, Jeff Titus took a walk in the woods.

It was only fitting: Nature has always been his haven. But the walk on this brilliant, sunny day—albeit with a nip of winter wind still in the air—was different. As sandhill cranes bugled in the distance, he pointed to an incongruous pile on the ground. It was hair—his hair—from when he recently found a spot among the trees to shave his head and long beard after being released from prison. He left it there so birds can use it to build nests.

This is Titus’s first spring in the woods in more than two decades.

Titus, a Michigan Innocence Clinic client, was exonerated and released from prison in February. He was convicted in 2002 of killing two deer hunters in a state game area in the southeast corner of Kalamazoo County, Michigan.

The case garnered nationwide attention when two programs shed doubt on his conviction: the 2020 documentary Killer in Question by Jacinda Davis and the Undisclosed podcast by Susan Simpson.

The Innocence Clinic became involved in 2012 when two Kalamazoo County sheriff's deputies, Roy Ballett and Bruce Wiersema, called to say that the wrong man was in prison for the crime and they knew that to be true because they had cleared him.

“That’s a call you just have to follow up on. So we did,” says David Moran, ’91, clinical professor of law and co-founder of the Michigan Innocence Clinic.

A Cold Case Heats Up

Around 5 p.m. on November 17, 1990, Doug Estes and Jim Bennett were found dead a few feet apart with shotgun wounds to the back in the Fulton State Game Area. The wounds were inflicted with different types of shotgun ammunition.

Titus immediately came under suspicion because he had a farm adjacent to the part of the game area where the bodies were found, and he had a history of confronting hunters who had strayed across the property line onto his farm. But the original police investigators, Wiersema and Ballett, cleared Titus because he, too, was hunting that day—27 miles away. Titus's hunting partner and the elderly couple who owned the land where he hunted all confirmed that Titus and his partner did not leave until around 6 p.m. After Titus came home and spoke with the police around his property, he went next door around 8 p.m. to talk to his neighbors.

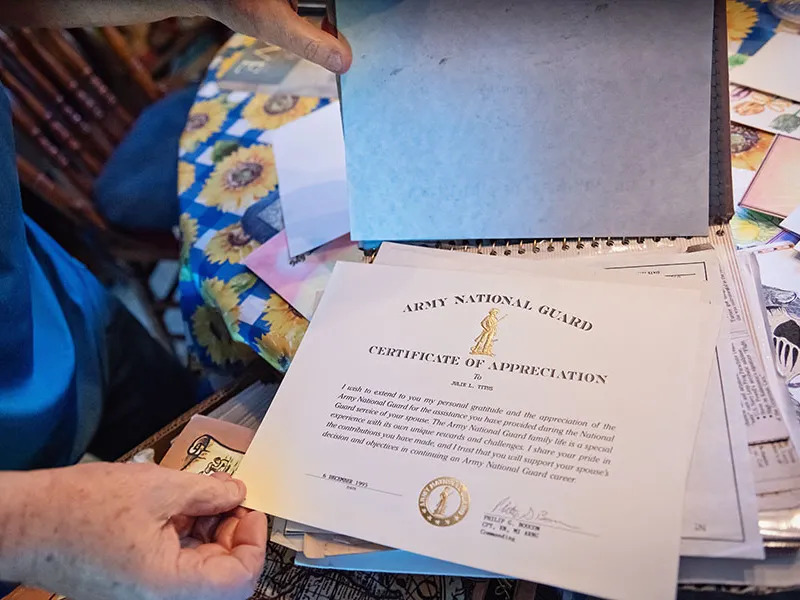

After several years of investigation, the case went cold, until a team reopened the case in 2000. They decided that Titus—a former military police officer who guarded Vietnamese refugees during the evacuation of Saigon and served on President Nixon’s security detail—was the killer and arrested him.

“When Jeff went on trial in 2002, the prosecution’s theory was—and I’m not making this up—that Jeff, while hunting 27 miles away from the game area, suddenly began to worry that some hunters in the game area might trespass on his land. So he sneaked away from his blind, drove home, found two hunters too close to his land, killed them, and then drove back to pick up his hunting partner,” Moran says.

By the time the cold case team reopened the case 10 years after the killings, the elderly man on whose farm Titus had hunted had dementia, and his hunting partner had serious memory lapses. At the same time, his neighbor testified that Titus had come over to discuss the killings earlier than originally stated, which would put Titus in the area at the time the bodies were found. In addition, Titus’s coworkers testified that he talked a lot about the killings at work, albeit without implicating himself.

At trial, several people testified that shortly after the hunters were murdered, they saw a man who had driven a small car into a ditch near the game area. The man appeared sweaty and nervous and refused offers to help get his car out of the ditch.

“The defense at trial pointed to the ‘ditch guy’ as the real killer, but to no avail,” Moran says. Despite Titus’s alibi and the unexplained presence of a person acting strangely in the area at the time of the murders, Titus was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without parole.

The Innocence Clinic gets involved

When the Innocence Clinic took Titus’s case, they first litigated ineffective assistance claims centering on trial counsel’s failure to interview the police investigators who had cleared Titus. The trial court rejected the claims on the ground that anything the original officers had learned would have been excluded on hearsay grounds.

The clinic next began litigating the case on federal habeas. As a student-attorney, Alejandro Montenegro, ’15, worked with his clinic partner, Rebecca Eisenbrey, ’15, on the petition.

“Since Jeff's wrongful conviction was brought to the clinic’s attention by the detectives who originally investigated the double homicide, the case was a perplexing outlier,” Montenegro says. “There were still many unanswered questions.”

He and Eisenbrey were responsible for reexamining case files from the trial, walking through the crime scene, interviewing witnesses, and interviewing Titus. Ultimately, he and Eisenbrey helped write and file Titus’s habeas petition.

Alejandro Montenegro, ’15“Working on Jeff’s case really illustrated how our legal system is unjustly tilted against defendants”

The “Ditch Guy”

In 2019, documentarian Jacinda Davis and podcaster Susan Simpson started investigating. They soon discovered that a serial killer named Thomas Dillon had been arrested in 1993 for a series of murders of hunters and outdoorsmen in Ohio. Dillon pled guilty to five murders to avoid the death penalty, but he was suspected in several more, including in other states.

And then they found something truly remarkable.

Davis and Simpson discovered that in 1993, authorities in Ohio contacted the Kalamazoo County sheriff, who brought to Ohio two of the witnesses who had seen the man whose car was stuck in a ditch the night of the Fulton State Game Area murders. The witnesses both identified Dillon as the “ditch guy” in live lineups. In addition, one of the witnesses had produced a sketch back in 1990 of the person she’d seen that night—and it was spot-on for Dillon. She also had described the car, which matched the one belonging to Dillon’s wife.

Digging deeper, Davis and Simpson learned that Dillon had killed a hunter the week before the Kalamazoo-area killings and another one the week after and that he had borrowed two shotguns from coworkers the day before those killings. (The hunters whom Titus was convicted of murdering had been killed by different kinds of shotgun ammunition.) In addition, a man who was incarcerated with Dillon told the FBI that Dillon had bragged about an occasion when he killed two hunters at once.

It Doesn’t Add Up

Despite all of that evidence, the sheriff had dismissed Dillon as a suspect in the killings near Titus’s property. The reason: The office made a simple math error as to whether or not Dillon could have driven to Michigan in time to commit the murders. He could have.

Because of that error, when the cold case team reopened the case in 2000, Dillon was not considered a suspect and nothing about him was disclosed to the defense. The possible presence of a serial killer in the area never came up at Titus’s trial.

The Innocence Clinic brought Titus’s case—with this new information—to the Michigan Attorney General’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) in 2020. Dillon had died in prison in 2011.

Alexis Franks, ’23, a student-attorney in the Innocence Clinic, was the primary liaison with the CIU this past year, coordinating video calls between the CIU and Titus. She also received weekly updates from the CIU’s director and provided the director with any documents or evidence she needed as questions arose.

Franks also spoke with Titus weekly and encouraged him to remain hopeful, even though progress was slow. In those moments, she was speaking to herself, as well.

“To be honest, I tried not to get my hopes up. There are so many obstacles that can arise before someone is officially exonerated,” Franks says.

Titus recalls that Franks, along with her fellow student-attorneys working on his case, Naomi Farahan and Olivia Daniels, had promised that all three of them would call him when there was good news. So as much as he loved talking with Franks, a part of his heart sank any time it was just her on the phone.

Still, “Her voice always uplifted me,” Titus says. “She was my lifeline to the outside world.”

On February 16, the day after Titus’s 71st birthday, Franks, Farahan, and Daniels finally got to make the conference call that they had long hoped to make: The CIU had stipulated to unconditional habeas relief on the grounds that evidence favorable to Titus’s defense had been withheld from his legal team.

“Alexis said, ‘Jeff, I’ve got Olivia and Naomi here on the phone with me,’ and I just started bawling,” Titus says.

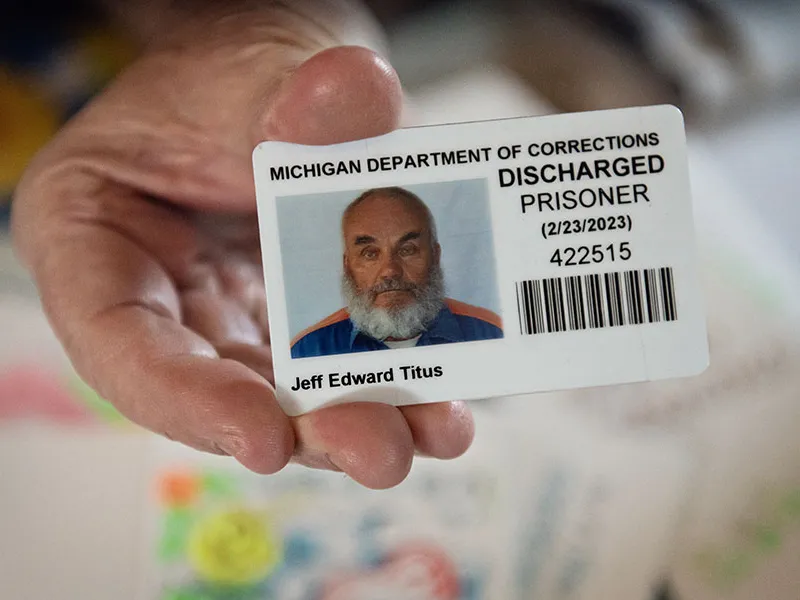

After being held for 21 years, Titus was released from prison.

Franks, who wasn’t able to be there on the day he was released, recalls, “When I FaceTimed Jeff, I cried with joy.”

In Chicago, Montenegro—who worked on the habeas petition and is now an associate at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP—texted his clinic partner, Eisenbrey, and sent an email to Moran.

Then “I screamed a few celebratory expletives.”

Alexis Franks, ’23“To be honest, I tried not to get my hopes up. There are so many obstacles that can arise before someone is officially exonerated”

“I Can’t Let It Eat Me”

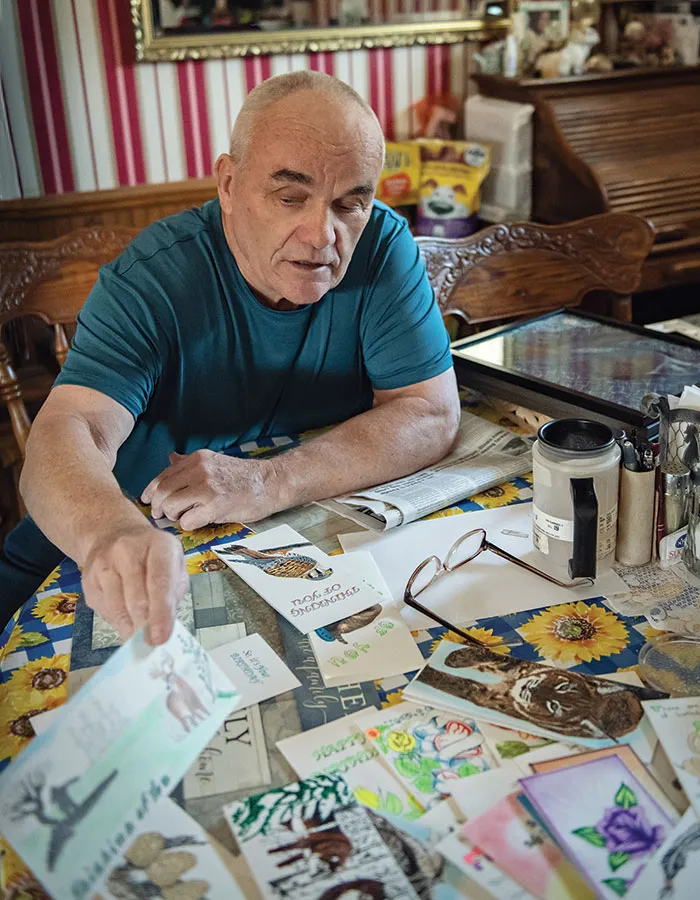

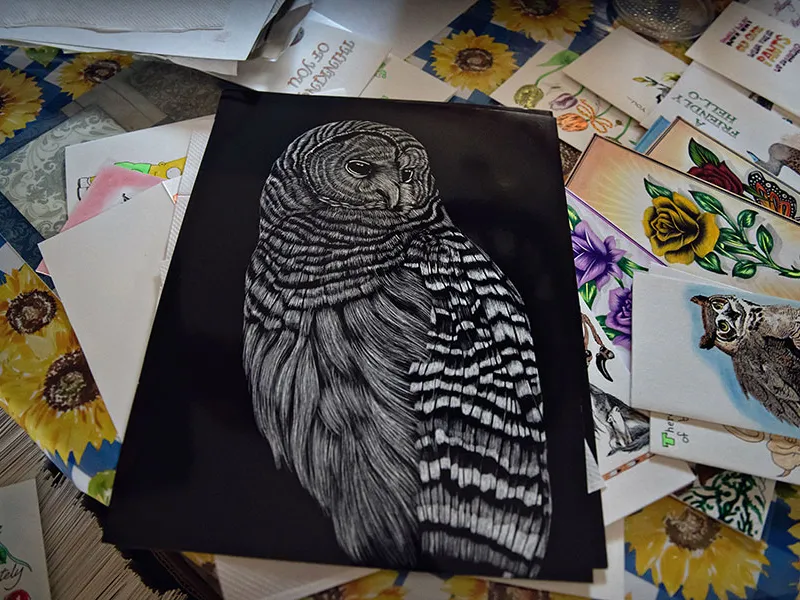

On June 1, Kalamazoo County Prosecutor Jeff Getting announced he is dropping all charges against Titus. He will not face a new trial. As Titus figures out what’s next, he is determined to enjoy life. In prison, he began creating greeting cards; he estimates he has made about 20,000. He has boxes and boxes of them—some are sentimental, some are humorous. Many depict wildlife from the woods he loves. His buddy in prison also is an artist; they plan to go into business together when he gets out.

Titus shows his former-Marine stoicism when he talks about the sequence of events that led to his conviction and about his time in prison. “I can’t let it eat me,” he says. His voice cracks with emotion, though, when he talks about his team of student-attorneys. “My students, they mean the world to me. I just want them to be blessed.”

Moran praises the 36 student-attorneys who worked on Titus’s case over the span of more than a decade, but he calls Bruce Wiersema and Roy Ballett, the original investigators who first alerted Moran to the inconsistencies in Titus’s conviction, “the true heroes in this case.” While Ballett died in 2022, his two sons, Jim and Dan, held their dad’s police badge as they watched Titus walk out of prison.

And then there’s the investigative reporters, Davis and Simpson. They were there on the day Titus walked out of prison, too, and hugged him tightly.

“They had an unquenchable thirst for truth and justice,” Moran says. “I could not be more grateful for the work they did to set Jeff free.”

For the student-attorneys, their work on Titus’s case is much more than a resume talking point. It’s a person whose freedom they couldn’t wait to celebrate with him and whose artwork sits on their desks. One whose story and warm smile has stuck with them over the years—as has what they’ve learned along the way.

“There are too many lessons from my experience to count, but something that always stuck with me is how scary it must have been for Jeff and our other clients to trust us with their lives,” says Montenegro. “There is immense responsibility that goes along with that trust, and I won't forget that.”

Jeff Titus visits with family and members of the Michigan Innocence Clinic at his cousin's home.

Jeff Titus visits with family and members of the Michigan Innocence Clinic at his cousin's home.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus became a prolific creator of drawings and greeting cards while in prison.

Jeff Titus shows a Michigan Department of Corrections ID card that identifies him as a discharged prisoner.

Jeff Titus shows a Michigan Department of Corrections ID card that identifies him as a discharged prisoner.

Jeff Titus's Certificate of Appreciation from the Army National Guard.

Jeff Titus's Certificate of Appreciation from the Army National Guard.

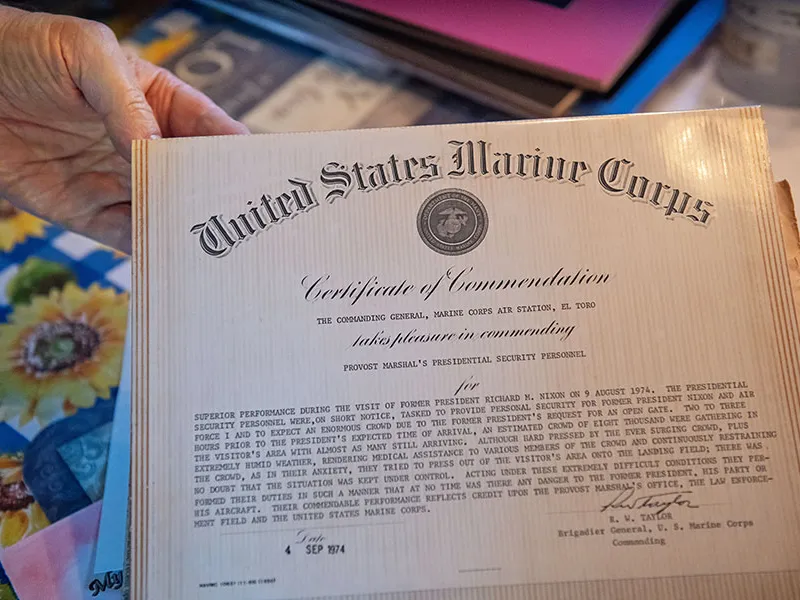

Jeff Titus's Certificate of Commendation from the US Marine Corps

Jeff Titus's Certificate of Commendation from the US Marine Corps