A lawyer’s job is to present a client’s case with a compelling argument, so it seems logical that U-M’s undergraduate debate team has proven to be fertile ground for future Michigan Law students. But set aside your notion of classic courtroom oration in one important way when you consider the intricacies of college debate: If lawyers have to think on their feet, debaters do it at hyper speed, like these double Wolverines.

Top debaters can reach more than 500 words per minute, and speaking as quickly and clearly as possible— or “spreading” as they call it in debate jargon—is necessary to make all points in the time allotted. “The only downside to my debate background is that I when I became a professor, I had to learn to slow down my speech,” laughs Robert Hirshon, ’73, the Frank G. Millard Professor of Law at Michigan Law, “because my students couldn’t follow me.”

Michigan’s debate team was established in 1903, although students have debated at the intercollegiate level as early as 1890. Among the university’s 19 schools and colleges, the Law School claims the most debate alumni—between 35 and 40 percent. U-M Debate Team Director Aaron Kall believes that a common skill set defines the best debaters and the best litigators. “Arguing effectively while anticipating your opponent’s line of defense is critical as there is little time to prepare rebuttals. You need to speak as quickly and clearly as possible. Most important, though—you have to want to win.”

Hirshon, who debated in high school and as an undergrad at U-M, agrees it’s no coincidence that former debaters go into law, citing how his debate background enhanced his career as an attorney, as president of the American Bar Association— often as its spokesperson—and now as that slower- talking professor. “Debate taught me superior communication skills and how to frame an argument, and likely played into my decision to become a lawyer. Look, my dad wanted me to be a doctor or a dentist, but I chose law.”

Maria Liu, ’15, also thanks debate for preparing her for life as a lawyer. She was about to enter high school when her mother urged her to attend debate camp instead of spending summer vacation at the mall. Liu quickly became enamored. Joining the U-M Debate Team as a freshman, she was paired with Edmund Zagorin. A powerful combination, Liu and Zagorin were U-M’s top debate team for three years—winning third place at the National Debate Tournament in 2011. Liu vividly remembers the long hours spent practicing and researching to reach that level.

“Reams of printouts and notes that we categorized and stored in heavy 50-pound Rubbermaid bins—one stacked on another—that we wheeled around to competitions. That was the less-glamorous side of it,” she says.

Now, Liu is a litigation associate at Jenner & Block, where she represents clients in complex, high-stakes cases. Like Hirshon, she struggles to slow down her speech—the only part of her debate training she has had to unlearn.

“Debate taught me how to approach issues in multiple ways—because nothing is black and white. It helped me interpret the law and think more creatively—critical for lawyers. The competitive nature of debate drew me to litigation and prepared me well for my job in and out of the courtroom.”

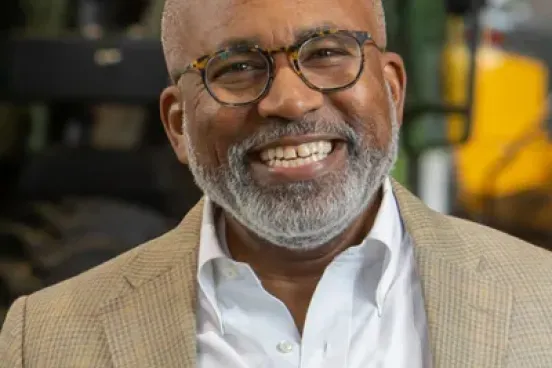

For John Lawson, ’83 (pictured below with students), the tie to debate has proven to be stronger than the tie to the legal profession. He has not practiced law in years but remains co-director of debate at Birmingham Public Schools and assistant forensics coach at Groves High School in suburban Detroit, as well as executive director of the Detroit Urban Debate League. He is the retired chair of the Social Studies Department at Groves.

Still, Lawson sees numerous connections between debate and his time in practice. “Oral arguments before a judge are like debates, from the research you do to how you interpret a case to how you structure your approach. You’re essentially practicing law when debating—drawing a picture for your audience by presenting the evidence you find most credible. It’s incomparable training.”

After debating in college, Lawson turned to coaching and judging—even serving as a judge during the famous debate between Timothy Leary and G. Gordon Liddy at the Michigan Theater in 1982. Much has changed since Lawson debated, with most research being accessible with the click of a laptop button. Lawson recalls standing over a hot copier printing pages from leather-bound volumes—like that documentation Liu remembered towing around in heavy bins. Another change? “The rate of speech is much faster and harder to understand now,” he says.

Like Liu, a parental nudge guided Raj Shah, ’97, toward debate. Now a partner and chair of the Chicago litigation group at DLA Piper, Shah was 13 when his father, a first-generation immigrant, saw debate as a way for his son to master public speaking.

“I agreed to give it a chance but inwardly thought it was nerdy. But once I got into it, I could see it wasn’t nerdy but empowering. My public speaking and advocacy skills strengthened. I mastered the best way to conduct, organize, and strategize research in order to make the best argument—essentially the core of what a good litigator does.”

Shah says preparing for debate is a lot like preparing for court. “You work around the clock thinking of ways to take your case to the next level. No two debates, or cases, are the same. You have to be nimble—think on your feet. No matter how prepared you think you are, something will catch you off-guard. How quickly you recover is what separates winners from losers,” says Shah, who put those skills to use in winning Michigan Law’s 1998 Campbell Moot Court Competition.

These days Shah isn’t involved in debate but sees the experience as an asset in himself and in others. “It’s not a spectator sport, because once you’re not debating regularly, you can’t follow the speakers—they’re too fast. But if I see a resume with debate experience on it, that candidate moves to the top of my list because I know how beneficial those skills are in this field.”