The first thing we do, let’s replace all the lawyers with computers.

While even a modern-day Shakespeare might think such a paraphrase is science fiction, the legal profession is grappling with whether or not it could be true someday. Technology is changing our society in immeasurable ways, and the practice of law is no exception.

At a time when law firms face increased pressure to shake up the old business model, technology enables them to be more efficient and more innovative, and to redefine the value that their lawyers provide. Technology also is working to help diminish barriers that keep many from accessing legal services.

When IBM’s supercomputer, Watson, went head to hard drive with Jeopardy! megachamp Ken Jennings, it was good theater. But when Watson proved it could perform e-discovery tasks substantially faster than human associates, it raised legal eyebrows. A 2015 ABA Journal story reported that only 20 percent of law firm leaders surveyed believe computers won’t replace human practitioners, down from 46 percent in 2011.

So is technology a good thing for the legal profession or a threatening thing? It’s a complex and big question, and one that we can’t fully answer here. But the bottom line is, it is a thing—and in the following pages, you’ll see how Michigan Law alumni are adapting and thriving.

From Quills to Keyboards

Dan Katz, ’05, likens today’s legal profession to the finance industry’s evolution over the last 50 years. “People used to go by hunch when picking stocks,” he says. “Similarly, the law hasn’t been rigorous from a quantitative standpoint. But if you think about what lawyers, especially BigLaw lawyers, are doing, many are solving risk problems, just like finance. And like in finance, the value proposition that humans can bring to legal services is shifting.”

Coincidentally, the upheaval of the finance industry sparked the rapid change in the legal profession, Katz says. “Before the market crashed, you could have an innovation in law, but it was difficult to sell that innovation. Most organizations (clients and firms) weren’t interested in changing the delivery-of-services model, or in finding alternative solutions for the problems to which lawyers have been the solution.”

As an associate professor at Chicago–Kent College of Law and director of its Law Lab, Katz should know. He has been immersed in the legal start-up community for years. Katz is the co-founder and chief strategy officer of LexPredict, a legal analytics consulting and product company that helps lawyers make better decisions using predictive analytics. He also sits on the advisory board for Nextlaw Labs, the legal innovation arm of Dentons. “Historically, if you were on the partner track, you could follow the formula and it worked out,” says Katz. “The legal profession was anomalous, relative to the rest of the economy, in that respect. Now is a much more entrepreneurial time because there are fewer guarantees.”

As corporate clients reevaluated their bottom lines after the Great Recession, many questioned the high hourly rates they were paying to law firms for routine work that could be done cheaper and faster using technology platforms. A 2017 study by the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that 23 percent of a lawyer’s job can be automated, while a widely publicized study by Dana Remus at the University of North Carolina and Frank Levy at MIT said that using all existing legal technology would reduce lawyers’ hours by 13 percent. Others argue that factoring innovations related to people, process, data, and technology together means even greater impact.

Law firms—and their clients—took notice.

“Being a subject matter expert doesn’t hold much weight in our rapidly changing world,” says Jayne Rizzo Reardon, ’83. “You can’t take out your quill and legal pad and think that someone’s going to pay you just because you went to law school.” Reardon is executive director of the Illinois Supreme Court Commission on Professionalism and a proponent of “futurelaw” thinking. “We must quit throwing sand at each other in the sandbox and realize there are very few of us in this sandbox. The game is being played somewhere else.” Under Reardon’s leadership, the commission is examining the future of law, including hosting annual conferences on the topic. The 2017 conference had 490 registrants, up from 270 in 2016. “We are almost past having to set the table with the imperative. Now lawyers are saying, ‘I get that we need to think about these issues; help us figure out how,’” she says.

Reardon’s career began in different times—before the advent of computers, much less the Internet. Still, “I was struck by the inefficiencies,” she says of her high-volume insurance defense practice. “I had 150 cases that fell into a handful of categories. I thought there had to be a systems approach to handling them.” Reardon recalls creating form books to share with fellow associates but says efficiency was not a priority for firms then. “The partners clearly conveyed that the more we drew out a dispute, the more money we made.”

Two decades later, Adam Ziegler, ’02, felt similar frustration as a commercial litigator in Boston. “The more my career progressed, the more I was drawn to questions of efficiency and quality, and the more I saw technology as part of the answer.” Ziegler ultimately left private practice and is managing director of the Harvard Law School Library Innovation Lab. He says his metamorphosis wasn’t born in the midst of a 100-hour workweek, surrounded by boxes of files. “I did high-level advocacy. But every time we appeared in court, both sides ran in place and didn’t get to the heart of the issue. I kept thinking, ‘I care about what lawyers are known for and committed to, but I think our work can be enhanced in ways that are good for clients, for lawyers, and for justice.’”

There’s no question that efficiency now is a priority for firms of all sizes. Client belt-tightening demands it. But Dan Linna, ’04, says the solution is bigger than technology. Linna is Professor of Law in Residence and the director of LegalRnD–The Center for Legal Services Innovation at Michigan State University College of Law. He also will teach Legal Technology and Innovation as an adjunct professor at Michigan Law during the winter 2018 semester. Linna has created a framework and roadmap for innovation, as well as an index that rates law firms on their development of and openness to outside-the-box approaches. “We shouldn’t just rank firms on revenue. We need to shine a light on those who are innovating. It’s good for clients and for lawyers, especially young associates. When you enter practice, you bet your career on the firm you sign with—because you want to make partner there or you want your time there to position you for what comes next. So you want to know that your firm is investing in the future,” Linna says.

He stresses that efficiency stems from innovation. “We, as lawyers, need to be able to tell our clients that we are more than a cost on their bottom lines. We’re not going to use technology-assisted review to lower the cost of diligence; we’re going to use it to do better diligence and more diligence. And we need to show that we’re going to help them avoid billion-dollar mistakes.”

Let’s Run the Numbers

“You can’t just throw technology at problems and get a solution,” says Linna. “You’ve got to understand processes. You’ve got to manage projects. You’ve got to capture metrics and data.”

The staggering increase in data has huge implications for lawyers—if they can harness it. According to IBM, 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created every day, and 90 percent of all data was created within the last two years. Predictive analytics can gauge legal outcomes ranging from the amount of risk in contracts to judges’ rulings. Katz, the professor at Chicago–Kent College of Law, garnered media attention earlier this year when he and his co-authors published a study showing that their algorithm predicted U.S. Supreme Court decisions from 1816 to 2015 with 70 percent accuracy.

Far from just being a cool party trick, the results have real implications for both litigators and transactional lawyers. According to Katz, data—and technology platforms like his startup, LexPredict, which synthesize it—can help companies “de-lawyer” routine transactions, like some contracts. “Lawyers historically would want to review it a bunch of times because they think their job is to reduce risk to zero. But since business is inherently risky, the businessperson might not want to spend money to have a lawyer make micro changes that don’t affect anything. That’s only possible, though, if the business has a data model that supports the belief that this isn’t a particularly risky contract.”

LexPredict’s customized software also can perform early case assessment for clients, to give a sense of a claim’s worth and potential liabilities. “If I’m 7 percent better at predicting outcomes than my competitor at another law firm, it’s not clear that I can win the market because other things like reputation will be factors,” says Katz. “So we target places like a corporate legal department that faces all types of claims. They care about 7 percent.”

The explosion of data also creates opportunities in legal research, says Ziegler, the managing director at Harvard Law Library’s Innovation Lab. “Every time lawyers do analysis or work, everybody should get smarter as a result—whether it’s in the context of our own careers, within our firms or corporate legal departments, or just generally across the profession. There are a lot of examples of crowd-sourced collaboration in fields like software engineering and programming, and it’s time to bring that to the legal profession.” The concept is born in the root of the profession itself, says Ziegler. “The common law system is based on each side presenting a view of the law that reflects well for its client, and a judge considering those inputs and making a decision. Each subsequent case builds on the previous ones, but that iterative nature can take decades and centuries to express itself. I want to combine that with the efficiency of technology so people can share knowledge and analysis quickly.”

In 2013, Ziegler launched Mootus, a collaborative platform for legal analysis and knowledge. He and his co-founder built and launched a prototype, went through a start-up incubator, and, as Ziegler says, “We got quite a bit of interest. But from a business standpoint, it wasn’t there yet.” Ziegler now works with similar ideas at the Harvard Law Library—including an online casebook platform called H2O and the Caselaw Access Project, which is scanning and converting all the court decisions housed at the library into text files, and releasing the files for free online. “It’s expensive to access the law. Even when you can afford to access it, you can’t use it for big data analytics and large-scale research because so much still is only in books or behind other paywalls,” Ziegler says. The Caselaw Access Project is a partnership between Harvard and Ravel, which LexisNexis acquired recently. “Eventually, we’ll push the data into the practitioner world and begin to think about many new possibilities, like what might happen when any law firm can create its own custom online library of cases that are annotated by its lawyers,” says Ziegler.

Lean Lawyering

Getting law firms to heed Linna’s call for improved process and project management, and to embrace analytics, can be tough. One barrier is the investment challenge born of ethical rules prohibiting law firms and lawyers from sharing fees with non-lawyers—an issue that Reardon has been exploring at the Illinois Supreme Court Commission on Professionalism. “The legal profession’s regulations don’t allow lawyers to form joint ventures with technologists, project managers, or other business professionals, so it can be difficult to harness the expertise to build the systems we need,” she says. Reardon recently wrote an article for St. Mary’s Law Journal advocating for alternative business structures that would allow lawyers and non-lawyers to enter into business partnerships. Forty-nine percent of practicing attorneys are solo or small-firm practitioners, Reardon notes, and the demographic’s income has declined 30 percent in the past 25 years. “Inefficiencies are costing lawyers their livelihoods,” she says. “How do we get around those inefficiencies? We have to bring technology into law firms.”

With upper-management’s buy-in and the cushion of a bigger revenue base, some large firms have begun making substantial inroads toward disrupting their business model. Among the lead pack has been Seyfarth Shaw LLP, an AmLaw 100 firm based in Chicago. In 2008, the firm launched SeyfarthLean Consulting LLC, a spinoff firm dedicated to helping clients to drive efficiencies in the practice of law and improve performance. Seyfarth Shaw recently received the 2017 Innovative Law Firm of the Year Award from the International Legal Technology Association for two advances in the use of robotics software with SeyfarthLean Consulting: deployment of robotic process automation software in the legal industry for the first time, and development of the “Ask Lee” chatbot for the firm’s client collaboration platform. The firm also won the award in 2013.

“Technology has revolutionized my practice,” says Julia Sutherland, ’04, a partner in the firm’s international department currently working in London. She specializes in international trademark law, handling clearance matters and managing disputes worldwide. Sutherland joined the firm in 2007, just as the global economy began its slide. Seyfarth was led then by J. Stephen Poor, who wanted the firm to rethink its billable-hour model and explore ways to deliver client services more efficiently. Poor championed the rollout of alternative fee arrangements and embraced Six Sigma, a data-driven approach to streamlining processes. Sutherland’s intellectual property group was part of the pilot, in part because of its acquisition of groups of lawyers from different firms, each of which had their own methods for handling internal processes such as mail flow and docketing. “Managing mail flow and docketing are crucial to a robust trademark practice,” says Sutherland. “Information needs to get to docketing, the correct deadlines need to be entered, and mail needs to go to the attorneys immediately so that they can get ahead of the deadlines. For it to work effectively, everyone needs to be on the same page.”

As the only trademark associate in the Chicago office and manager of the Chicago office’s trademark docket, Sutherland represented her practice group in the pilot. Seyfarth’s implementation of Six Sigma principles to increase its own effectiveness garnered a lot of press, especially given the economic climate. Clients and potential clients asked the firm to help them do likewise. SeyfarthLean Consulting LLC was born, combining the statistical focus of Six Sigma with more conceptual philosophies on waste reduction in a system called Lean Six Sigma.

One of Sutherland’s biggest trademark clients, Wolverine Worldwide Inc., hired Seyfarth Shaw because of its application of Lean Six Sigma principles to the management and enforcement of global trademark portfolios. Sutherland and Jay Myers, a trademark partner in Seyfarth’s Atlanta office, were part of the team that spoke with Ken Grady, Wolverine Worldwide Inc.’s then general counsel and an outspoken legal futurist, to ink the deal. A big selling point was the technology that Sutherland, Myers, and Seyfarth Shaw’s project managers had developed to manage large volumes of trademark clearance, filings, and disputes around the world. They created seven process maps for trademark work, such as filing applications and taking down websites selling counterfeit products. “He loved that we were thinking about these issues and using this technology,” says Sutherland of Grady, who later became CEO of SeyfarthLean.

Wolverine Worldwide Inc. became the first large, global trademark client for which Seyfarth customized a portal grounded in Lean Six Sigma principles. The portal, now called SeyfarthLink, allows the client and the firm to monitor deadlines, track projects (including strategic and high-level projects that are not captured by current docketing software), and warehouse data concerning enforcement successes and failures. The portal also consolidates data so that Seyfarth lawyers and paralegals don’t have to keep asking clients to provide information for a new matter that the client provided for similar matters previously—a win-win under Seyfarth’s fixed-fee structure. “Under the billable-hour model, attorneys are incentivized to go to clients repeatedly for the same information,” says Sutherland, who, with her team, could be handling as many as 220 active matters for Wolverine Worldwide Inc. alone at any given time. “By keeping a document repository—a data room—of everything related to every trademark dispute around the world, a technological solution is addressing a proven pain point for our clients.”

For another client, United Health Group Inc. (UHG), Seyfarth developed a clearance intake tool powered by artificial intelligence (AI) to communicate clearly and directly with UHG’s lawyers and internal business contacts on the risks associated with 80-some new product and services names that UHG launches, on average, each month. “Under the old system, a lot of paper went along a lot of different touch points. It was ripe for the development of client-facing technology,” Sutherland says.

Sutherland, Myers, and the firm’s project managers also developed the Watch App, which allows Seyfarth lawyers and their clients to monitor applications for potentially conflicting trademarks around the world and quickly and efficiently make decisions about whether to challenge them. Previously, the firm subscribed to a weekly paper service that listed global trademark filings. The firm scanned the PDF, sent it to clients for review, and clients advised the firm if any filings piqued their interest. “Ken [Grady, Worldwide’s GC] hated this process,” says Sutherland. “He wanted something he could view on his iPhone at his kids’ soccer practice, something that with the press of a button could start a series of steps. So we built it. Much of our way of thinking involves listening to clients and collaborating with them on technological improvements to reduce their everyday pain points.”

Sutherland, Myers, and their team were recognized for their innovative application of technology to the practice of trademark law, including the development of the Watch App, in the Financial Times U.S. Innovative Lawyers Report 2012. Seyfarth also was named as an industry standout—the highest award given by the publication. Sutherland says the rise of artificial intelligence and technology has enabled Seyfarth to further customize tools for clients, including providing access to real-time spend data, and to increase productivity in the organization.

“Technology has freed me to focus on more complex matters,” says Sutherland. “Even in a commodity-driven practice like trademark law, there’s a huge strategic aspect that is not driven by reducing efficiencies. You’re always going to need a lawyer to give a legal opinion.” Ziegler, at Harvard, agrees. “It might chill the spines of my fellow lawyers, but some activities essential to good lawyering can be done better by computers, and therefore they should be. Lawyers are at their best when they can translate substantive knowledge or situational experience into human terms—when we can provide protection, advice, and peace of mind.”

Technology also is making major inroads in litigation practices, including at Goodwin, where David Hobbie, ’97, is a director of knowledge management. A former litigator, Hobbie became intrigued in the then nascent field of knowledge management (KM). In 2005, Goodwin hired him as the first full-time litigation knowledge manager in the Boston area, although the firm had dabbled in the field as early as the 1990s. “They saw legal knowledge management as a key aspect of their competitive advantage and something they needed to do to provide better client service,” Hobbie says of Goodwin’s leadership, “even in the pre-recession era when the legal market did not provide a huge emphasis on efficiency.”

Hobbie’s role is crucial to the firm’s ability to demonstrate value to clients because he helps litigators access previous work products more efficiently and effectively and organize information about their matters and their people. “My overall goal is to help attorneys access the collective wisdom of our firm better so that they can practice law better.” With 10 offices and more than 1,000 lawyers, it is impossible for lawyers at a firm like Goodwin to maximize efficiencies on their own, Hobbie says. “You can’t know that many people, and you can’t know what everybody is doing, so knowledge management provides tools to help get the right information and connect with the right people. Then we work on tools that enable the attorneys do their work better, which might be a drafting tool, a document assembly program, or an artificial intelligence engine that helps attorneys perform due diligence more effectively, analyze contracts, and so on.”

For a firm like Goodwin, whose client roster includes many startups, Hobbie’s work—and that of his business-law KM colleagues—also enables lawyers to speak their clients’ language more fluently. “Some of our clients are living and even driving technological changes, and to the extent that we’re representing them, we have to understand that so we can bring the best tools to bear to solve their problems.”

In addition to being a constant presence at practice group meetings and training sessions, he seeks endorsements from key leaders. “I can say it’s the greatest tool ever, but that’s my job. If the practice leader or the business leader says the same thing, it carries more weight.”

Hobbie, who is co-chair of the International Legal Technology Association’s 2018 and 2019 ILTACON conferences, also works with Goodwin’s practice management and business development/marketing teams to aid in his firm’s rainmaking efforts. For instance, through his business intelligence tool Goodwin Litigation Intelligence, an online visualization database recognized by the Financial Times, Goodwin lawyers can identify appearances by the firm in all U.S. courts—searching by type of work, class action, and status—and see the firm’s work history and outcome on each case. They then can use the data to convince prospective clients of the firm’s ability to meet their needs.

“There are huge opportunities in working with financial and experience data to help us better estimate what the outcome might be and how much it might cost. It allows us to be more transparent with our clients,” Hobbie says.

Amid the opportunities, however, Hobbie says another important part of his job is to ensure that the firm’s knowledge management path remains on solid ground, instead of just jumping onto the next technological bandwagon. “I see myself as a buffer and a filter for the changes that are happening in legal technology, and I try to mediate them so that I can provide the best, most relevant services to the attorneys at my firm.”

Show Me the Money

According to the research firm CB Insights, some 280 legal technology startups have raised more than $750 million since 2012. Although legal-tech funding fell 74 percent in the first half of 2016, compared to the same period in 2015, the field’s growth still has been astronomical since the Great Recession.

Linna, the Michigan Law adjunct professor, says that these startups and alternative legal service providers are impacting the marketplace for legal services, and that the impact will continue to grow rapidly. But he cautions that technology is not a silver bullet. “Some lawyers tell me that they’re just waiting to see which software and artificial intelligence solutions rise to the top and then they’ll implement them. This completely misses what’s happening. Forward-thinking law firms and corporate legal departments are disaggregating legal matters, breaking them into their component parts, and determining how to best accomplish the component tasks with people, process, data, and technology. These organizations are empowering everyone, not only the lawyers, to innovate, continuously improve, and deliver greater value for clients. They’re on the path to building learning organizations. You cannot buy that off a shelf.

“Second, some people in the legal-tech space are pushing things that aren’t real, things they can’t deliver on,” says Linna. “Unfortunately, this gives naysayers the opportunity to say that the buzz around legal technology is a bunch of BS. There’s no need to oversell these solutions. We can do some amazing things with people, process, data, and the technology available today. Lawyers need to be implementing solutions today so that they’re prepared for future advances. Some startups will deliver. Some will fail. That’s how it works in every vertical. Lawyers can’t bet the practice on startups. At the same time, lawyers must do a lot of hard work before they’ll be ready to harness the breakthroughs that startups deliver.”

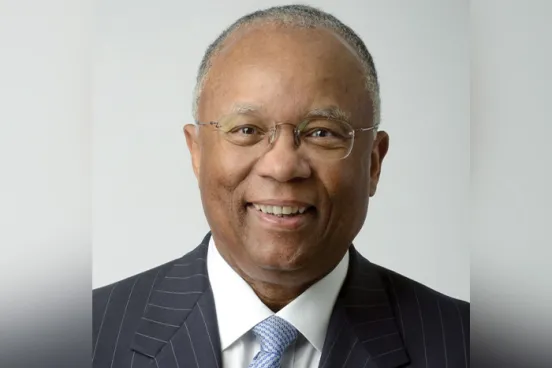

Plenty of startups are trying to deliver these breakthroughs. As an angel and seed investor with an interest in legal technology, Peter Krupp, ’86, seeks to separate the technological wheat from the chaff. He is a retired partner at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP. “I always thought that law firms could be utilizing technology more efficiently. So about 10 years ago I started talking to people who were involved with legal innovation,” says Krupp. These days, he reviews several legal-related investment pitches each month.

Krupp met Katz, the Chicago–Kent professor and LexPredict co-founder, about a decade ago. Krupp is not an investor in LexPredict, but he is an adviser to the company. “Beyond predicting outcomes, I liked that LexPredict had a broader application in terms of helping people get access to data. It gets to the larger, healthy debate going on right now about who owns the law,” says Krupp. “LexPredict is built on the benefits of predictive analytis, and I believe that the use of predictive analytics and AI will fundamentally change the way we practice law.”

Krupp’s current investment portfolio includes multiple legal-tech companies, including ones that use AI technology and other data science to review documents and solve issues, and another that uses statistics and data analytics to help predict which lawyers to hire. “I sift through and look at the addressable market, the size of the problem they’re trying to solve, and the amount of capital it will take to get to scale,” says Krupp of his decision-making process. “And then I check my gut feeling about the team.”

In Silicon Valley, where self-proclaimed next big things happen almost daily, Duncan Davidson, ’78, has shifted his career from the law of technology to funding the evolution of technology in the law and beyond. Davidson, who has an undergraduate degree in physics and math, came to law school knowing he wanted to practice computer law, an emerging field in the mid-1970s. He began his career at Cleary Gottlieb, where Bill Fenwick started a computer law practice before he left for Silicon Valley. Davidson then moved to the Left Coast to work at Irell & Manella, where he worked with another pioneer of the field whose “incredibly advanced” philosophy about computer contracts inspired Davidson’s approach. “He viewed contracts like construction projects. Instead of writing in clauses you can sue over later, build the software in a way that will work.” After a brief stint in venture capital, Davidson became a consultant and helped a floundering Apple Inc. avoid bankruptcy in the early 1990s. Others in his portfolio included AT&T, Hughes (which launched DirecTV), Intel, and Disney. “I told Disney that the new ‘information superhighway,’ the Internet, was the wave of the future, not cable,” Davidson says. “Years later, they conceded I was right.” Davidson went on to have two successful IPOs before moving back into the world of venture capital. Since 2010, he has been a general partner at Bullpen Capital.

The work suits Davidson, who swam against the current from his earliest days at Gottlieb. “Being an innovator is difficult because you know this stuff works, but you put it out there and others reject it because it doesn’t fit what they were taught,” he says. “Lawyers are more likely to look backward, while businesspeople look forward and embrace risk. I was increasingly drawn to the risky side of business.” The legal profession’s risk aversion makes investing in legal-tech especially challenging, Davidson notes. “Innovation is not occurring in law firms or legal departments. It’s occurring among the businesspeople who want to get around the legal department, and then it’s adopted by younger lawyers who recognize that it will make their lives easier. It’s almost got to overwhelm the powers-that-be before they officially endorse it.”

The team at Bullpen mostly looks at companies that sell to clients rather than to law firms, says Davidson. One company he has been exploring uses artificial intelligence to analyze patterns in patents, with potential markets in both the United States and China. Another, in which Bullpen has invested, does smart contracts (i.e., contracts written in code with self-executing provisions based on conditional logic) on the blockchain—a secure, unalterable, distributed record of transactions. “I think that the future we envision, with smart cities and self-driving cars, will not scale until we have really cheap smart contracts happening in the background,” says Davidson, who notes that the unpredictability of the future makes venture capital such a rush. “I get to look forward and make investment bets on what this vision might look like. I’m not sitting here worried about what might happen. I’m trying to help shape it.”

Amid the buzz over the burgeoning legal-tech industry, Ziegler says lawyers must stand their ground. “I get disappointed when I see a bury-our-head-in-the-sand approach. I’m equally disappointed when everything about technology is portrayed as magical. I’m an advocate for lawyers being enthusiastic and critical participants in what’s happening. I want lawyers to look for ways to put their stamp on new technology.

“Lawyers shouldn’t cede that ground to vendors, computer scientists, or venture capitalists. They should embrace, own, create, and contribute to the development of tools that can make them better able to serve in whatever capacity they act as lawyers,” Ziegler continues.

The rise of legal-technology companies raises questions for practicing lawyers beyond, Will this cost me my job, says Reardon, at the Illinois Supreme Court Commission on Professionalism. “How do we continue to regulate when there are new players who don’t have to abide by lawyers’ rules of ethical conduct because they aren’t lawyers? As we promote professionalism, we have to know what it means to be a profession.”

Democratizing the Law

Beyond innovations that make the existing legal system operate better, there are the wannabe clients who historically have been left behind by a system they can’t afford and/or don’t know how to navigate. Says Reardon, “If you look at access-to-justice reports and various studies about how 80 percent of the civil legal needs of average Americans go unmet, the question we have to ask as a profession is, ‘If we’re not providing legal services to the vast majority of citizens, what are we doing and where are they going?’”

Many are going to one of the most high-profile legal startup success stories, LegalZoom, or similar companies. Mentioning LegalZoom might cause neck hairs to rise or eyes to roll on the part of the legal establishment, but James Peters, ’03, says the company plays an important role in today’s legal landscape. He has been with LegalZoom since graduating from Michigan Law and currently is its vice president of new market initiatives. Peters originally wanted to pursue a public interest career, but “I thought it was interesting that there was this company that wanted to help ordinary people access legal services. I work for a for-profit company with a public-oriented purpose.”

Peters joined LegalZoom when it was just two years old. Today, it employs around 1,000 people and has helped nearly four million customers. While many traditional law practices struggled in the wake of the Great Recession, LegalZoom thrived. For one thing, layoffs and a lack of hiring across many sectors caused aspiring entrepreneurs to take the leap and start their own businesses. Also, uncertain economic times meant people wanted to reduce what they saw as unnecessary expenses, such as hiring a laywer. “We cater to both of those groups,” Peters says.

All of LegalZoom’s offerings were developed by lawyers, and for an additional fee, one of LegalZoom’s affiliated lawyers will review what the customer creates. That ability for interface with a practicing attorney—albeit through a computer—sets LegalZoom apart from its competitors, notes Peters. “We put a lot of people behind our operations, so customer satisfaction is a huge deal. We don’t just send people off to navigate technology; we back them up with access to a dedicated network of attorneys in every state.” In addition, Peters says that LegalZoom’s systemization of basic legal services, like incorporating a small business or creating a power of attorney, is advantageous to customers beyond saving them money. “The more you systematize, the less chance of human error. That’s why surgeons and pilots follow procedure checklists. Companies like LegalZoom that are using a technology-plus-people platform build those checks into the system to a far greater extent than private practitioners.”

He understands why the legal establishment is wary but argues that the company is building awareness of the value that lawyers, as a whole, provide. Through the company’s extensive advertising, “we are planting the seed that if you’re starting a company, you have a legal need. If you are starting a family, you have a legal need, whether you end up using LegalZoom or not. The more we educate the general population about their legal needs, the better.”

He also insists that LegalZoom is not in direct competition with traditional practitioners. “There aren’t a ton of people who are saying, ‘I was about to go to a typical lawyer, but I’m going to LegalZoom instead.’ Our customers are the people who either wouldn’t be likely to use a lawyer or who are looking for a type of service that falls outside of what most law firms provide. We live in a country where 80 percent of legal needs are unserviced. The biggest issue for anyone providing legal services in the U.S. is under-consumption from the public, not any particular competition.”

While LegalZoom’s business model merged legal access and technology from the get-go, Microsoft Corp. built its global empire in the technology sector and now is using its influence and expertise to increase access to justice. David Heiner, ’85, Microsoft’s strategic policy adviser, is helping to lead the charge. In 2016, Microsoft announced a partnership with Legal Services Corporation (LSC) and Pro Bono Net (PBN) to build a portal that will enable people to navigate the court system and legal aid resources, learn about their rights, and prepare and file basic documents. They will pilot the project in Alaska and Hawaii in 2018, with eventual sights on all 50 states. Microsoft is providing at least $1 million and project management expertise to build the prototype.

Heiner chairs the board of directors at PBN, a national nonprofit that leverages the power of technology and collaboration to help close the access-to-justice gap. PBN offers multiple technology solutions, including CitizenshipWorks and Immi, which are self-help websites that enable people to see if they qualify for citizenship and then apply, or see if they qualify for any basis to stay in the United States. PBN’s partnership with LSC and Microsoft merges personal and professional interests for Heiner, who has a bachelor’s degree in physics and has long been interested in technology, but also was attracted to the law in order to help promote access to justice. He served for many years as a vice president and deputy general counsel in Microsoft’s law department, where, in addition to overseeing the company’s antitrust work, in later years he was responsible for privacy, telecommunications, accessibility, human rights, and online safety. He now focuses on technology policy relating to artificial intelligence. “Microsoft’s mission is to develop technology and get it out to people in a broad, inexpensive way, to enable people to achieve more with their lives. A big part of that is sales, but we’re also looking for ways to showcase how technology can benefit society,” he says. For Heiner, who spent nearly two decades as Microsoft’s lead internal antitrust counsel, the project reconnects him with his longstanding interest. “Part of the appeal of going to law school was to help people who couldn’t afford a lawyer. I’ve always been intrigued by ways to combine legal skills with the technology angle to do that.”

The portal grew from a discussion group of state court professionals, legal aid professionals, and tech industry representatives that LSC convened. The group discussed how great it would be to have a comprehensive online resource for people with economic or logistical barriers to hiring a traditional lawyer, but shelved the idea for lack of funding. A subsequent meeting between LSC President James Sandman and Brad Smith, president and chief legal officer at Microsoft, reignited the project—and Heiner’s involvement. “When Brad asked me to lead the project, my first step was to bring on Pro Bono Net to leverage its experience in developing legal aid technology,” Heiner says. “My second step was to connect with our artificial intelligence researchers, who are doing state-of-the-art work in computational reasoning and understanding.”

The prototype will utilize Microsoft’s newest AI technologies, including ones that aren’t yet available in products—from inferring meaning from users’ searches (instead of merely homing in on key words) to directing users to appropriate resources, and even to providing predictions on likely outcomes, all with a conversational interface. “The goal is to help make sense for users of what can be a very confusing legal system.

“It’s hard for people to know if they have a legal problem and if there’s a legal solution, and then where and how to get started. AI can help,” says Heiner.

Lawyer 2.0

So how do lawyers and future lawyers add value in a profession where the value proposition is shifting?

“First-year associates need to show they have a value proposition, and a technical skillset is a great way to do so,” says Katz, the Chicago–Kent professor. “There are more opportunities now for them to make an immediate difference, instead of sharpening pencils for years before they’re drawn into meaningful work.” The tech mindset can be different for a profession traditionally grounded in the liberal arts—“I hear people say, ‘I didn’t come to law school to do math’ all the time,” says Katz—but it is changing. In Michigan Law’s fall 2017 entering class, for example, STEM majors accounted for 18 percent of the class (up from 11.5 percent in 2016) and included 11 math majors, the highest ever.

Also, new lawyers must prepare to adapt to a shifting landscape throughout their careers, says Ziegler, who teaches at Suffolk University Law School in addition to leading Harvard Law Library’s Innovation Lab. “We must teach students to be active participants and open-minded skeptics contributing to the design of technology; to distinguish marketing puffery from real value propositions; and to reconcile legal professionalism and legal ethics with all that technology makes possible.”

As Reardon has noted by the increased attendance at the Illinois Supreme Court Commission on Professionalism’s annual futurelaw conference, lawyers increasingly are embracing opportunities to talk about these topics. In 2014, Linna and Katz founded the Chicago Legal Innovation & Technology Meetup to accelerate the adoption of legal innovation and technology. “We are building a community of people who want to improve legal services for everyone,” Linna says. The meetups bring together practitioners, technologists, lean thinkers, project managers, academics, law students, and others interested in delivery of legal services, law and technology, and the importance of legal systems. “When we first started, it was mostly innovators and early adopters—people who were ahead of the curve. Now, we have many more traditional lawyers from legal departments, law firms, and legal aid organizations. We are seeing the marketplace continue to evolve,” says Linna.

Beyond technical competency and a willingness to learn, lawyers also must demonstrate their ability to work in cross-functional teams to solve problems. “My message in class is that law is a profession but also a business, so you’ve got to be able to collaborate across your business to understand the business impact of your legal decisions,” says Peters, the LegalZoom VP who also has taught at the University of Miami and Michigan State law schools. “Lawyers have to give solutions, not just spot issues.”

That paradigm shift toward problem solver opens up limitless possibilities, Reardon says. “We need to change the mentality of waiting until client matters get so bad that we’re heading to court. Technology can help us be more proactive. If we start thinking of our profession as more than just being hired guns, there’s a lot of promise.”

It’s a promise born from complex problems that will require equally complex systems—technological and otherwise—to solve. “While some fear that improved processes and technology will lead to fewer lawyers, the failure of lawyers to improve their services and provide value to clients is the greater existential threat,” says Linna. “By embracing these disciplines, lawyers can create the capacity to focus on solving ‘wicked’ problems, which continue to grow in number and complexity in our increasingly connected, interdependent world.

“It’s an exciting time. So much is happening in the world, and who better to lead the change than lawyers?”

Dan Linna, ’04It’s an exciting time. So much is happening in the world, and who better to lead the change than lawyers?

Problem Solving Initiative Trains Future-thinking Lawyers

“Law school can get very in the weeds,” says Katie Hart, a 3L. “All your classmates are learning how to speak the same language. But to be an effective lawyer, you need to communicate with clients who won’t be fluent in legalese.”

Have Your Day in Court Without Being in Court

A day in court is never a day at the beach. But for those who have trouble juggling work and family responsibilities in order to appear in court, or lack a way even to get there, something as minor as a traffic ticket can become a seemingly ceaseless stressor.

A Praktio Education in Contracts

Michigan Law Professor Michael Bloom says that learning to work with contracts is like learning any language. “So if software can help you learn Spanish or Python, why can’t it help teach you to read and write contracts?”

![The Tech [R]evolution in Law The Tech [R]evolution in Law](/sites/default/files/styles/main_banner/public/2023-03/The-Tech-%5BR%5Devolution-in-Law.jpg.webp?itok=Lo4nK5HU)