When you arrived for a hearing at Michigan’s 36th district court before 2020, the most important question you might face was: where do you put your phone?

Located in Detroit, the 36th District Court is the state’s busiest—it’s also the one that serves the most self-represented litigants. The courthouse long barred cell phones yet provided no cell phone lockers. So if you arrived with your phone, you’d be forced to choose to miss your hearing—and perhaps have a warrant issued for your arrest—or stash your phone in the bushes until your hearing was over.

The practice was so well known that the bushes became a popular spot for cell phone thieves. If you were disabled and depended on a taxi or ride-hailing app like Uber to get to court, or you were a single parent forced to leave kids at home and out of reach, this rule alone could make it impossible for you to access justice.

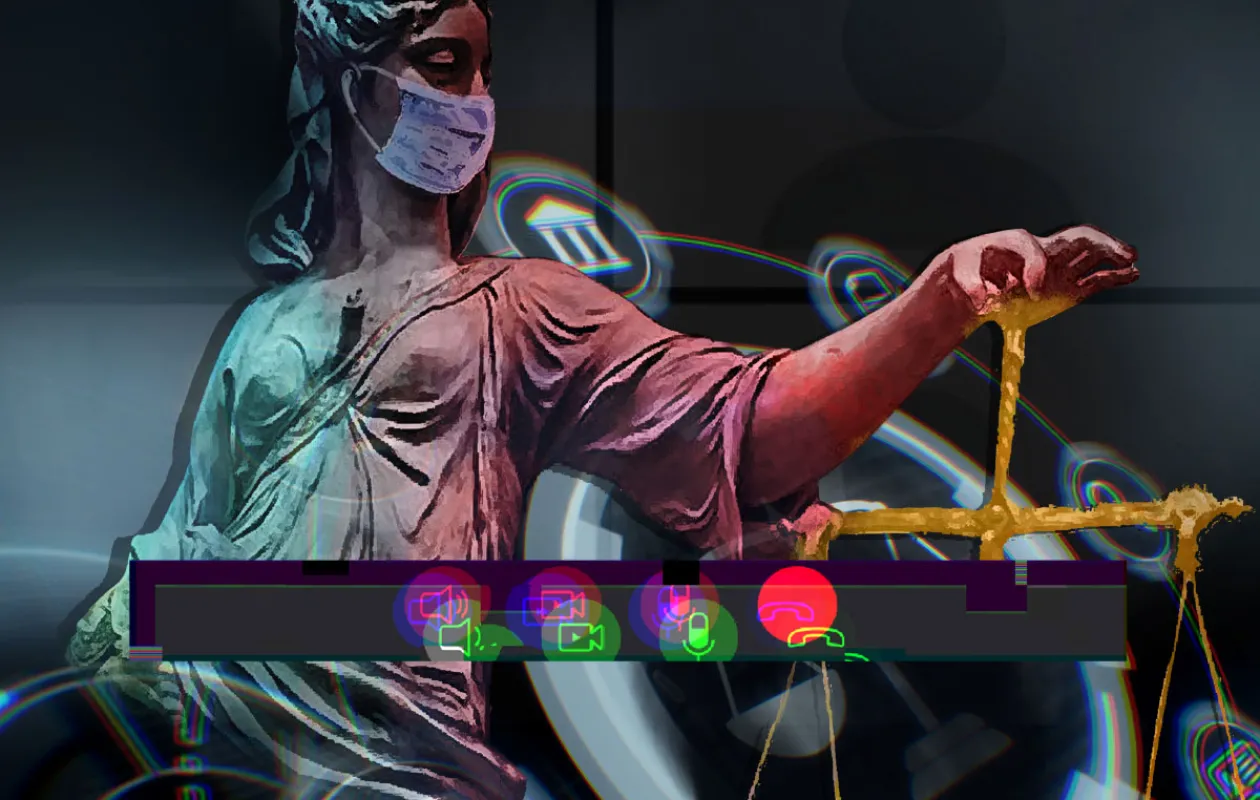

Michigan’s courts, like many across the country, confronted a phobia of even the most basic technology when COVID-19 hit, replacing it with a rush to take the antiquated judicial system online.

Chief Justice Bridget Mary McCormack of the Michigan Supreme Court, who is also on the Michigan Law faculty, wrote in an op-ed that the pandemic has forced jurists to ask, “Why is our system of justice held together with the threads of 20th-century technology and 19th-century processes?”

Michigan’s Supreme Court had been nudging lower courts to modernize before the pandemic hit, but it was slow going. The Supreme Court barred courts from banning cell phones shortly before lockdown began and had provided judges Zoom licenses for years. But hardly any judges used the technology.

When COVID-19 turned the world upside down, McCormack, who serves as co-chair of the Post-Pandemic Planning Technology Workgroup of the Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrators, saw an opportunity.

“Sometimes it’s only through disruption that you really can make the kind of change that is more fundamental,” says McCormack.

Between March and August of 2020, Michigan judges conducted more than 1 million hours of hearings by Zoom, McCormack says. The state also expanded an online dispute resolution system that enables people to fight traffic tickets, evictions, and other matters through their computers or phones rather than appearing in court.

These steps not only make courts more efficient, they have the potential to make justice easier to access for millions of Americans who don’t have the time or know-how to navigate the courts on their own. Technology obviously doesn’t solve all problems—and unequal access to reliable internet creates problems of its own—but, McCormack says, it addresses many of the longstanding challenges that keep people from getting a fair hearing in the courts.

Concerns about access to technology “pale in comparison to the access to justice concerns that predated March 2020—like transportation, childcare, language barriers, all the ways in which people were just simply not showing up to court,” says McCormack.

The experience during the pandemic has already shown how technology can reduce barriers to justice. Now the fight is to keep the momentum for change growing nationwide.

“This is a moment where we have to be really thoughtful about what things make sense,” says McCormack. “I am worried that now that we have a vaccine, everybody will want to backslide to the way it used to be.

Michigan Supreme Court Chief Justice Bridget Mary McCormack“Why is our system of justice held together with the threads of 20th-century technology and 19th-century processes?”

The Race to Get Online

The speed with which some jurisdictions have moved to get online since COVID-19 hit is mind-boggling. In Texas, for instance, “we were basically at nothing on March the first [2020],” says David Slayton, administrative director for the Texas judicial branch. No online hearing had ever been conducted in the state, and the Texas courts did not have Zoom licenses. But the state courts were determined not to interrupt their services amid the pandemic.

“When the world around us is in chaos, the judiciary … needs to be consistent and available—that was our motto,” says Slayton.

Within four hours of the Texas governor declaring an emergency on Friday, March 13, 2020, the state Supreme Court issued orders allowing judges to hold remote hearings. The Office of Court Administration spent the weekend exploring teleconferencing platforms. By Monday, they’d recruited about 20 judges for a test run, and the judges gave Zoom the thumbs up. Even Slayton seemed surprised by the response.

“Within two days, [the judges] reported back, ‘Oh my gosh, we definitely can do that!’” says Slayton.

The state immediately bought Zoom licenses for its 3,000 judges. Since then, two-thirds of judges have become regular Zoom users, holding more than 800,000 hearings statewide. The state also started livestreaming court proceedings on a centralized website, streams.txcourts.gov, in order to ensure the public’s right to observe court proceedings.

Texas has even begun experimenting with remote jury trials for minor offenses, holding more than a dozen over Zoom. They started with low-stakes cases, such as traffic offenses.

“It was a huge success,” says Slayton. “We’re now doing a couple a week.”

Federal courts, too, switched to remote hearings and have been operating with great success, says Judge Roger Gregory, ’78, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

“We haven’t missed a beat,” he says. Gregory also sees potential for technology to diversify the pool of law clerks. He plans to do interviews for potential new clerks remotely going forward, opening those jobs to applicants who may not be able to fly in for an in-person interview.

“I think that opening up access to opportunities for people to clerk and broadening diversity in the judiciary are good things we should plan on continuing,” says Gregory.

But as far as oral arguments go, “we’ll go back in court as soon as it is responsibly safe to do so,” says Gregory. “I think the judges missed that.”

It doesn’t necessarily take rewiring court systems from top to bottom for technology to dramatically smooth the process of navigating the courts. One tool that’s helped hundreds of thousands in Michigan is a website called Michigan Legal Help, which provides advice and self-help tools for Michiganders handling their own legal issues without lawyers.

The initiative, funded in part by the Michigan Supreme Court and the Michigan State Bar Foundation, launched in 2012. But its use has exploded since COVID-19 hit, says Angela Tripp, Michigan Legal Help’s director. The site has been getting around 60,000 visits per week since March of last year, a 36 percent increase compared to the previous year. Every day, around 350 people use their online tools to generate the forms they need to do business in the courts—everything from the paperwork tenants needed to invoke the Center for Disease Control’s moratorium on evictions to the forms to file for divorce.

During the pandemic, Michigan Legal Help has worked with courts to take even more business online. In Detroit, for instance, the platform worked with the Third Judicial Circuit of Michigan to allow people to file for personal protective orders directly through an online portal.

One place online tools may have an important impact during the pandemic is with evictions. Most tenants facing eviction don’t have attorneys; many can’t even make it to their eviction hearings and just move out of their homes without putting up a fight. But Michigan Legal Help’s website has made filling out the paperwork to invoke the CDC’s eviction moratorium relatively easy—it’s been used by 200 to 300 people each week—and Zoom hearings have made it easier for tenants to show up to hearings on their cases.

“It has been pretty incredible the way technology has increased access to justice,” says Tripp. “One thing it has really done is gotten more people to engage in their court hearings.”

What is a Court, Anyway?

Bringing America’s courts into the 21st century requires more than simply integrating remote hearings and electronic filing systems. It requires fundamentally rethinking the role of courts and the services they provide, and then connecting them to users in ways that make sense in modern life.

That’s according to J.J. Prescott, Michigan Law’s Henry King Ransom Professor of Law and co-director of the Empirical Legal Studies Center. For too long, courts have been conceptualized as physical locations rather than a “nexus of services … a set of people or tools or processes that help to resolve disputes.”

In many cases, Prescott says, there’s no good reason the parties to a dispute need to meet face to face, or even engage on a matter at the exact same time. Traffic tickets, evictions, and other civil matters are far more easily resolved online, where parties can lay out their cases in writing. This doesn’t require anyone to take time off work, and it can even help remove bias from cases, since it’s possible for the dispute to be adjudicated without judges ever seeing what someone looks like.

This premise is at the heart of Matterhorn, an online dispute resolution system that emerged from Prescott’s U-M Online Court Project in 2014, which turned into a company with help from the University of Michigan’s Office of Technology Transfer. Last August, Prescott won U-M’s Distinguished University Innovator Award for this work.

Matterhorn is now running or about to start operating in 21 states, with more than 150,000 cases moving through its system. It’s used more extensively in Michigan than anywhere else, operating in dispute resolution systems in every one of Michigan’s 83 counties. That’s nearly five times the number of counties in which Matterhorn operated at the start of the pandemic. The system spread fast as the courts responded to COVID-19, and the company’s reach is now about three times what the company expected at this point, says M.J. Cartwright, Matterhorn’s CEO.

“We’re talking about a lot of people who we know we’re helping—especially during a pandemic. They don’t have to go to court to deal with their cases and can be much safer,” Cartwright says. “People are realizing they need to do this sooner rather than later.”

“I was gung-ho when they first approached me about it,” says Andrea Andrews Larkin, Chief Judge of 54B District Court in East Lansing, one of the first judges to put Matterhorn into practice.

The opportunity to take court business online seemed especially useful in her area near Michigan State University—students were far more comfortable conducting business online.

Her comfort with technology made her one of the most innovative judges in responding to the pandemic. She was especially concerned about her treatment courts for people dealing with addiction, who were used to seeing a judge every two weeks to stay on track.

“We have a system now that I think is as good as any in the state to keep true to the program and what’s supposed to be the close, frequent monitoring,” says Larkin. “And it’s working.”

Kim Thomas, Co-director of Michigan Law’s Civil-Criminal Litigation Clinic“I think on the criminal side, things have been more of a mixed bag than they have been on the civil side.”

Criminal Matters Remain a Challenge

Technology has not solved all the challenges for courts operating during the pandemic, of course. While online tools have kept many civil matters—and some minor criminal ones—running, it’s been far more difficult to handle serious criminal cases without being able to give defendants their day in a physical court.

“I think on the criminal side, things have been more of a mixed bag than they have been on the civil side,” says Kim Thomas, who co-directs Michigan Law’s Civil-Criminal Litigation Clinic.

There have certainly been advantages to shifting online. By far the biggest, Thomas says, is that the pandemic has forced policymakers to take a hard look at whom they put in jail and why. Detention is being used far more carefully in order to slow the spread of COVID-19 in jails.

“There’s been a recognition of how unsafe it is to be in jails and prisons right now, given the inability to socially distance,” says Thomas. “It’s caused us to think about questions that we should have been thinking about already, as to whether or not someone needed to be held pre-trial or on a minor case, or whether [someone convicted needs an] incarceration sentence or a community sentence.”

Online hearings can be useful for some matters involving defendants who are not in custody. But it may never be possible to have jury trials in serious criminal cases outside a courtroom, Thomas says, and the Constitution is one big hurdle to taking criminal proceedings online. The Sixth Amendment, which guarantees defendants the right to confront witnesses, may not be satisfied unless a defendant can come face to face with them in a courtroom. It may also be essential to have face-to-face trials in cases where jurors need the opportunity to assess the credibility of people involved in the case.

“I do think that the ability to have fair hearings—and especially the ability to have jury trials on the criminal side—is much more challenging,” says Thomas. “People who have committed incredibly serious crimes are in custody, and they’re awaiting trial with no end in sight.”

This has created a Catch-22 for those facing serious charges, Thomas says. “Do you insist on your constitutional right to a jury trial? Or do you plead?” Thomas says, and notes that more research is also needed on how video conferencing affects judges’ and jurors’ responses to defendants and witnesses.

There’s reason to worry that video hearings blunt judges’ empathy for criminal defendants, for instance. A 2010 study found that bail amounts jumped 51 percent—$21,000—when the Cook County, Illinois, jail began using video for initial bail hearings. And a recent report from the Center for Court Innovations and the National Legal Aid and Defender Association highlighted the ways videoconferencing affects the nonverbal cues people rely on to assess credibility.

Take, for instance, eye contact, which we treat as an important signal of sincerity and attentiveness. Video conferencing systems make eye contact impossible—often a user has no idea of the right camera angle to simulate eye contact. If a defendant or a witness appears to be looking down or away from the camera, will judges or jurors discount their credibility?

One study, which examined how credible child witnesses were perceived to be when testifying by video, found children were perceived as “significantly less accurate, believable, consistent, confident, able to testify based on fact not fantasy, attractive, and intelligent.”

This experiment was conducted in 2001 using closed circuit television, so it’s possible viewers would react differently today now that screens have become ubiquitous. Some judges have reported they believe they get more candid answers from child witnesses over Zoom, since the kids don’t have to testify in the intimidating setting of a courtroom. But until this is systematically tested today, there’s reason to worry Zoom hearings may skew outcomes.

“We just don’t know that much about how making decisions over Zoom impacts people’s perceptions and impacts their decision making,” says Thomas.

But Zoom hearings may also help humanize the people involved, says Judge Larkin of Michigan’s 54B District Court. The chance to see litigants in their homes “gives me a window into their lives that’s deeper than what I can get in a courtroom”—people Zoom in with babies on their laps, for example.

Sometimes that window can open a little too wide. She once began a hearing to discover a litigant Zooming in from bed, wearing lingerie with her shirtless partner beside her.

As valuable as technology is, Larkin says, incidents like this are a reminder that there is still a value to appearing in a physical courtroom.

“The courtroom experience lends the amount of gravitas that I think these hearings deserve or need,” says Larkin. “There’s something about actually being in the courtroom that impresses upon you the nature of our constitutional system of justice, and I think a lot of that is lost on a Zoom call.”

But, she said, it was a net win. “There are definitely advantages for litigants and parties in the system,” she says. “For that reason I don’t think we’re ever going to go back to where we were before this started.”