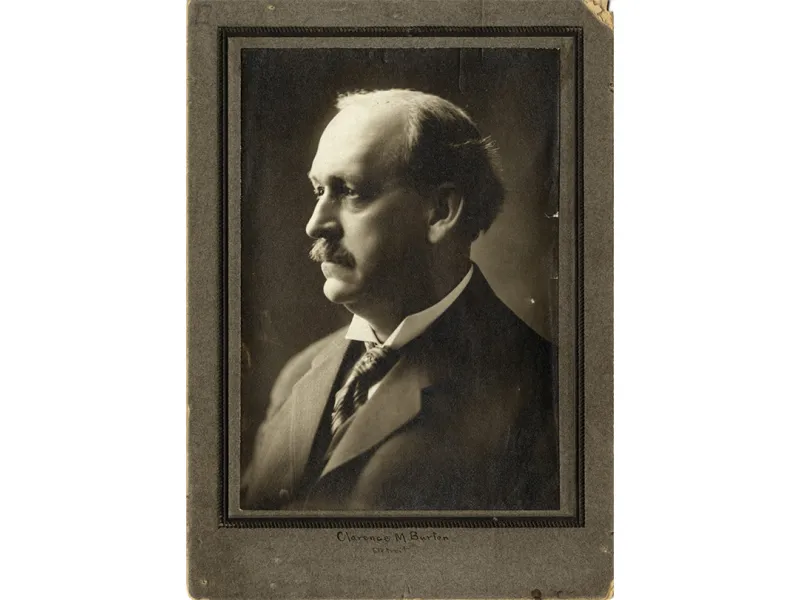

Alumnus Clarence M. Burton traveled the globe to acquire historical documents. His collection—including some 500,000 books and 250,000 images—spans 400 years of North American history and is regarded as one of the best in the nation. On May 21, the Detroit Public Library will commemorate its 150th anniversary and the 100th anniversary of the Burton Historical Collection.

One day in 1929, in Detroit, Clarence M. Burton wrote a short—well, let’s call it terse—letter to a gentleman in Cleveland. He was requesting information about the University of Michigan Class of 1873. The class was to have a reunion, and University officials had asked Burton, an 1874 graduate of U-M’s Law Department, as it was then known, to help track down class records. Burton had learned that the man who had been secretary of the 1873 class, and thus responsible for keeping track of its members, had died, and that somehow, all of these long-maintained records had vanished.

Burton was better than anyone at discovering what could be found or determining, if said materials could not be located, why not. He also was tenacious at replacing them via other records, interviews, or similar methods—including blunt questions when warranted. Which brings up the 1929 letter.

It went to a Mr. H.M. Farnsworth, an attorney in Cleveland, where the deceased secretary had lived.

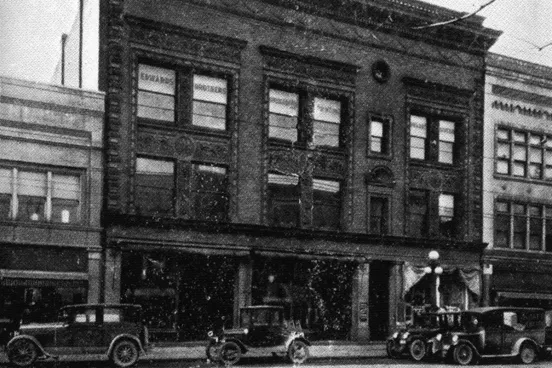

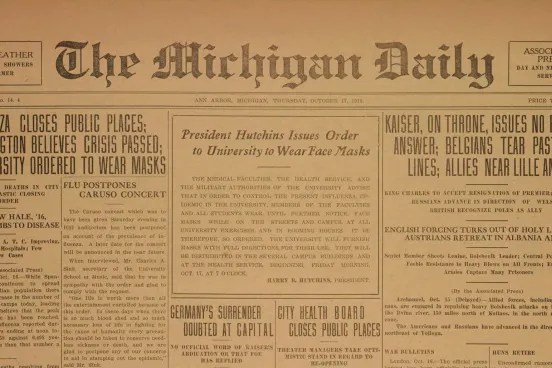

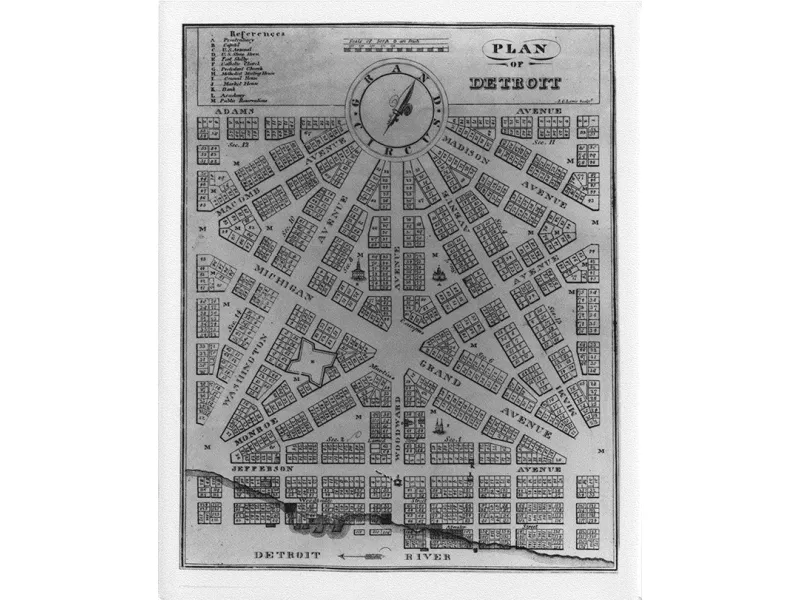

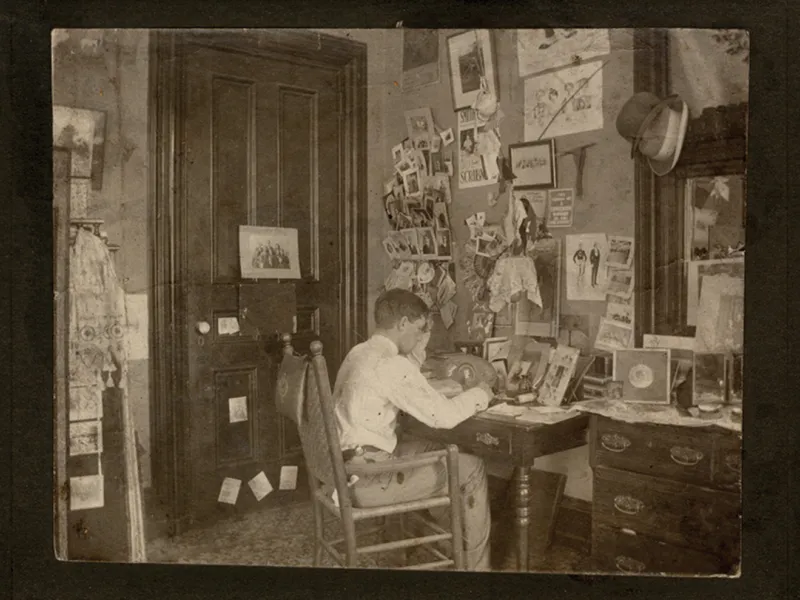

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Images for the burton story

Dear Sir,

At the risk of annoying you, I again write for information regarding the papers of the University Class of 1873, that were in the possession of Mr. Frank E. Bliss at the time of his death. Were these papers actually destroyed, or were they sold to some junk dealer? If they were sold to some dealer, they will be transmitted to some paper mill. This collection of papers is confined to a few dealers. I have heretofore been able to trace papers to the mills, and recover them, and might possibly in this case, if I could get a start.

Before applying to the paper mills, will you answer my question as to the actual destruction of the papers?

Mr. Farnsworth duly responded three days later, writing:

I regret to advise you that after conference with Mr. Bliss’ children who are reachable here, it is said that the U. of M. papers were all placed in the china cabinet. This china cabinet was sent to the home of one of the children here who reports that there were no papers in the cabinet when it reached his house so that I fear that any search for them will prove futile.

Clearly, Mr. Farnsworth knew little of the tenacity of Burton—who had had personal encounters with chicken coops and outhouses in his lifelong searches for forgotten or assumed-missing historical records, books, and papers dating back to the time of Cadillac and Napoleon. Still, this case was hopeless, so soon after receiving Farnsworth’s letter, Burton wrote to one U-M alumnus that “in order to make up a record of the Class of ’73, we have practically got to start at the very beginning.” He then composed an information survey that he sent to every living member of that class. He succeeded fairly well in his goal, and received grateful acknowledgement from University leaders.

Burton was 76 years old and essentially famous when he worked on this project. He owned one of the nation’s leading title and abstract firms, and was a renowned historian. That he still was willing to traipse through paper mills in this search would have surprised no one who knew him.

Burton had been collecting everything imaginable related to historical documents for nearly 60 years. Twenty years before he wrote Farnsworth, his expertise and his collection, which he kept at his ever-expanding Detroit home, were already well known.

“No resident of the state has a wider and more intimate knowledge of its history, even to the most obscure details than has he…,” stated a short biography of Burton in the 1909 volume, Compendium of History and Biography of The City of Detroit and Wayne County, Michigan, by Henry Taylor & Co.

“Mr. Burton’s pride in his private library, one of the best of its kind in the middle west, if not the entire Union, is well justified, and no man in the state is more intimately informed upon its history.”

Just a few years after this book was published in 1914, Burton decided to donate his vast private collection to the Detroit Public Library. One year later—100 years ago—the library formally debuted its Burton Historical Collection (BHC). It consisted of 30,000 volumes, 40,000 pamphlets, and 500,000 unpublished papers.

These papers constituted, as one writer put it at the time, “the memory of Detroit.” It also was the memory of much of the state of Michigan and the Old Northwest. So it was no wonder U-M officials called Burton, renowned historian and faithful alumnus—as well as a well-known real estate attorney in Detroit and the city’s long-serving “historiographer”—for help tracking down the Class of ’73.

Uniquely Significant

Burton first got the idea to start what would become a lifelong obsession in 1874, as a 20-year-old U-M student. Burton showed up to hear an evening lecture on campus. The speaker’s subject was “The Northwest in the Revolution,” and he exhibited a 1780 account book. He recommended that all men adopt a hobby outside of their profession. As Burton often related in his later years, this speaker shared that his own hobby was local history. That very day, Burton resolved to collect one book or item of history each day going forward.

And, to use a threadbare but accurate cliché, the rest is history.

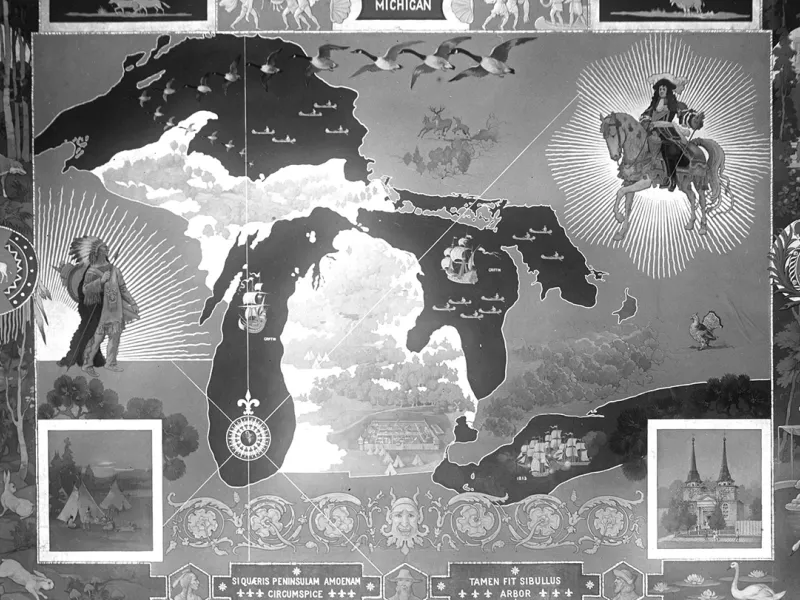

Today, the BHC offers to the public more than 500,000 books, 250,000 images, 4,000 manuscript collections, and about 1,000 newspaper titles—some 400 years of North American history. It is regarded as one of the best such collections in the nation. While originally centered largely on the history of Detroit, of Michigan, and of the Northwest Territory, “there are materials on virtually every aspect of early American history, such as the Salem witch trials, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the California Gold Rush, slavery, and the Civil War, in the Burton Collection,” says Mark Bowden, BHC coordinator for special collections.

Over the years, the collection expanded as Burton and others added to it, Bowden says. “During his lifetime, people would often contact him when they found something they thought might interest him. He even visited European archives mining for documents related to Detroit and bringing back copies and transcriptions.” Bowden says that BHC also offers “one of the largest genealogical collections—worldwide in scope—in the country.”

Margaret A. Leary, librarian emerita of Michigan Law, describes Burton as a “uniquely significant University of Michigan law graduate who contributed to the University, the city of Detroit, and the state of Michigan during his life.” Through the Burton Historical Collection, he left a lasting legacy, she says. “He was also a generous donor to the University, giving many invaluable books to the University Library, and was instrumental in raising money for Alumni Memorial Hall. Although Burton died 83 years ago, the buildings, institutions, and historical collections he created have benefited thousands of people.”

Cellars, Attics, and Chicken Coops

Burton first studied science at U-M, then switched to liberal arts, then earned his degree from the Law Department. According to a 1953 biography written by Patricia Owens Burton, Burton’s grandson’s wife, he did not actually receive his liberal arts diploma because he refused to pay the fee the University charged for it. “Nevertheless,” Patricia Burton wrote, “years later (after the Burton name became famous) the University awarded him the diploma.”

After earning his law degree, Burton, not quite 21, headed straight for horse-drawn-streetcar-era Detroit, which then had about 80,000 citizens. He took a job with Ward and Palmer, real estate attorneys, for $100 a year, and “soon made himself indispensable,” according to the Cyclopedia of Michigan, published in 1900. His job included researching the history of land titles, which required him to look at all varieties of old records. This cemented his lifelong passion for collecting historical items. He thereafter spent more time on this avocation than his career.

But the latter was hardly an afterthought. John Ward, one of Burton’s bosses, started a title abstract firm with his nephew. Burton joined, prospered, and, by 1891, had organized the Burton Abstract Company, later to become the Burton Abstract and Title Company. It became one of the nation’s largest and most successful such firms.

As he grew in influence and wealth, Burton moved into a larger home, now demolished, on Brainard Street, between Cass and Second Avenue. It was this home that became the repository of his burgeoning collection. Burton soon added a third story, which afforded him a large study.

“My earliest recollections are of this large, airy, and brightly-lighted room all lined with books,” wrote his son, Frank, in the 1951 book When Detroit Was Young. Burton worked long days at the office, then enjoyed his family through dinnertime and his children’s bedtime. After that, he was in his study for hours working on his collection. By 1892, Burton added a fireproof wing at the back of his house, “guarded by double steel doors,” Frank wrote.

“…Day by day boxes of books and manuscripts arrived, some from local sources, others from the East or from London….” Catalogues poured in from London, Boston, and New York. Burton perused them, chose what he wanted, placed orders. Before long, another wing was added to the house.

Frank reported that his father was “constantly searching for elderly men and women who had lived in or near Detroit.” When he found them, he interviewed them, stenographer at the ready. “By constantly questioning the descendants of early Detroiters and also the tenants occupying the old homes of early settlers, he would frequently learn of old boxes or trunks full of letters, books, or other records. Often these were in cellars, attics, chicken coops, and other out-buildings,” and people gave the papers to Burton, or agreed to take small payment for them.

Just a few examples of the treasure that became the BHC:

- The papers of Antoine Cadillac, founder of Detroit, about whom Burton became a foremost expert.

- The original Pontiac Journal, about the Ottawa chief who led a siege against Detroit in 1763. The Journal had last been seen in the 1840s. Burton found it after wielding a pitchfork to scoop up papers littered all over the floor of a home.

- The Potier Account Book, 1733-1751, a handwritten record kept by Father Pierre Potier at the Mission for the Huron Indians near Sandwich (Ontario).

- Early 1600s-era Catholic Jesuit missionary reports.

- Letters by Father Gabriel Richard, a Detroit priest and early supporter of U-M.

- Records of military men who served at the early French forts: Pontchartrain, Detroit, Lernoult, and Shelby.

- Original records from 1760 to 1820 of John Askin, a Detroit merchant, fur dealer, and commissary of the British Army in Detroit. These—Burton’s chicken-coop find—helped resolve disputed points about the War of 1812.

As rare books and items became scarce, Burton devoted his time to writing books about history, which remain invaluable sources. He also worked with a long list of organizations. It was when Burton built a new home in Detroit’s Boston Edison neighborhood in 1915 that he decided to donate his Brainard Street home and his collection to the Detroit Public Library.

Generosity to U-M

Throughout his adult life, Burton was heavily involved and invested in his alma mater, although most of his attention was directed toward the general University rather than the Law Department.

The Clarence M. Burton Papers, the personal 115-box archive at BHC, house dozens of letters from U-M officials dating back to the 1800s. Several letters document Burton’s central role and generosity of donating rare, virtually priceless books to U-M. One sheet from the librarian thanks Burton for finding Edward Gibbon’s multi-volume The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, among other books.

The 1900-published Cyclopedia notes in a small biographical sketch of Burton that his “generosity and public spirit are evidenced by his gifts to the University of Michigan of a great collection of works on the French Revolution and, later, of the first installment of that costly and monumental publication, Stevens’ Facsimiles of European Archives Relating to American Affairs at the Era of the Revolution.”

U-M awarded Burton with a third degree, an honorary master of arts, in 1905. Nearly a century later, in 2002, the Burton family donated a small cadre of papers to U-M’s William L. Clements Library.

One especially intriguing U-M-related item in Burton’s files is a letter he sent in 1875 to a publisher of a monthly magazine asking if it would be interested in publishing his history of the University of Michigan. The tissue-thin paper bears his heavy brown pen-and-ink handwriting. With the letter are 28 legal-sized pages, handwritten, tied together with a bit of yarn. They detail U-M’s history through the eyes of a then very young Burton.

He describes early Northwest Territory days, the first graduating class in 1845 of 11 young men, and in 1859 the opening of the Law Department with its first graduating class of 16 students a year later. He notes “one very important change in University affairs, which took place in 1870, was the admission of women….”

His affection for U-M is obvious. Of the Civil War era, he writes, “The war came with its call for soldiers and Michigan may well be proud of her University if for no other reason than for the number of young men who went forth from its halls to preserve the honor of the nation. When the end came…many of them came back to finish a course of study so abruptly broken off.”

But it is his final paragraph that captures the U-M heart:

“Michigan has erected, primarily to her own sons and daughters—secondarily to the whole world, a University which deserves the name: its rapid growth, its popularity, its faculties and the number of its students, each and all bear witness of the good it has done and is doing and predicts the good it will do for all who wish to obtain an education and are willing to work for it.”

On May 21, the Detroit Public Library will commemorate its 150th anniversary and the 100th anniversary of the Burton Historical Collection. www.detroitpubliclibrary.org