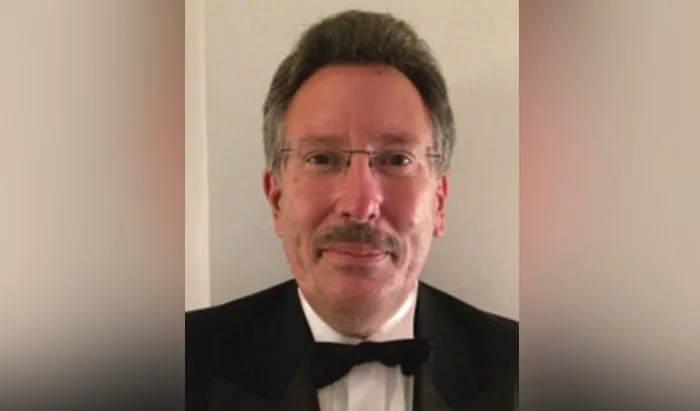

It started with a phone call from a West Coast lawyer seeking some basic legal advice about the auto industry. Then a few more calls, primarily from California and Europe. Before long, Richard Walawender, ’86, and other members of the automotive group at Miller Canfield PLC realized they needed to start a new team that would focus specifically on autonomous vehicles.

“Many of these companies are getting involved with the automotive industry for the first time. They are software providers and other companies that had no exposure to the way the automotive industry does certain things,” says Walawender, principal at Miller Canfield in Detroit and New York, co-leader of the firm’s corporate group, and director of the international and automotive practices.

“We realized we needed to institutionalize our focus on autonomous vehicles within our automotive group and bring together a team with transactional, IP, regulatory, and product-safety experience,” he says.

In doing so, Miller Canfield became what it believes to be the first major law firm to establish a full-service autonomous vehicles team to provide legal consultation, documentation, and practical insight to clients in all aspects of autonomous vehicle and automotive industries.

Other law firms also are taking on clients that manufacture driverless cars or supply software or parts to them. Additionally, automotive companies and software companies are having in-house counsel handle many of the legal issues in this rapidly changing area of the law.

Attorneys are addressing safety and liability issues, financial transactions when companies such as automakers acquire or join forces with technology companies, regulatory concerns as governments begin to establish guidelines for autonomous vehicles, and more.

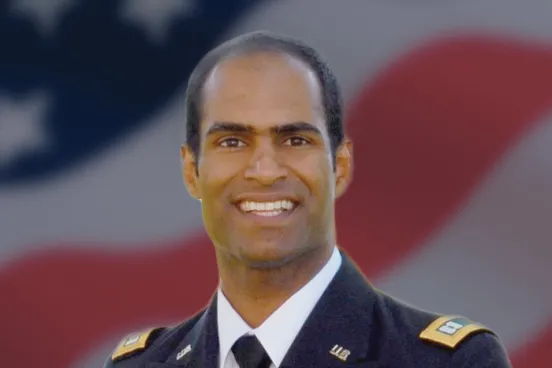

The scope of the legal issues that will be impacted as more autonomous vehicles hit the roadway is vast and will affect many areas of legal practice, says Donald Parshall Jr., ’79, senior counsel at Nissan North America. He says the legal issues surrounding automated and connected vehicles “fall into several buckets”: “In one bucket, you have the current product liability scheme, in which it is generally understood that the vehicle rarely causes the accident. With autonomous vehicles, if they bump into each other, it’s probably going to be alleged that the vehicle caused the collision.”

Much of the tort system in the United States is configured to deal with vehicle accidents and drivers suing one another, he points out. To the extent many of these accidents don’t happen, there will be a change. “The change will be gradual, but with this whole infrastructure being driven toward a tort system that is going to dramatically change, there’s a whole lot of lawyers who aren’t going to be able to [work on auto-accident cases] for a living.”

As for his work at Nissan, Parshall says that much of his focus is not on autonomous vehicles per se, but rather the emerging technologies that are becoming the basis for autonomous vehicles: emergency braking, intelligent cruise control, and other tools that supplement a driver’s reactions. “Ultimately, taken together with some additional technologies, these become the building blocks for autonomous vehicles,” he says.

Emily Frascaroli, counsel for Ford Motor Co. and a lecturer at Michigan Law who teaches a class about the legal issues involved with autonomous vehicles, focuses on safety and liability issues as they relate to autonomous vehicles.

She says that attorneys who focus on these issues often work at or with traditional automakers, but there also “are a lot of nontraditional players and new types of relationships in the space,” she says. She cites technology companies and others, many of which are accustomed to a faster pace of bringing products to market than automakers traditionally have been. Her primary goal, she says, is the assurance of safety before the cars reach the marketplace. The timeframe for such a level of assurance, she says, remains unclear. “Like any good legal issue, there are no magical answers.”

At Miller Canfield, Walawender’s team is working with three types of clients: traditional auto industry clients; new entrants into the market, such as software-sensor companies that have never worked with the auto industry; and municipalities and public-sector agencies.

Many of the new entrants into the auto industry are unaccustomed, for instance, to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) regulations. “We have a lot of experience working with NHTSA, so we advise clients on what they need to know to follow the regulations and what to anticipate in the future as NHTSA drafts regulations specifically for autonomous vehicles,” Walawender says.

His team also represents companies on joint development agreements, which are becoming more important in the autonomous-vehicle realm, as suppliers and their customers need to figure out how to make their new software and sensors work together with a car’s existing electronics. “You’re introducing a new set of software and technologies to existing electronic controls and systems, so a standard software license agreement ususally won’t be sufficient; the paradigm is shifting. It’s not like you’re just going to supply a software program and call it a day; they have to be integrated into software provided by a lot of other software developers,” he says. For attorneys, that means that “integration and joint development agreements are becoming more and more common.”

Data privacy is sure to become a bigger issue in the United States than it is now, he predicts. “I do a lot of work in the European Union; the United States doesn’t regulate data like they do in the EU, but I think that is coming,” he says. “The software that is being embedded in these vehicles is going to be able to serve as an event data recorder, like a black box on an airplane. Who owns that information, and who has access to it, is certainly going to be addressed legislatively.”

His firm also is working with public-sector clients, he says. “State- and county-level municipalities are very interested in this because they know they have an important role to play with connectivity of vehicles and who owns the infrastructure with which the automobiles connect. They’re starting to look at how they can finance this, and what’s their exposure and liability if a system goes awry.”

The United States is far from the only country interested in driverless technologies. The issue is of great interest in the European Union, and many Europe-based automakers are making significant advancements with autonomous technologies. In Asia, many recognize a critical need for such vehicles. Walawender moderated a panel at a conference last year about the autonomous vehicle sector where one of the co-sponsors was the China General Chamber of Commerce—U.S.A. “China is very interested in this. It’s a matter of not only safety but also of being able to accommodate the traffic patterns and preventing gridlock.

“This is definitely a global effort,” he adds.

Read more about the ways the private sector, government, and academia are preparing for a driverless future in our coverage of a Michigan Law conference at quadrangle.law.umich.edu.

![The Tech [R]evolution in Law The Tech [R]evolution in Law](/sites/default/files/styles/teaser/public/2023-03/The-Tech-%5BR%5Devolution-in-Law.jpg.webp?itok=Obrll94p)