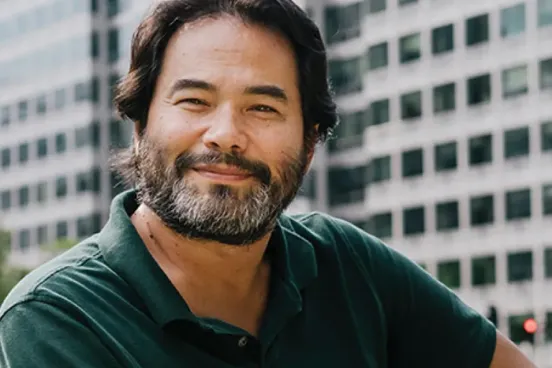

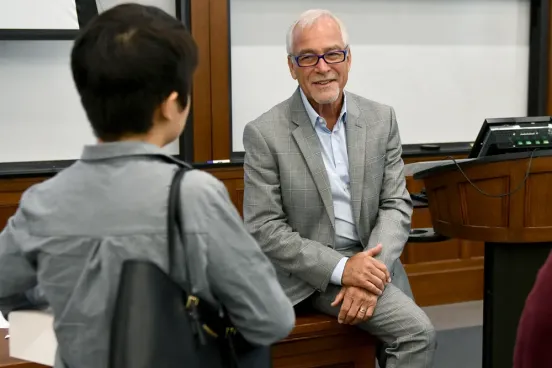

Nineteen years after wearing the winged helmet, Terrence Quinn’s college football coach, Lloyd Carr, praises his listening skills. “Terrence always paid attention, so I had confidence that he would remember what he was told and know what to do.”

At two critical junctures, however, Quinn, ’02, didn’t listen—first, when his high school coach said he never would play for Michigan. Quinn made the team as a walk-on and later earned a scholarship. He was a part of the 1997 national championship team, playing mostly on the special teams unit.

Second, Quinn ignored the advice of a partner at his law firm and left to open a solo practice—in September 2008, as the Great Recession hit. Quinn persevered, and today the TGQ Law Firm has five attorneys in three Michigan cities. The home office is practically in the shadow of Michigan Stadium.

“I fell in love with working for myself and with estate planning,” he says. “I love knowing that I’m helping clients resolve a stressful, emotional situation.”

The TGQ Law Firm’s focus on estate law is a departure from the health care practice that dominated Quinn’s tenure at Foster, Swift, Collins & Smith PC in suburban Detroit. It’s also not the path he envisioned in law school. “Who wants to talk about what happens when people die? I thought I wanted to be Johnnie Cochran,” he says. But at Foster Swift, Quinn saw estate planning as an opportunity to expand his client base. He took the certificate program in probate and estate planning through the Institute of Continuing Legal Education, then began hosting workshops statewide. And when he decided to leave Foster Swift, he figured tying up loose ends with estate planning clients would help pay the bills until he found his next career. “I was ready to quit practicing altogether because I was so burned out.”

While he began to see appealing aspects of solo practice, hanging his shingle in the middle of a global financial crisis was nearly cataclysmic. “We lost everything,” Quinn says of himself and his family. “We struggled like crazy, yet I still loved it and never regretted my decision. But I knew I needed to make money. Every time I got ready to send off my resume, though, I’d get another big project to keep me afloat.”

All the times that Quinn hauled a projector and handouts into and out of churches, schools, and community centers—and the relationships that he cultivated along the way—began to pay off. Demographics also moved in his favor: As baby boomers grow older, about 10,000 people hit retirement age each month in Michigan alone, and the number keeps growing. They want to know they won’t leave financial chaos in their wake after they die, says Quinn. In 2015, he hired the additional attorneys, selecting his team based on their fit with his core values: treat people well, provide sound counsel, and enjoy the process. “Lawyers can be uptight,” says Quinn. “At my firm, we do things the right way, and we have fun.”

Getting to where he is now wasn’t always fun, even before those financial woes. Quinn recalls bringing homework on the road during football season, and spending the night before games studying academic subjects, not position notes.

Carr, who conducted bed checks in every room the night before a game, says having to tell a player to put away his textbooks was a bit of an anomaly. “I knew Terrence had big goals and that he’d have to work hard to achieve them. But I also knew he was a tenacious competitor on the football field and in the classroom.”

Quinn says that even during challenging times as a student-athlete, he never considered giving up—a fortitude that carried him through the difficult beginning of solo practice.

“I’ve always had to work for everything I’ve gotten. But God has a plan, and I know I’m doing the work that I’m supposed to do.”