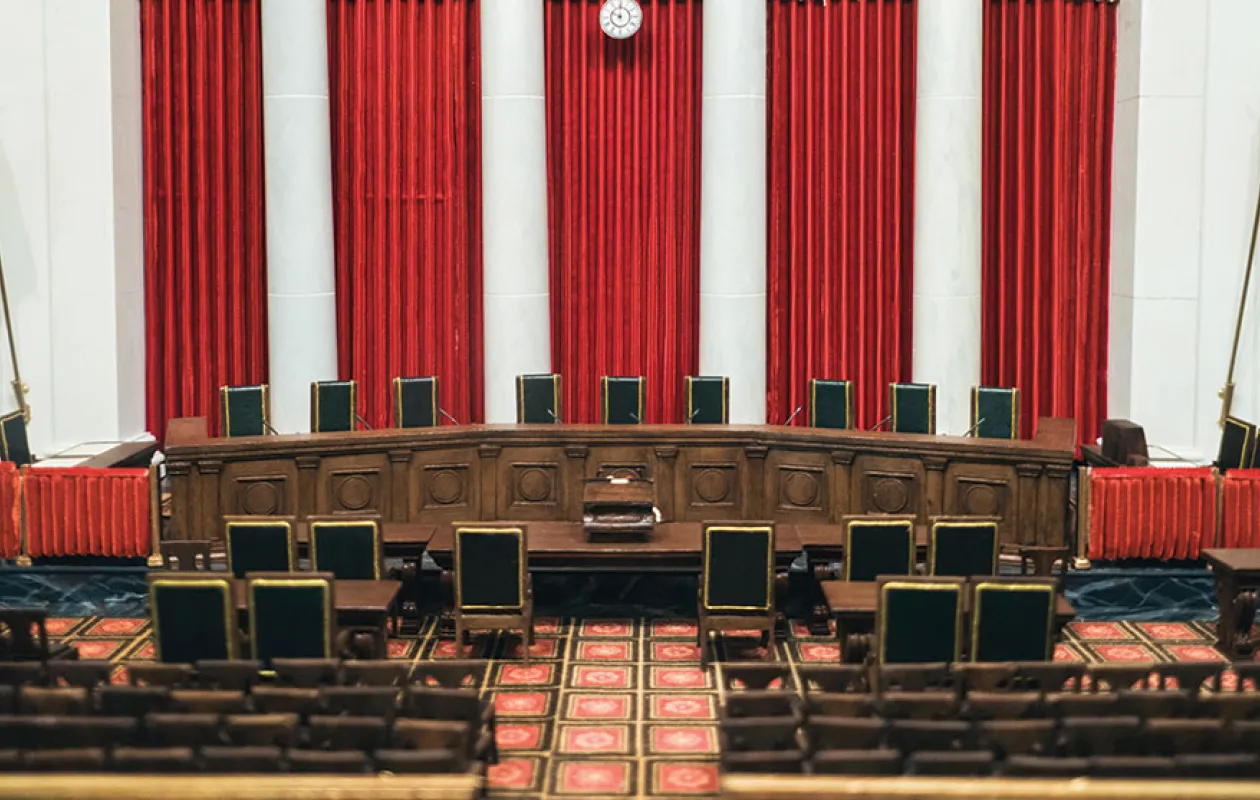

For 20 years, Jeffrey Minear’s dealings at the Supreme Court followed a familiar pattern. As a litigator in the Office of the Solicitor General (SG), he would prepare a brief, present argument, and await the ruling—a process he repeated more than 50 times. That all changed in 2006, when a straightforward, if somewhat less predictable, mandate became his daily task at the Court: perform such duties as may be assigned by the chief justice.

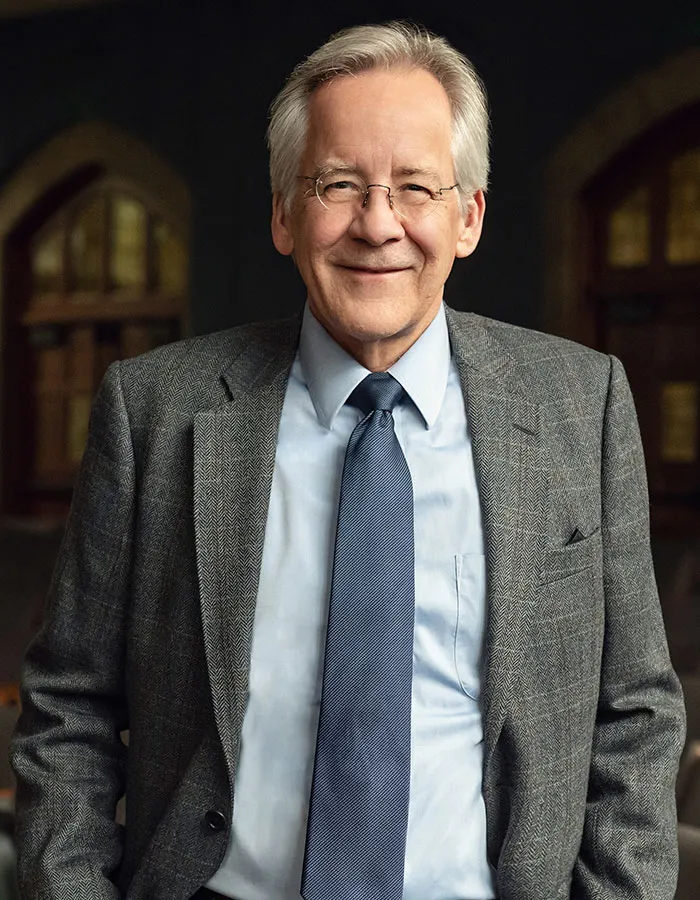

Minear, ’82, served as counselor to Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. for 16 years, until he departed the Court last October. It was a deeply varied role that provided Minear with a unique perspective into the workings of the nation’s highest court.

A Flexible Position

The 1972 law that established the counselor role at the Supreme Court devotes a mere 13 words to describing the position’s specific responsibilities. It gives the chief justice wide latitude in defining the scope of the role and associated staff. (At the time, the position was called the administrative assistant to the chief justice.)

§ 677. Administrative Assistant to the Chief Justice

(a) The Chief Justice of the United States may appoint a Counselor who shall serve at the pleasure of the Chief Justice and shall perform such duties as may be assigned to him by the Chief Justice.

Excerpt from 28 U.S. Code § 677

Then-Chief Justice Warren Burger interpreted the role as an expansive one, with the counselor overseeing a large team to assist with all of the chief’s responsibilities apart from case decision-making. his succesor, Chief Justice William Rehnquist, however, eschewed meetings and bureaucracy and vastly shrank the position and its mandate. Chief Justice Roberts chose a balance between the two extremes.

“When I came on board, the chief justice described his concept of the role as much like a chief of staff or chief operating officer,” Minear says. “I would make decisions about what the chief needed to address himself, what are things I could handle knowing he had delegated them to me, and what matters could be delegated to others.”

Collegial Working Relationships

Minear was first acquainted with Roberts when they were both in the SG’s office in the late 1980s and early 1990s. But their working relationship deepened after Roberts returned to private practice in 1993, particularly during the antitrust case United States v. Microsoft.

Minear and Roberts worked side by side in the suit against the tech giant; Minear and the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division represented federal interests while Roberts represented the interests of 19 states. Later, they found themselves on opposite sides in a Supreme Court original action involving a major boundary dispute in southeast Alaska.

“In all the work we had done, particularly in the Alaska case, there was a real commitment to moving the cases forward efficiently and professionally. The Alaska case moved much more quickly than your typical original action because we didn’t engage in contentious dilatory practices and unnecessary discovery,” Minear says. “We both were zealously representing our clients but were doing so with their interest at heart in terms of trying to reach a prompt and lasting resolution.”

New Role, New Responsibilities

Roberts reentered government service in 2003 when he was appointed to the US Court of Appeals by President George W. Bush, who nominated him to serve as chief justice two years later. A year into his term, the chief justice called Minear and asked him to serve as counselor. After more than two decades of appellate practice, the job was a significant change in responsibilities, but Minear embraced the opportunity.

“I had become very accustomed to the pace and nature of the work in the SG’s office. Working within the Court was a very different environment requiring very different skills. There was a much bigger emphasis on management and administration and dealing with a wider range of individuals than at the SG’s office. It was invigorating to exercise muscles that I hadn’t used in a while—perhaps my most relevant prior experience dated back to when I was a chemical engineer managing a workforce in a petrochemical plant,” says Minear, who spent two years working in Texas between his undergraduate studies and matriculating at the Law School.

Minear chaired a committee made up of the Court’s administrative officers—including the clerk, marshal, public information officer, and others—that are primarily tasked with the daily operations of the Court and its staff of around 500.

“All of the Court’s administrative officers and their staffs were very capable, so much of my work involved coordinating their efforts and finding opportunities for innovation, often in operations that people don’t see, such as budget, security, human resources, and information technology,” Minear says. “Everything was very much a team effort.”

Beyond serving the chief justice and managing Court operations, Minear often represented the Court to external entities. He helped coordinate the chief’s responsibilities as chancellor of the Smithsonian Institution, and he organized meetings with foreign dignitaries and informational exchanges with foreign courts. He also liaised with the legislative branch on budget issues and with the executive branch on matters related to the deaths of Justices Scalia, Stevens, and Ginsburg and the retirements of Justices Souter, Kennedy, and Breyer.

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. in a Supreme Court press release announcing Minear’s retirement“Jeff Minear has exemplified the finest tradition of Court staff, enabling the Supreme Court, and courts across our country, to serve the public efficiently and effectively. He has brought deep knowledge, outstanding judgment, and a tireless work ethic to court management and improvement. I am grateful for the many years he has served so well as my counselor and as an officer of federal judicial administration.”

Presiding Over an Impeachment

When it became clear that the US House of Representatives would vote to impeach then-PresidentTrump, Minear worked with the chief justice and others at the Court to prepare for the proceeding in the Senate. While records of the two previous presidential impeachments provided some guidelines, the Senate rules are arcane and leave room for interpretation, requiring analysis of both history and law.

Minear had the benefit of having worked on the one impeachment case that reached the Supreme Court—Nixon v. United States, which involved a judicial impeachment that raised questions about legal challenges to the congressional process. He worked closely with then-Solicitor General Ken Starr and then-deputy SG Roberts in authoring the Supreme Court brief.

“The first step in preparation was to go to the library and get the records from the prior presidential impeachments,” Minear says. “We also met with the Senate parliamentarian, who plays a critical role in all matters on the Senate floor, and we met with staff of the majority and minority leaders to discuss how they envisioned the process would go.

“It was a fascinating process. The chief justice took the view that he was the presiding officer but not the ultimate decision-maker. The Senate was acting as the jury, and his job was to make sure that the process proceeded in an orderly fashion,” Minear says. “I have to say, it was quite a unique experience.”

Atop the Judiciary

With more than 30,000 employees and a $7 billion budget, the federal judiciary is a complex institution. A large part of Minear’s role was assisting the chief justice in his capacity as the head of the judicial branch.

While each individual court is self-governing and responsible for its day-to-day operations, they collectively are subject to the rules and regulations set out by the Judicial Conference of the United States. That body, consisting of 13 chief circuit judges and an equal number of district judges, is chaired by the chief justice and meets twice a year to consider and implement policy and administrative initiatives throughout the federal judiciary.

As chair, the chief justice is the appointing authority for the more than two dozen committees that make recommendations on specific matters for the conference to consider—ranging from rules governing evidence and court procedures to ethics guidance and facilities management. Minear served as a key liaison during the appointment process and during committee deliberations.

Jeffrey Minear, ’82The chief has both an oversight role and direct involvement with committee work when there are specific issues that require his guidance. I saw my role in this area as making sure he was informed and had his finger on the pulse of what’s happening throughout the US courts

Embracing the unknown

While Minear has retired from his role at the Court, he plans to remain active in the law. Most recently, he was appointed to serve on an international arbitration panel related to a water resources dispute between India and Pakistan. The work connects him to his earlier service as an environmental lawyer at the Department of Justice in the 1980s and builds on the international ties he established through his work at the Supreme Court.

The court of arbitration, which first convened in January, was established under the Indus Water Treaty. This international agreement, reached in 1960 through negotiations between India and Pakistan facilitated by the World Bank, allocates water resources from six rivers in the Indus River Basin. The treaty gave each country control of three of the rivers, with conditions and limitations on their respective uses.

“The treaty allows India to build hydropower plants on rivers that flow into Pakistan, subject to strict conditions, and Pakistan has concerns related to certain construction and whether it will affect Pakistan’s own water development plans,” Minear says. “It’s a very interesting problem, and one that draws upon my background not only in law but in natural resources law and engineering, as well as my prior experience litigating interstate water disputes in the SG’s office.”

Serving on an international court of arbitration is not something Minear expected to be involved with, but the time was right to seize a new opportunity—something he plans to keep in mind as his career evolves. And while he is subject to the Supreme Court’s bar on former employees doing any appellate work before the Supreme Court for two years, he says it’s possible he will one day return to the Court in his capacity as an appellate lawyer.

“Who knows what the future holds, and that’s the nature of a career in law—you never know what’s around the corner,” Minear says. “You can have a very rich career in public service by taking the leap into unexpected opportunities.”