In the 2016 whistleblower case Haas v. CooperRiis, Inc., a jury in Asheville, North Carolina, awarded a $3.65 million verdict to plaintiff Laura Haas, who claimed she was fired for reporting patient neglect to the mental health company CooperRiis. It was the largest jury verdict for an individual in a wrongful termination case in North Carolina history.

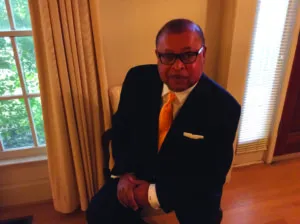

For Harold Kennedy III, who brought Haas to trial in February, it was another groundbreaking case in his legal portfolio.

Kennedy, ’77, is a partner at Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy, and Kennedy LLP in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, a family firm started by his parents. The practice, which includes Kennedy’s twin brother, Harvey, focuses on termination from employment, sexual harassment, medical malpractice, and wrongful death.

When Kennedy and his brother joined the firm in the late 1970s, they decided to focus on employment law because, as Kennedy notes, “there was a real need for lawyers, especially in the South, to take civil rights cases.”

One of his first major lawsuits was Hogan v. Forsyth Country Club Co. (1986), the first sexual harassment case in North Carolina. Kennedy’s client was a waitress at a country club who contended that she had been sexually harassed at work by the executive chef.

“We had to go to the North Carolina Court of Appeals to get the right to proceed in the case, because the country club took the position that women should not have a right to sue for sexual harassment in North Carolina,” says Kennedy, who, under North Carolina common law, sued on his client’s behalf for intentional infliction of mental and emotional distress.

“We tried the case in 1986, and the jury came back with a $900,000 verdict for our client, which was then the largest jury verdict in my county in North Carolina. The case opened the door for women throughout North Carolina to sue in state court for being sexually harassed on the job.”

Another of Kennedy’s cases that impacted North Carolina law was Amos v. Oakdale Knitting Co. (1992).

When Kennedy started practicing in 1978, employees in North Carolina could not sue for wrongful discharge in violation of public policy. That changed with Amos, when the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled in favor of Kennedy’s clients—three women who were fired from their jobs for refusing to work for less than the minimum wage.

“The court ruled that the employees had a right to sue for wrongful discharge in violation of public policy, because they said that firing an employee for refusing to work for less than the statutory minimum wage violated the public policy of North Carolina.”

Then there was Patterson v. McLean Credit Union (1989), a U.S. Supreme Court case concerning the interpretation of 42 U.S.C.S. § 1981, a civil rights statute that was passed by Congress after the Civil War.

In Patterson, the Supreme Court unanimously held that it would not overrule its prior precedents that prohibited racial discrimination in the making and enforcement of private contracts.

However, in a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that 42 U.S.C.S. § 1981 did not apply to racial harassment on the job, but only applied to the formation of a contract.

The Patterson case is one of several that led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which broadened the legal remedies available to victims of employment discrimination.

Under that act, victims of racial harassment on the job now can sue for damages. Kennedy was part of a team of attorneys that represented appellant Brenda Patterson before the Supreme Court.

Kennedy is humble about his legal victories but admits it’s thrilling when a jury returns with a large verdict.

“It has to be one of the most exciting days in one’s practice,” he says. He cites an interest in helping people get justice, especially those who have been wronged in some way by big corporations and the government, as motivation for his work.

Also influential have been his parents—dad, Harold Kennedy Jr., who practiced law until his death in 2005, and his mom, Annie, who is now 92.

“My brother and I learned a great deal about being good lawyers, especially in the early years, by practicing with our parents,” Kennedy says. “Working with them every day was a real honor.”