The year 1986 was momentous in Philippine history as the People Power Revolution brought new hopes for freedom and democracy.

Raphael Lotilla, LLM ’87, had a front-row seat to the seismic shifts in government and society that were then underway. As a young law professor at the University of the Philippines, he was involved in studies the university was conducting on a new constitution.

But he faced a tough decision: stay home and help continue the march toward democracy or travel thousands of miles away to study at Michigan Law.

“The new government of President Corazon Aquino had just started, and there was a commission organized in order to draft a new constitution,” says Lotilla. “So it wasn’t really in my immediate plans to go to the United States to take up my master of laws.”

However, he was encouraged to further his studies by two trusted mentors: Irene Cortes, LLM ’56, SJD ’66, a former dean of the University of the Philippines College of Law who later became a Supreme Court justice, and Edgardo Angara, LLM ’64, at the time the president of the university and a future senator.

“He felt that it would be good exposure to different legal systems,” says Lotilla. “He told me, ‘When you come back, the problems of the country will still be here.’”

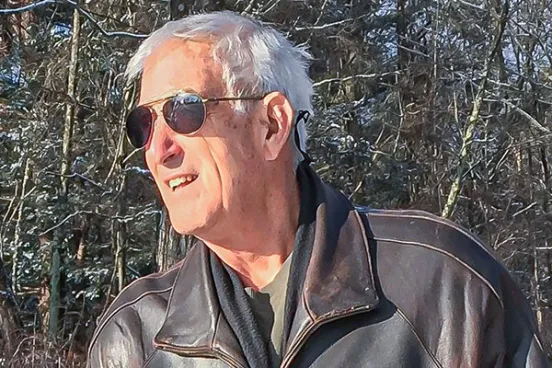

When he returned from Ann Arbor, Lotilla resumed teaching and became more directly involved in government work over the course of his career. He would go on to serve under four presidents, including current President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., and ascend to the position of secretary of energy not once, but twice.

Raphael Lotilla, LLM ’87“Some things you never plan for. What I was certain about was that I was going to do my best in whatever I do... And that's for the benefit of my country and our people.”

More than keeping the lights on

Lotilla was appointed to the position for the second time in July 2022, and he reassumed the role during a period of significant challenges: righting the privatization of the energy sector, confronting climate change, and addressing poverty.

When he was energy secretary from 2005 to 2007, his main objectives were to see through the privatization of government-owned assets in an effort to make the energy sector more market determined.

“The power assets were in the hands of the government,” he says. “The national power corporation owned the dams and almost all of the major power plants in the country. It owned and ran the transmission system and had a very heavy influence on the electric cooperatives and distribution with utilities.”

He was involved in drafting and negotiating the law that provided the framework for reform and privatization. However, during the subsequent 15 years—when he had left government—the scales tipped in the other direction; a private vendor now has a monopoly in running the government’s transmission assets.

“It’s apparent that certain distortions have occurred, departures from the original plans that we had,” Lotilla says. “So now we’re trying to address a number of them, like issues involving promotion of competition; a better implementation of the market mechanisms; and ensuring that the monopolies, the public utilities that are regulated entities, are properly guided by government policy.”

While it was clear during Lotilla’s first stint as energy secretary that cleaner energy sources were needed, the global challenges of climate change have taken on more urgency in the years since. The Philippines—which has made a smaller contribution to climate change compared with larger, industrialized countries—is trying to balance its responsibility to transition to low-carbon sources of energy while acknowledging the difficulties of doing so as a developing country.

“Our problem is one of poverty, not only economic poverty, but energy poverty—that is, people’s lack of access to a clean and stable supply of power. There has been a lot of reliance, for example, on cooking firewood. Of course, now we’re more conscious about not only the effects on the climate, but also on the health of people. That said, how do we provide cheap power that will enable economic development in the country? Because the main concern is to address poverty.”

The challenges are not only economic. The Philippines is an archipelago that consists of thousands of islands—submarine cables are required to connect communities to the energy grid—and typhoons are striking with greater frequency.

Lotilla did not anticipate being in this position when he started his career. “I never planned to be in the energy sector,” he says. “But I guess that’s what legal education prepares you for. You’re prepared to go into anything.”

Coming to Michigan Law

When Lotilla arrived at U-M to start his legal education, he was the latest in a long line of Filipino students who were recipients of the DeWitt Scholarship. A gift from 1908 graduate Clyde Alton DeWitt, the scholarship supports law students from the Philippines, where DeWitt founded a law firm. Recipients include Lotilla’s mentors Irene Cortes and Edgardo Angara as well as former Sen. Miriam Defensor Santiago, LLM ’75, SJD ’76.

George Malcolm, 1906, is another example of the deep ties between Ann Arbor and the legal system in the Philippines—he founded the University of the Philippines College of Law and served as a justice on that country’s Supreme Court during the American occupation.

“It’s people like DeWitt and Malcolm who established a very close relationship between the Philippines and the University of Michigan,” Lotilla says.

Lotilla threw himself into his studies at Michigan Law and still remembers two influential faculty members—Bruno Simma, who became a member of the International Court of Justice, and Peter Behrens, a visiting professor from the Max Planck Institute. Lotilla’s research focused on selected disengagement of foreign debts and helped him better understand the debts the Philippines had incurred to foreign governments.

He also was fascinated by extensive discussions under Donald Regan, the William W. Bishop Jr. Collegiate Professor of Law, of Marbury v. Madison and the Interstate Commerce Clause, which allows the federal government to legislate on issues that affect commerce throughout the United States.

“The Philippines is a unitary system,” says Lotilla. “So there is an analogy between the Interstate Commerce Clause and the need for a similar mechanism in the Philippines in order to prevent one local government from holding hostage activities affecting the economy of the country.”

A varied professional journey

After receiving his LLM, Lotilla returned to his home country and continued to teach at the University of the Philippines. He also served as a legal consultant and adviser to Philippine senators and the country’s National Economic Development Authority (NEDA).

In 1996, he became undersecretary and deputy director-general of NEDA, a cabinet-level body focused on economic planning, where he supported efforts to liberalize the Philippine economy and enable greater competition. He left in 2004 to serve as president and CEO at the Power Sector Assets and Liabilities Management Corporation, a state-owned corporation tasked with managing the privatization of power assets, among other things. A year later, he was asked to become energy secretary for the first time under President Gloria Arroyo.

After his first term as energy secretary, he took a break from government and headed a regional project funded by the Global Environment Facility on the sustainable development of the East Asia seas before joining the private sector.

It was during that tenure, in 2012, that he was nominated to be chief justice of the Supreme Court, an honor that he declined due to his belief that, in the Philippine context, the position should go to the most senior associate justice. In the end, a fellow graduate of Michigan Law, Maria Lourdes Sereno, LLM ’93, was appointed chief justice.

Lotilla has traveled a long road spanning academia and government service, and while it’s one he hadn’t mapped out at the start of this career, he’s found it fulfilling to serve in both capacities.

“Some things you never plan for. What I was certain about was that I was going to do my best in whatever I do,” Lotilla says. “And that's for the benefit of my country and our people.”