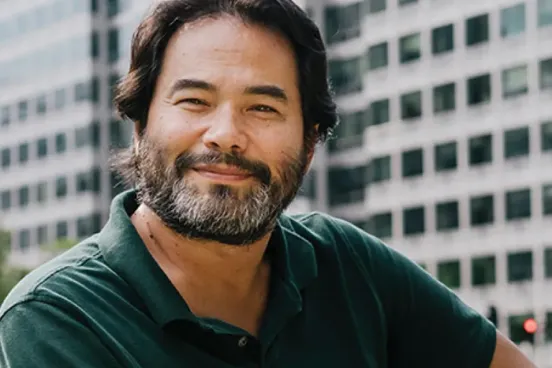

When he was considering becoming the first general counsel of the newly opened Office of the Inspector General for the New York City Police Department (OIG-NYPD) in 2014, Asim Rehman, ’01, wasn’t sure what to expect when discussing the job offer with his mom, dad, and boss.

He was convinced that his parents, immigrants from Pakistan, would question leaving the comforts of his private-sector job at MetLife for one in government. Instead, “Without hesitation, they told me to take the job.”

Next, after making the decision, he went to his supervisor at MetLife. “Midway through my lengthy explanation of why I was leaving, she cut me off and said, ‘Asim, when you get an offer like this, you don’t pass it up.’”

Rehman, who helps oversee the nation’s largest municipal police department, was promoted to first deputy inspector general in 2017. As part of the Department of Investigation—New York City’s independent corruption watchdog—his office investigates and reviews systemic issues concerning the policies and practices of the NYPD.

His team has released 15 reports on a variety of topics regarding New York policing, from the treatment of the LGBT community to officer use of force to body-worn cameras. After Eric Garner died in a 2014 police incident, Rehman’s department investigated the use of chokeholds by NYPD officers, looking at several cases where officers applied chokeholds and how the officers were disciplined. “We were able to educate the public on NYPD’s policy on chokeholds, the trends in chokehold cases, and what that tells us about things the police department should be doing differently,” Rehman says.

How does one go from working as corporate counsel at MetLife—where he provided global litigation support to more than 40 foreign MetLife companies—to overseeing the NYPD?

“I was working on police accountability issues because they were important to me, not because I was looking for a job,” Rehman says.

A self-described corporate litigator by day and community advocate by night, Rehman co-founded the Muslim Bar Association of New York in 2006. He advised community members of their legal rights and employers on accommodating workers who must fast during Ramadan. When the local Muslim community raised concerns about police surveillance issues, Rehman dove in. Later, when New York City legislation was enacted in 2013 establishing the Inspector General’s office, local civil rights attorneys suggested Rehman apply for the open general counsel position.

“I was encouraged that my peers came to me with that idea, and saw this as an opportunity to work full time on an issue that mattered to me,” he says.

There are some parallels between Rehman’s current work and his previous role.

“As an in-house lawyer, the work is sometimes less about the law and more about assessing risk and identifying solutions.” He says his work at OIG-NYPD, like that at MetLife, “involves bringing the legal voice to the table when people are thinking about issues from other perspectives.”

However, with police conduct under intense public scrutiny, there is an acute onus on Rehman and OIG-NYPD’s team of 35 people to produce exceptionally high-quality reports that are rooted in fact and provide reasonable, actionable recommendations.

“We’re not against the police. We are in favor of a successful police department. Our belief is that to do that you need transparency, accountability, and an outside voice,” he says.

Across the 15 reports his office has released, NYPD has implemented or accepted approximately 75 percent of the reports’ recommendations for reform. Beyond New York City, Rehman adds, “We are very proud that our office’s reports have been recognized by other police oversight entities as best practices in the field.”

This work is an extension of his experiences at Michigan Law. In his first year, Rehman helped with an asylum case and was taken aback at how aggressively the government interrogated his client. “Here is someone who has gone through hell and back to escape his country, and now he’s being painted on the stand as fabricating this entire story.”

After court, Rehman returned to campus, changed out of his suit, and reflected on the comforts in his life compared to his client’s. Sitting in Constitutional Law that afternoon, Rehman couldn’t stop thinking about his client, and how far removed his situation was from the intellectual discussion in the classroom.

“That experience in the Law School clinic showed me how easy it is for lawyers to focus on concepts and ideas, when the reality is that the laws that we deal with impact the lives of real people.” Rehman carries this mentality with him at OIG-NYPD.

“Some of our work may sound heavy on policy, but at the end of the day we are dealing with a police department that encounters the public on a regular basis,” he says of his office’s reports. “The change we are trying to make ultimately affects the lives of people.”