Hungary, after lining 109 miles of its border with razor wire, passed a law requiring asylum-seekers to remain in camps constructed from shipping containers while their cases are reviewed—a process that could take years. Human rights groups condemned the action, but does it violate international law?

Kenya has hosted the world’s largest refugee camp since neighboring Somalia destabilized in the early 1990s. The government wants to close the camp and send its 260,000 denizens home. But is drought-afflicted Somalia obligated to accept them?

These are just some of the legal questions confronting states and international bodies at a time when the UN estimates 34,000 people flee their homes every day because of war or persecution. And these particular conundrums involve an especially tricky area of international law: refugees’ freedom of movement—the topic of the Colloquium on Challenges in International Refugee Law, which was hosted in the spring by Michigan Law’s Program in Refugee and Asylum Law (PRAL).

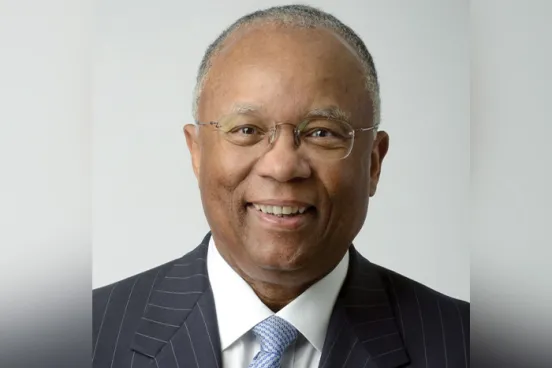

“These are the cutting-edge issues that governments, NGOs, and refugees are worried about,” says James C. Hathaway, the James E. and Sarah A. Degan Professor of Law and director of the PRAL. “We’re not lawmakers, but our goal is to help make the debate more informed and thoughtful.”

Each colloquium, held on a nearly biennial basis since 1999, has added to a set of recommendations known as the Michigan Guidelines on the International Protection of Refugees.

The guidelines deal with the interpretation of international treaties and agreements such as the 1951 Refugee Convention and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The 2017 colloquium has added the Michigan Guidelines on Refugee Freedom of Movement to the repository, which is part of the Michigan Journal of International Law.

“The Michigan Guidelines have been picked up by courts around the world,” says Nora Markard, a professor at the University of Hamburg who was one of 10 international experts invited to participate in this year’s colloquium, along with Michigan Law students. “This effort brings together people from different regions in the world, both academics and practitioners from high levels, and the guidelines are a really important set of standards.”

The face-to-face portion of the colloquium took place over three intense days in the Lawyers Club Lounge. While arguments grew heated at times, Hathaway says, they also were productive.

Credit is due in large part to the students, he adds, noting that each set of Michigan Guidelines is the product of a two-year process that begins with a team of students conducting intensive research more than 18 months before colloquium participants meet in person. The meeting itself is intimate and collegial, an atmosphere that facilitates a productive discussion.

“The informal format, with so few participants, means you’re more likely to get down and deep into the particular issues that are being discussed,” says Justice Susan Glazebrook, who has sat on New Zealand’s Supreme Court since 2012 and has decided several cases involving asylum-seekers.

Like past guidelines, the Michigan Guidelines on Refugee Freedom of Movement may inform myriad pending cases, helping to clarify refugees’ rights and nations’ obligations as mass displacement in the Middle East and Africa clashes with resurgent nationalism in the West.

“Countries are saying, ‘We’re full; we have too many people already, and we can’t let any more in,’” says Markard. “Border regimes are tightening, and it’s on the backs of refugees and their families. It’s so politically fraught—and that’s why it’s important to get the message out about what the legal standards actually are.”