Harvey J. Shulman, ’72, read a letter one morning pleading for a litigator to fight against renewal of a Michigan television station’s license, saying its owner used news blackouts and manipulations for his personal and political gain.

Shulman sat in his ramshackle office in Washington, D.C., transfixed by the accusations from the Lansing branch of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). They were accompanied by my exposé of WJIM-TV and owner Harold (Hal) F. Gross, which splashed a few days earlier across the top of the Sunday front page of the Detroit Free Press.

“I just couldn’t believe a broadcaster could get away with this for so many years,” Shulman recalled recently at his winter home, a Phoenix condo that he shares with Eric Mugele, a corporate training and development executive who has been his partner since 1987.

The smart move back in 1973 would have been to send the ACLU letter back. Shulman was no litigator. He had never even appeared in court as a lawyer, had never deposed a witness. Shulman, who skipped fourth and eighth grades, was just 24. He had earned his Michigan Law degree only 16 months earlier.

Besides, there was no money to mount a challenge. The Media Access Project, a lightly funded public interest law firm in Washington, paid Shulman just enough to scrape by. The ACLU branch members were working folk. On the other side, WJIM-TV was immensely profitable. In 1954, a Federal Communications Commission (FCC) report showed that the station counted as pretax profit an eye-popping 90 cents out of each dollar of revenue. Even in 1973, Gross Telecasting’s profit margins were well above broadcast industry averages.

Despite these and other formidable obstacles, Shulman packed interns and duffle bags into his yellow Dodge Dart and left the nation’s capital for Michigan’s.

For months, they camped out in a downtown hole in the wall, relying on the kindness of ACLU members for casseroles, sandwiches, and the occasional hot meal in someone’s home. They interviewed people Gross had attacked or blacked out, including the owner of the Lansing Tennis Club, which owed $1,500 for advertising, and Lansing Mayor Jerry Graves. Gross had ordered that Graves only appear in the news when it made the mayor look bad.

To back my story, I relied on dozens of interviews with former station employees, as well as a clutch of memos ordering news blackouts and manipulations. In response, the local paper ran a front-page story that I was under police investigation for supposedly burglarizing Country House, the WJIM studios with richly paneled executive offices and a swimming pool out back. Employees gave me the memos, which had been posted over the years on the newsroom wall.

In taking on Gross’s media empire, Shulman faced off against veteran litigators and defeated their efforts at summary dismissal. Over the next decade, testimony was taken from 129 witnesses during 164 days of hearings, producing 24,355 pages of transcript and 917 exhibits.

The beginner won. It was a stunning victory that no one expected, least of all Hal Gross and Harvey Shulman.

The case was “unique, massive, and complex,” administrative law judge Byron E. Harrison wrote in a 249-page opinion in 1981, finding overwhelming evidence of “clear intent” to engage in “outright fraud.” He held that Gross was “beyond rehabilitation.” The FCC later softened the decision, awarding a two-year “short license” instead of the normal three, a signal to Gross to sell.

Lawyers in Motion Stay in Motion

Shulman credits his success, in part, to Michigan Law’s willingness to take a gamble on him. At age 16, he graduated from Brooklyn Tech High School, where 6,000 students attended. He was just 19 when Michigan Law accepted him, a risky move not just because of his age but because his bachelor’s degree from the University of Maryland was in physics, an uncommon preparation for a legal career.

In high school, Shulman struggled with physics because it made no sense to him. But after he mastered the subject, he came in first among a thousand students taking a physics exam.

A key turn in his law school experience came when he took Professor Arthur R. Miller for Civil Procedure.

“Some people came out of that first class terrified” by Miller’s famously demanding questions, which seemed to flow to those least prepared to answer, Shulman recalls. “I knew I would do just fine if I was thoroughly prepared, and being too young to drink, I spent Friday and Saturday nights in the Law Library studying.”

Shulman wanted to be an environmental lawyer. He spent a semester of law school in Washington, D.C., where he expected to work on pollution issues. Instead, he was assigned to handle FCC issues at the Center for Law & Social Policy because he was the only law student who knew physics—a possibly valuable asset in radio and television broadcast cases.

While Shulman mastered the art of preparing for class, he says he had no clue about how grades and connections got one onto the Michigan Law Review, which could open doors to the best-paying jobs. But looking back, Shulman says he’s glad he sought jobs he wanted, not the biggest paycheck.

“Take a job based on what is emotionally and intellectually satisfying, not what pays the most, and you will have a much happier life,” he says. “You don’t have to live in one place; you don’t have to do one thing if you practice law.

“Never feel intimidated, and remember that lots of hard work makes up for inexperience,” he adds. “And when you know enough that you can take responsibility for the growth of younger people, empower them to grow and to be both fearless and passionate.”

Shulman took his own advice while still a young lawyer himself.

Howard Weiss, a law student at The George Washington University when he joined Shulman’s litigation team, recalls working for him as a great learning adventure, although it distressed his girlfriend at the time. Weiss did legal research on how to frame the WJIM license challenge and push back against efforts to limit discovery.

“Harvey’s a good man and brilliant lawyer,” Weiss says. “He was hard to please because he has a steel-trap brain and he never forgets anything. My girlfriend said I was out of my mind because I was working so hard and making maybe $3.50 an hour when a law firm would pay me $8. I told her I thought we were doing the Lord’s work.”

Jim Backstrum, a student at the University of Pennsylvania Law School who later became a Justice Department senior lawyer, says, “I would have been happy just to carry Harvey’s bags for him.” When he arrived in Lansing, he expected their little band of lawyers to be sent packing quickly.

“We were taking on Leo Farhat, a locally famous lawyer, and Arent Fox, a big D.C. firm with former FCC people, and I knew right off Harvey had no litigation experience,” Backstrum recalls. “I figured we would get hometowned. But the raw intelligence of this brainiac and his determination kept it all afloat. His energy level was mind-boggling. His commitment to the ideals we were fighting for was fantastic.”

The one thing the team did not like was Shulman taking the wheel of his yellow Dodge Dart as they drove all over the Midwest, cajoling former employees who had gone on to other stations into giving affidavits. Finding Shulman’s driving not so smart, they made sure Karen Tomb—the team’s hardworking paralegal whose own path to law school was inspired by the case—was more often behind the wheel.

A Not-Bigger, Not-Older Rookie

Backstrum’s detailed analysis of advertising records showed years of fraudulent billing. Gross would run local commercials, but also bill CBS for network commercials that never aired. The station even had a fake CBS eye logo. To save money, Gross had the 11 p.m. weather forecast taped hours earlier with no updates when unexpected ice storms and other changes threatened lives.

Farhat, a former Golden Gloves boxer whom I found to be alternatively pugnacious and gracious as I covered the story, quickly learned to respect Shulman.

“When we arrived in Lansing, we had no idea who Farhat was,” Shulman says. “He was gruff and tough, the opposite of a K Street or Wall Street lawyer in appearance and demeanor. Leo could be a nice guy, and at times he could scream at you—the theatrics of the job. And me, I was maybe 18 months out of law school when I examined my first witness. I’d never tried a case or deposed a witness, but nothing phased me. What I did was watch every move Leo made. I learned a lot about how to handle witnesses.”

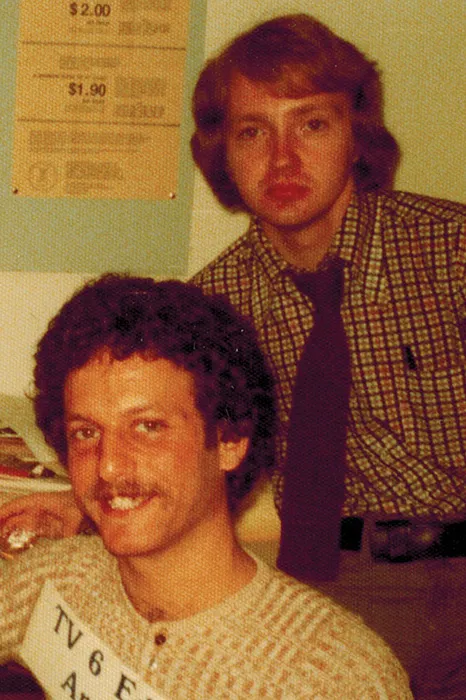

Shulman realized how much he had impressed Farhat only when it came time to meet Hal Gross for a deposition. Gross, a former haberdasher, stood six-foot-four in his tailored suits. Depending on your point of view, he was either courtly or imperious. Gross looked down at Shulman, a skinny guy with a mop of wiry hair who barely came up to his neck, and put his hand out to shake.

“Oh, I pictured you to be somebody totally different—bigger, much older,” Gross said, subtly revealing that Farhat had prepared him to expect a tough line of questioning by someone who knew what he was doing.

Shulman also drew on advice he got while clerking for the Hon. Frank Coffin, then chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit.

Judge Coffin told Shulman, “we get lots of appeals, but what we get is just a record. In your briefs, you’ve really got to get to the judge. You have to make your case real—about people or something that makes a judge want to care.”

At every turn, Shulman tried to make the WJIM case about the people who had been ordered to act illegally or unethically—about how they did what they were told just to keep their jobs—and also about the victims of the news distortion and blackout orders.

“What I learned from working with Judge Coffin is that you use all the legal tools you have, not just the ones you want, if you are going to win,” Shulman recalls. “One thing we had going for us was that the FCC had previously admonished Gross for a lengthy editorial attacking a state government official.”

Indeed, the editorial had taken up about half the nightly newscast, berating a little-known state aviation official who would not give Gross the lease terms he wanted for an airport restaurant.

“The legal principle is that station owners are trustees using the public airwaves for the public interest, convenience, and necessity, not to punish enemies, promote friends, and pursue their personal financial interests,” Shulman says.

“Ain’t American Justice Great.”

WJIM turned out to be just the first of several Shulman cases I reported on over the years in the Los Angeles Times and The New York Times. Shulman has testified before Congress more than a dozen times.

In one case, Shulman fought against a tax rule sponsored by Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan [D-NY] as a favor to IBM. It was supposed to raise $12 million annually through higher taxes paid by freelance software programmers who supposedly fudged on their income tax returns. A subsequent study showed it had no such effect. Shulman represented jobs brokers for these freelancers who found the rule onerous. When he took the government to court, warning of the anger it generated, the Justice Department took action that seemed to clearly violate the law.

In 1995, I arranged a photograph in The New York Times showing Shulman and another lawyer in a Washington law office posed at a conference table with 32 complete tax returns arrayed before them. The Justice Department had turned those tax returns over to Shulman even though Section 6103 of the Internal Revenue Code makes all taxpayer information confidential.

Fifteen years later, a Texas software writer blamed his frustration over that law for his decision to fly his private plane into an Austin office building, killing Vernon Hunter, a veteran IRS worker. That law remains on the books.

Shulman was a partner at two law firms, first the now-defunct Ginsburg, Feldman and Bress and later Greenberg Traurig LLP. He helped create an association of software job brokers and served as their general counsel. He also served as general counsel of a high-tech firm founded by one of his two younger brothers. And he taught for a year at the University of Oregon Law School. Today, Shulman continues representing entrepreneurs and takes on pro bono work for grassroots organizations. He also serves on the planning commission in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. His business card and email signature say “expert advice.”

Shulman’s eye for spotting issues pre-dates his legal career, however. It traces back to when he was on the University of Maryland’s Student Government Cabinet Association in 1968. The cheerleading squad asked for its annual allotment of funds.

Shulman, noting that the university had just fielded its first black basketball player, asked why there were no black cheerleaders.

“I asked what I thought was an obvious question,” Shulman says. “I was told, by a young woman, that blacks move differently than whites.”

Shulman was gobsmacked by that response. Then came the second explanation: Black students did not belong to sororities and fraternities, so they could not travel with the teams because they often stayed at Greek houses in the still-segregated South.

The absurdity of those answers stayed with Shulman and helped frame his thinking in the WJIM case and many others where nonsense often justifies existing policy.

The WJIM case settled in 1984, more than a decade after Shulman read the letter from the ACLU and the first in my series of Free Press exposés. Gross sold WJIM-TV and five other stations in Lansing and Eau Claire, Wisconsin, for $48 million (roughly $111 million in today’s money), a steep discount from the stations’ value had the FCC license been fully renewed.

Mayor Graves, before he died, told me he was glad Gross was out, but he was not entirely happy with the result—much as he praised Shulman’s young team for winning a case he thought would go nowhere.

“So Hal Gross committed every single act the Free Press accused him of and more, and his punishment is he gets $48 million,” Graves said, breaking into a laugh. “Ain’t American justice great.”

As part of the settlement, Gross Telecasting donated $800,000 to the ACLU Lansing branch, a fund that has grown to nearly $2 million to finance defense of constitutional rights in the state capital area.

It was the only time in American history that a broadcast chain was forced off the air over news manipulations and blackouts. For decades, I’ve dined out on the story I broke, but what made the real difference in forcing Gross Telecasting out of business was not my work, but that of a wiry and determined novice lawyer named Harvey Shulman—whose career shows what a solid education and fierce determination can achieve.

In 1973, as the first investigative reporter in the Lansing bureau of the Detroit Free Press, David Cay Johnston broke the story concerning news manipulation at WJIM-TV. He went on to write for the Los Angeles Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and The New York Times.

Johnston received the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Beat Reporting for exposing loopholes and inequalities in the U.S. tax code. He is a frequent commentator in print and broadcast media and is the author of New York Times bestsellers Perfectly Legal, Free Lunch, and The Making of Donald Trump, now in 10 languages.

For eight years he taught property, tax, and the regulatory law of the ancient world at Syracuse University College of Law.