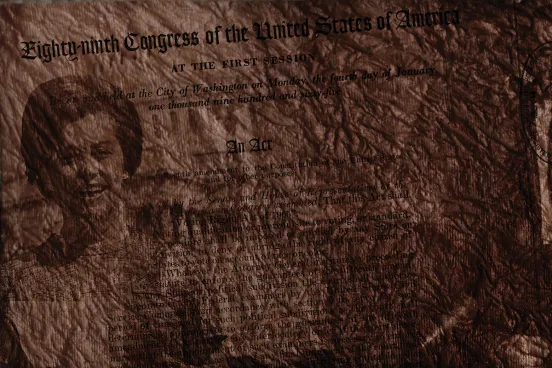

Just over 50 years ago, in February 1964, a great debate was taking place on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. Up for a vote was President Lyndon Johnson’s signature legislation, now universally referred to as the “landmark” Civil Rights Act of 1964. All eyes were on one legislator: the woman representative from Detroit, Michigan.

Her name was Martha Griffiths. And she was about to reach what has been recognized ever since as the pinnacle of her long, pioneering, and distinguished political career.

If passed, the sweeping law would prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, or religion in voting; access to public education, employment, and public accommodations; and in federally assisted programs. Passage seemed certain in the chamber, then controlled by Democrats, but a few legislators on both sides of the aisle, Griffiths chief among them, wanted to add an amendment.

They wanted to add the word “sex” to the proposed bill, thus ensuring protection for women. The idea was controversial, and even President Johnson was worried that adding the word would doom the entire bill.

If that weren’t bad enough, legislators against the amendment were making fun of it, saying its proposed addition was nothing more than a joke.

Already, opponents of the bill itself had stalled for days, proposing a slew of amendments. “We sat for hours, day after day, while one amendment after another was offered, debated, and defeated,” Griffiths, ’40, wrote many years later in a never-published autobiography. “…During the debate there had been little if any laughter. No jokes had been uttered.” But once the sex amendment was offered by Rep. Howard W. Smith of Virginia, “the House broke into guffaws of laughter.

“Various women arose to speak for the amendment, and with each argument advanced, the men in the House laughed harder. Lee Sullivan of Missouri and Edna Kelly of New York were sitting in front of me. Lee turned around and in a woebegone voice said, ‘Martha, if you can’t stop them from laughing, you simply do not have a chance.’

“I answered, ‘I’ll stop them.’

“When I arose, I began by saying, ‘I presume that if there had been any necessity to point out that women were a second-class sex, the laughter would have proved it.’ There was no further laughter.”

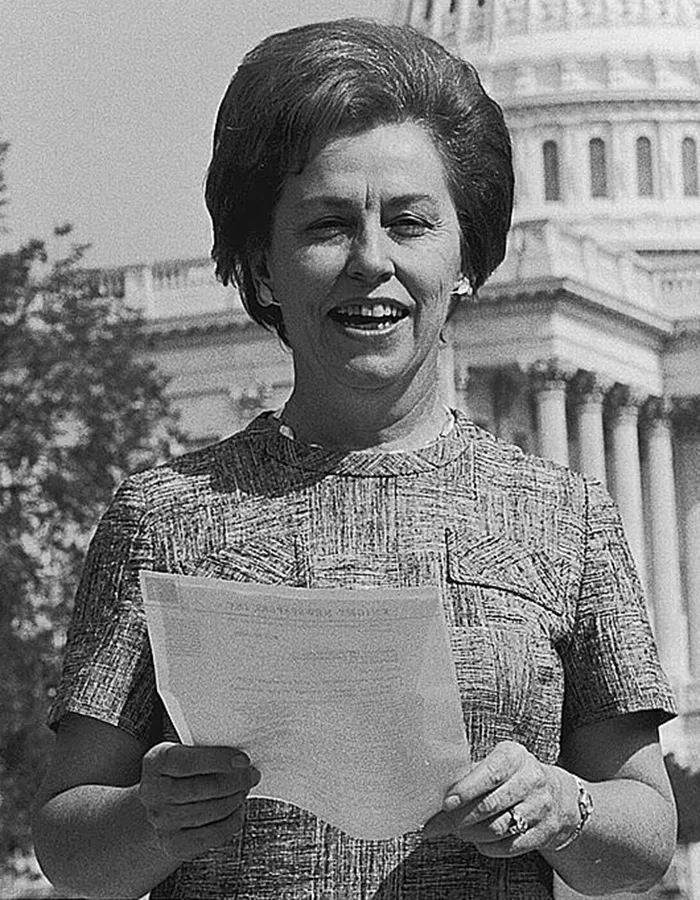

That the laughing stopped instantly is no surprise to anyone who knew Griffiths, then in her 10th year as a representative, and anyone who knew her thereafter. You took on Griffiths at your peril. Known for her blunt one-liners and shot-put

questions, not to mention her intelligence, practicality, passion, and independence, Griffiths was formidable in any context, and already had made her mark in many ways.

But this day, this speech, was destined to be her crowning achievement. As then-Washington journalist James Robinson later wrote of her remarks that day, “The House sat silent for 20 minutes. Not a single male lawyer arose to challenge the lady’s legal brief.”

From that moment, it was all Martha. And it was history.

“You are going, also.”

Technically, it’s accurate to say Griffiths’s path to that day in the U.S. House of Representatives began in Pierce City, Missouri, where she was born in 1912. But practically speaking, that path began in 1937, at Michigan Law.

That year, Griffiths and her young husband, Hicks, two fresh graduates of the University of Missouri, decided they wanted to become lawyers. Both had been top students, so they applied to Harvard Law School. Hicks was accepted, but Martha was rejected—not because she wasn’t qualified, but because she was a woman (women were first accepted at Harvard Law in 1950).

Hicks easily could have gone ahead with the Harvard path, and Martha would have made the best of it. But he refused to accept discrimination against his wife. He told her, “We will find another school,” Martha wrote in her autobiography. “You are going, also.”

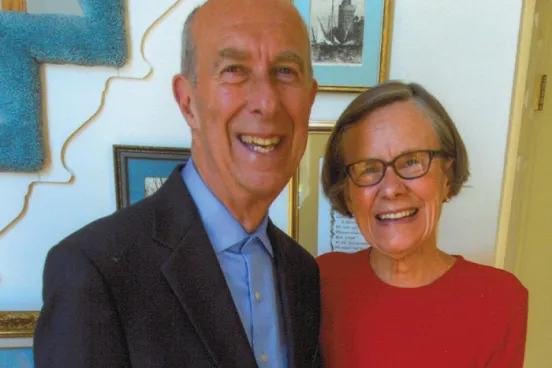

Harvard’s loss was U-M’s gain, and with it came some records. The Griffithses were the first married couple ever admitted to Michigan Law, and the first such couple to graduate, three years later, in 1940.

As remarkable as all of that was, it was just the beginning of the extraordinary life and career of the Griffithses, especially Martha, whose path was far more public than that of Hicks. He was a mentor and supporter of his wife, and he worked as a lawyer in Detroit. The result was that Martha became the state of Michigan’s most famous woman, a national figure in the women’s rights movement, and arguably the most famous female legislator in the U.S. House of Representatives at the time.

“Martha Griffiths was in the forefront in the crusade to get equality across the board for women, whether it was economical, political, or social,” President Gerald Ford told Michigan History Magazine in 2002. He had served with her as a member of Congress. “She was smart, she knew the rules, and she had deep convictions.

“She was highly respected by the Democrats,” Ford continued, “and she had many, many good friends on the Republican side, including me. She was very knowledgeable. She was a liberal and favored a liberal agenda. But on things that were not partisan, she was an excellent person to work with.”

In Class and On the Job

In her autobiography, Martha did not elaborate a lot on the couple’s time in Ann Arbor, but she did share some things about their daily life there. Hicks went ahead of Martha to find a place to live, and “when I arrived in Michigan, Hicks had already found a job at the library, and a small apartment where he could tend the furnace for part of the rent.”

Martha, meanwhile, got a job taking care of a small child for a time, and then worked at the Mary Lee Candy Shop. She wrote that she worked 54 hours a week for $9.40. “Believe me,” she wrote, “if I had been working there at the time of the Flint sit-down strikes, I would have sat down, too. Every girl working there, but two, had college educations, and we might as well have been paving streets. The work was exhausting…”. She also worked at the Michigan Law Review during the school term and at the U-M Hospital during summer, she wrote.

Martha and Hicks had been famous at the University of Missouri for their sharp debates against one another in classes (in fact, Hicks later said, the only way to resolve their debates was to get married). In a foreword to the unpublished autobiography, Hicks wrote of Michigan Law: “As law students, we worked to refine our persuasive efforts to help settle our confrontational solutions involving not only our country’s problems, but the world’s. Occasionally, we’d exchange briefs to support our positions.

“After attending a few law class sessions, we agreed without dissent to stop attending the same classes. We had quickly learned that our professors would invariably call on each of us in succession to interpret, review, and expound on the decisions in the class under consideration.

“The professors were less concerned with the wisdom and legal reasoning of the judges in the cases under review. What they were after primarily was our own personal differences of opinion for their and the students’ entertainment.”

After earning their degrees, the Griffithses eventually got involved in reforming the Michigan Democratic Party, and opened a law office with a third lawyer by the name of G. Mennen Williams—who would be elected, with the substantial help of the Griffithses, Michigan governor in 1948.

Martha was encouraged in 1946 by a suffragette to run for the Michigan Legislature. A surprised Martha declined—until Hicks told her she was running. She did, lost, ran again, and won in 1948, then served two terms. In 1952, she ran for the U.S. House representing Michigan’s 17th District encompassing Detroit; she lost but ran again and won in 1954, becoming just the second Michigan woman to serve in that chamber. She served in the House until 1974 and during that time was the first woman to serve on the powerful Ways and Means Committee. She also was ahead of her time, pushing legislation that advocated recycling, pension reform (to the ire of labor unions), Social Security benefits, and welfare reform.

But none of these accomplishments compared in drama, and historic impact, to that moment Martha stood up to silence her jeering colleagues during that Civil Rights Act amendment debate.

Her description of this scene in her autobiography has never been published. She devoted an entire chapter to the Civil Rights Act, which, she wrote, “was a bill designed primarily to give employment rights to blacks, although it did state that employers could not discriminate on the basis of race, creed, or national origin… . I was for the bill. I had known too many qualified black people who never had a chance to have a decent job simply because they were black.

“But as a woman, this bill presented many problems that apparently no one else saw at all. If the bill applied to black women, it was going to give them rights that no white woman had ever had. There were innumerable jobs that were not open to white women; and their applications would have been ignored or discarded. So that if black women were going to have behind them the power of the courts in seeking such jobs, white women were suddenly going to be the absolute last at the hiring gate in America and the first to be fired. But if the bill did not open jobs to black women, or gave them only the rights of white women, there were going to be some very surprised supporters of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.”

When writing the Act, “the Judiciary Committee had, I am sure, believed that they would give black men some rights and that black women would be treated about like white women. I am equally sure that it had never occurred to most of the black organizations supporting the bill that there was any discrimination at all against white women. And I am equally sure they expected black women to gain employment rights from the bill. Under any circumstances, I made up my mind that if such a bill was going to pass, it was going to carry a prohibition against discrimination on the basis of sex, and that both black and white women were going to take one modest step forward together.”

“We Are Human”

And so Martha Griffiths, after stopping the guffaws with her initial remarks, went on to show how the Civil Rights Act, for all its noble intentions, would not in fact protect black women, because they were still women. Noting a host of examples, she at one point asked that if the U.S. Constitution supposedly covered women, why was it necessary to pass the 19th amendment to give women the vote, when the 15th amendment said that all citizens could vote? “How could the language of the 15th amendment have given black men the right to vote, but not black women?” she wrote.

Griffiths, gaining steam, told her colleagues that day, “If you do not add ‘sex’ to this bill, you are going to have white men in one bracket, you are going to try to take colored men and colored women and give them equal employment rights, and down at the bottom of the list is going to be a white woman with no rights at all.” She said that their great-grandfathers had been willing “to be prisoners of their own prejudice” by permitting ex-slaves to vote, “but not their own white wives… . A vote against this amendment today by a white man is a vote against his wife, or his widow, or his daughter, or his sister.”

She asked three times to extend her time for speaking. “When my argument was complete, the House was abuzz.”

Others spoke for or against the measure, but as the Washington journalist Robinson wrote, when she had finished, “the outcome of the vote was never in doubt.”

The bill passed 168–133, with the remainder opting out of voting one way or another. “Up in the gallery, a woman’s shrill voice cried out, ‘We made it! We are human,’” Griffiths later wrote.

Shattering More Barriers

U.S. Rep. Martha Griffiths, ’40, shortly after the House added a sexual discrimination amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Pictured from left are Griffiths, journalist May Craig, House Rules Committee Chairman Howard W. Smith (D-Va.), and Katharine St. George (R-N.Y.). (Courtesy Library of Congress)

In what is her second most famous achievement in Congress, Griffiths and then-Congressman Gerald Ford worked together in 1970 to get enough votes to crowbar the Equal Rights Amendment out of committee, where it had languished since it was first introduced in 1923. “I could have kissed Jerry, I was so grateful to him,” Griffiths remarked in her autobiography. (The ERA was never approved by enough states, and is now back in committee.)

After Griffiths left the House, she kept shattering barriers. She was the first woman to serve on many corporate boards, and, in 1982, she became the first woman elected as Michigan’s lieutenant governor. After two terms, Gov. James Blanchard chose another running mate, leaving a sour note on that part of Griffiths’s long career.

She remained active for years after that until she died at age 91 in 2003—seven years after Hicks’s death. She did not live to see a woman elected president, but she did live to see Michigan’s first woman governor, Jennifer Granholm, who was elected in 2000.

“Not only did she break the glass ceiling in Michigan’s capitol,” Granholm told the Detroit Free Press when Martha Griffiths died, “but she modeled the way for all of us—men and women alike—to use the power of leadership to serve one another and improve our world for all of its citizens.”

Sheryl James has researched and written extensively about Martha Griffiths. James, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, is the author of Michigan Legends: Folktales and Lore from the Great Lakes State (University of Michigan Press, 2013).