For 16 years, Jodi Lopez, ’03, fought to save Matthew Reeves’s life—and twice his life was spared. But the hard-fought victories that Lopez, Ben Friedman, ’13, and others won on Reeves’s behalf were reversed by the US Supreme Court. In both cases, Reeves was not given the benefit of full merits briefing or a hearing. And the final decision—the one that green-lit Reeves’s execution—did not contain any explanation. For Lopez and Friedman, the case raises salient due process questions that warrant examination of and discussion about the American justice system.

Reeves’s conviction

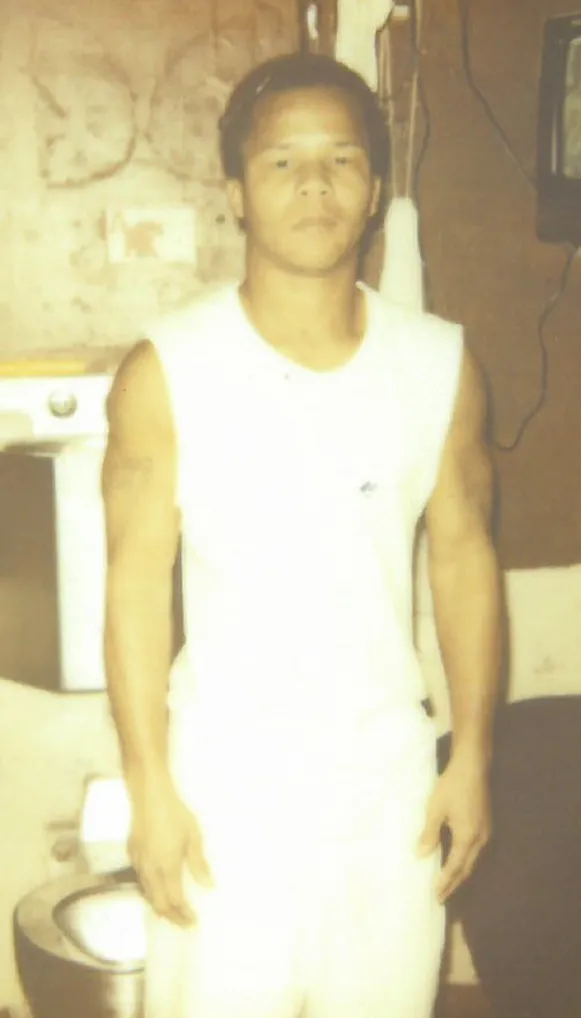

In 1996, Matthew Reeves was arrested for the murder of Willie Johnson. Reeves was 18 years old and didn’t have money to hire a lawyer. He was facing the death penalty.

There is no public defender system in Alabama’s state courts, so Reeves was represented by private lawyers, one of whom had never handled a death penalty case before. During their investigation, Reeves’s lawyers discovered evidence that Reeves may have had intellectual disabilities. Reeves failed the first, fourth, and fifth grades; was placed in special education classes; and consistently scored under 75 on IQ tests. And shortly before the murder, Reeves was shot in the head while sitting on his front porch. He survived but suffered a brain injury.

Based on this evidence, Reeves’s trial lawyers asked the court for $3,500 to retain a specific neuropsychologist to evaluate Reeves. Their goal was to develop mitigating evidence that would convince a jury to spare Reeves’s life. The government opposed the request, and initially the court agreed. But Reeves’s lawyers argued that a neuropsychology expert was the only way they could build a mitigation case and asked the court to reconsider. The court subsequently allocated the funds.

But Reeves’s lawyers never contacted their proposed neuropsychologist. The jury did not hear expert testimony about the extent of Reeves’s intellectual disability. After just 50 minutes of deliberations, and by a vote of 10-2, the jury recommended the death sentence.

A firm commitment

Lopez, a partner in the Los Angeles office of Sidley Austin LLP, first met Reeves in 2005, when she was a second year associate. She took on his case as part of Sidley Austin’s pro bono commitment to helping people on death row, who often lack even basic legal representation. From their first meeting, she was struck by his cognitive limitations.

“The huge impression that I had of Matthew was how childlike he was, and that was because of his intellectual disability. From the very beginning of the case, I truly thought in my heart he would never be executed,” she says. “He was not asking to be let out of prison, but he did not want to die.”

For Lopez, working to remove Reeves from death row is not to ignore the pain and suffering of the victim and family. He committed murder, and that act cannot be erased. But she says his mental disability and the abject poverty of his upbringing are important context, and that the case exemplifies the ethical gray areas of capital punishment.

“Someone emailed me once and said that Matthew should be executed, because even a 10 year old knows that murder is wrong. But to me that’s the whole point—you may put that 10 year old away in prison because they made that terrible choice, but we as a society don’t believe a 10 year old should be executed. So when I talk about him being childlike, that’s what I mean.”

Losses pile up in state court

Lopez spent her first two years on the case gathering information, talking to witnesses, and making document requests to different government agencies, hospitals, and mental facilities. Lopez and her colleagues eventually sought post-conviction relief for Reeves in Alabama’s state court.

In 2002, the US Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that executing someone with an intellectual disability violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The Atkins decision formed the basis for one of the two claims that Lopez and her colleagues would make in their years-long attempt to prevent Reeves from being executed. The other claim was ineffective assistance of counsel, based on the original trial counsel’s failure to contact the neuropsychologist and present evidence of Reeves’s intellectual disability to the jury.

Lopez’s research and investigation eventually led to an evidentiary hearing in 2006. Among other evidence presented, the hearing included testimony from the same neuropsychologist who the original trial counsel had said they would contact but never did. It was the first of many defeats in Alabama’s state and federal courts.

“We literally didn’t win for the first 15 years, but we were laying the groundwork,” she says. “It was always disappointing when we lost, because I always firmly believed in Matthew’s case, but it didn’t surprise me. I just focused on the long game.”

The strategy and patience paid off. In 2020, Reeves suffered another defeat in federal district court in Alabama. Around that same time, some of the senior associates who had worked on Reeves’s case were leaving the firm, and Lopez wanted to bring on new team members with appellate expertise for their appeal to the 11th Circuit.

“I did not think that I was the right person to argue at the 11th Circuit—I cared too much about Matthew, and I’m not an appellate lawyer,” she says. “I made some inquiries at the firm, and another Michigan graduate was identified to me as someone who was a stellar associate and was specializing in Supreme Court and appellate law.”

Ben Friedman, ’13, a senior managing associate in the Chicago office of Sidley Austin, had previously argued several successful claims of ineffective assistance of counsel in federal courts. Although they hadn’t met before, both Friedman and Lopez are double Wolverines, and he says their shared background gave them an instant rapport.

“When I heard about the circumstances of Matthew’s case, it’s a particularly egregious and heartbreaking set of facts,” he says. “His trial lawyers fought really hard to hire a specialist, they identified that person, won funds from the court, and then never called the guy. When you look at the case law around ineffective counsel, it’s rightfully deferential to how lawyers do their job, but the one thing you can’t do is not pick up the phone and not follow through on something as important as that.”

Lopez and her colleagues brought Friedman up to speed, and they got to work.

Habeas relief, temporarily

“By the time I signed on, we had about two weeks to put together a motion for reconsideration. It was a lot of late nights, making sure that we also got a notice of appeal on file and that Matthew was set up for all of the things that he needed going into the appellate stage,” Friedman says. “Once we had the district court’s decision, then we went through the appeal process. It was very much a whirlwind at that point. We had a lot to do.”

Friedman says that getting a federal court to overturn a state-court conviction is difficult, and the 11th Circuit has a reputation for strictly applying the law when it comes to federal habeas cases. But he and Lopez were cautiously optimistic going into the hearing, which was conducted over the phone due to the pandemic.

“Early on, there were one or two questions about Matthew’s ineffective assistance of counsel claim,” he says. “Once we started talking about that, it seemed clear that we had at least two judges who were going to rule in our favor on that claim. We felt good after oral argument, but you never know. We were still holding our breath.”

In November 2020, the panel ruled unanimously to grant Reeves federal habeas with respect to his sentence on the basis of the ineffective assistance of counsel claim.

“That was the first time that Matthew had won in his case, and the relief that we won for him was that he was supposed to get a new sentencing phase of his case,” Lopez says. “But that got taken away.”

A reversal at the high court

The State of Alabama appealed to the US Supreme Court, and in July 2021, the Supreme Court overturned the 11th Circuit ruling in an unsigned decision over three dissents. It held, among other things, that Reeves could not prevail on his ineffective assistance of counsel claim because his trial counsel did not testify at an evidentiary hearing, notwithstanding the other evidence that supported his claim. The Court did not allow a full merits briefing or hold oral argument.

In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote, “The lengths to which this Court goes to ensure that Reeves remains on death row are extraordinary….Today’s decision continues a troubling trend in which this Court strains to reverse summarily any grants of relief to those facing execution.”

Lopez then shifted her efforts to a clemency petition, which was submitted to Alabama Governor Kay Ivey. It was denied.

One last, lost appeal

After the Supreme Court reversed the 11th Circuit ruling, the Federal Defenders for the Middle District of Alabama brought a new lawsuit on Reeves’s behalf under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) challenging Reeves’s method of execution.

The Alabama state legislature had legalized lethal gas as an alternative to lethal injection in 2018, and the law gave all death row prisoners 30 days to choose the alternative method of execution. But the form to opt in was complicated, and Reeves, with the ability to read at only a third-grade level, did not understand the form and was unable to fill it out.

At the time of the case, Alabama had not yet developed protocols for death by lethal gas, and therefore death row inmates who had chosen lethal gas did not have execution dates. The suit argued that Reeves’s rights under the ADA had been violated because prison officials failed to provide him with the necessary accommodations to understand the form and the choice it presented.

In January 2022, a federal district court judge concluded that Reeves was likely to win on the merits of his ADA claim and enjoined the state from executing Reeves by lethal injection. Three weeks later, the injunction was unanimously upheld by a panel of judges on the 11th Circuit. The district and circuit courts prepared 64 pages of legal rationale in support of the injunction.

The following day, the Supreme Court vacated the injunction over three dissents. As with their previous decision, the Court did not allow for the merits of the case to be briefed or heard. This time, the majority did not explain their decision.

“It was just a feeling of utter shock and sadness. And not a single word of explanation,” Lopez says. “It just feels so wrong on a human level for someone with an IQ of 68. It haunts me.”

Two hours after the Supreme Court vacated the injunction, Matthew Reeves was executed by the State of Alabama. He was not given an opportunity to speak to his lawyers or anyone else. He had no last words.