The Law School’s Human Trafficking Clinic had been representing victims of labor and sex trafficking for more than a decade when its director, Bridgette Carr, ’02, began to envision a broader mandate for the clinic.

“I really wanted to think about how we could combat trafficking before people become clients,” Carr says. “How do we think about reducing vulnerability—like homelessness, mental health problems, or a criminal record—because that is what makes people likely to be trafficked.”

Around the same time, the clinic received a gift from an anonymous donor that would provide funds to help Carr realize her vision. In fall 2022, the clinic transformed into the Human Trafficking Clinic + Lab. While the clinic, which launched in 2009, continues to focus on direct representation and advocacy, the lab component uses multidisciplinary teams of students to develop solutions to reduce vulnerability to trafficking. Those solutions can occur at the policy, service, or industry level through partnerships with other organizations.

Despite their different goals, the clinic and the lab maintain a connection, says Courtney Petersen, ’21, clinical teaching fellow.

“In the lab, we’re being regularly informed by the lived experiences of the victim survivors that we’re helping in the clinic,” she says. “And so we’re able to keep a really close conversation between the community that we’re trying to serve and the grand-scale work the lab is doing.”

Courtney Petersen, ’21In the legal space, you’re often limited by a lot of external factors. But when you come into the lab, you’re not limited. All you’re asked to do is think of innovative solutions.

A complex problem that requires complex solutions

Human trafficking is the product of complicated social and economic forces, and Carr believed that the lab would be most effective with perspectives from multiple disciplines. As a result, the lab accepts applications from students in any graduate program at the University. To date, 62 law students have collaborated with 50 graduate students from 11 degree programs in the lab.

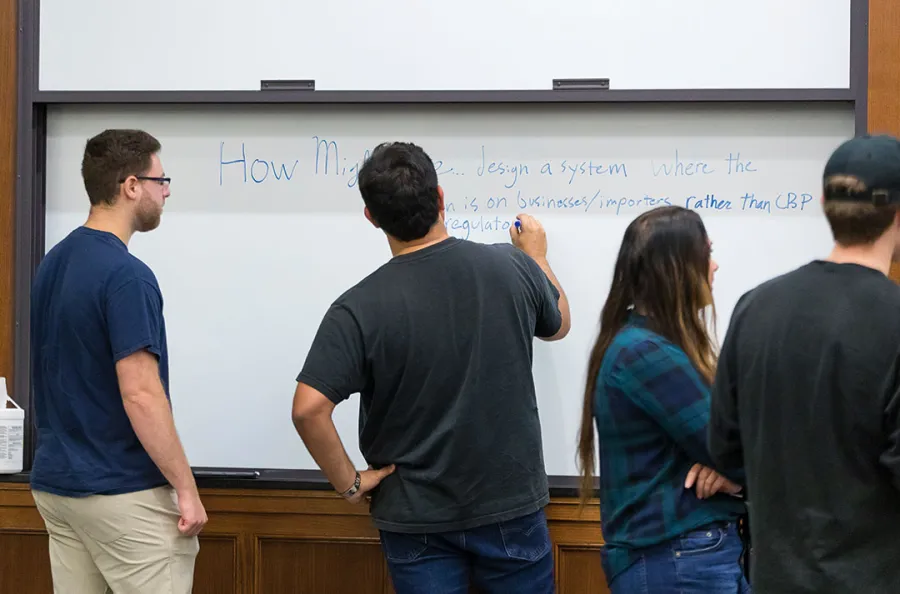

“In the legal space, you’re often limited by a lot of external factors. But when you come into the lab, you’re not limited,” says Petersen. “All you’re asked to do is think of innovative solutions.” That kind of thinking, she adds, means law students need to be comfortable being uncomfortable.

Josiah Himmelman, ’23, a student in the lab during its first semester, says the process was very different from his other law school experiences.

“In law school, I felt like I had a very neat checklist: ‘Here are the tasks. Do this, and you will succeed.’ But the lab was like charting your own course, so it was very unsettling for me at the beginning. I had to learn to be at peace with that uncertainty,” he says. “But human trafficking is a really complex problem, and it requires complex solutions.”

Carr drew upon similar multidisciplinary work she had done with the Law School’s Problem Solving Initiative (PSI), a rotating slate of classes that are open to students in other U-M programs and often co-taught with faculty and practitioners from different fields. But unlike the PSI, the work of the lab doesn’t end with the semester.

“One thing we try to do is veer away from the boundaries of the semester system,” says Petersen. “It’s not just pedagogical. The goal is implementation.”

Making expungements accessible

During its first semester, faculty in the lab presented students with the question of how to make expungements of criminal records more accessible. Past criminal convictions often serve as a barrier to opportunities in housing, employment, and education, which can, in turn, increase an individual’s vulnerability to trafficking.

While people can apply to have their criminal records expunged under current Michigan law, the process can be daunting for anyone unfamiliar with the law. And if they make a mistake, they need to wait three years before reapplying. Hiring a lawyer to help with the process is an option, but that cost—on top of the fees to file the paperwork—is out of reach for many.

Students in the lab developed a plan for a local employer to offer expungements of criminal records as an employee benefit and pitched the idea for a pilot program to Zingerman’s, an Ann Arbor culinary institution.

“We landed on Zingerman’s because they do a lot of good work and they are really interested in these types of endeavors,” says Himmelman. “We thought it would be mutually beneficial, because it would increase applications and promote more loyalty to the company.”

Zingerman’s agreed and began offering the benefit in spring 2023. It identifies employees who want the service, and students then work with them to have their criminal records expunged.

“We have had several employees take advantage of this benefit,” says Paul Swaney, human resources generalist at Zingerman’s. “It’s an anonymous tool, and there is no expectation that staff share when they have utilized this benefit. However, I did have a staff member approach me and tell me that she feels like an indescribable weight has been lifted from her shoulders.”

He adds: “We will do everything we can to help remove these barriers. We see it strategically as an important staff retention tool, but more importantly, we see it as the right thing to do.”

The expungement work continued into the winter 2023 semester. Another team of students developed a package of bills for the state legislature that would help make the expungement process more accessible. If passed, the legislation would limit penalties for mistakes on applications and remove the three-year waiting period. It also would allow for expungement assistance from nonlawyers, such as nonprofits that are already helping people apply for housing assistance and human resources staff at employers like Zingerman’s.

Rebecca Wong, who earned her master’s in social work from U-M in 2023, was part of that team. At the time, she had an internship with state Sen. Stephanie Chang through her social work program. The team met with Chang to propose the bill they developed, and the legislation is currently pending. Wong emphasizes that the multidisciplinary nature of the team made the bill package possible.

“I don’t think that what we did in the lab would have been possible without all of us,” she says. “My eyes were really opened to the nuanced ways that different disciplines think about a specific issue and the different skills that they bring.”

Having a positive impact

During the 2023–2024 academic year, the lab’s focus changed from expungements to combating forced labor in supply chains.

“We’re being approached now by outside stakeholders and partners related to forced labor,” says Petersen. “We did one major project that was focused completely on international forced labor in international supply chains. And we also had a major project that worked on domestic forced labor in US supply chains.”

Additionally, the Law School’s Business and Human Rights Lab was created recently to work with students in the Human Trafficking Clinic + Lab. Specifically, it will help businesses in understanding, preventing, and remediating any adverse human rights impacts of their operations. It also is developing systemic solutions to reduce vulnerability to trafficking and forced labor.

As the lab continues to work and grow within the Law School and University at large, Carr hopes law students will continue to explore multidisciplinary opportunities while they expand their vision of lawyering.

“I hope it helps them see the abundance of ways that their professional identity can have a positive impact,” she says. “I think students see how much they can contribute, how many different ways law and lawyers are affecting society. And I love that.”