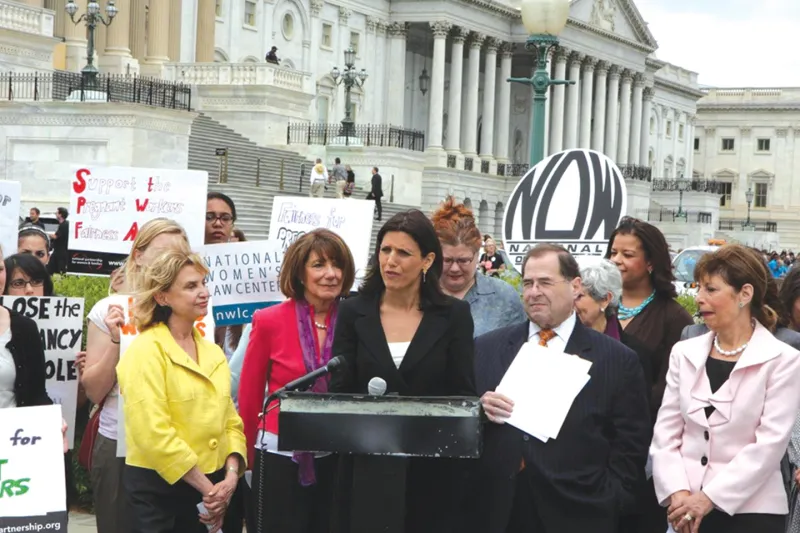

When the federal Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA) was reintroduced with bipartisan support in the U.S. Senate in June, it was a personal victory for Dina Leshetz Bakst, ’97. Bakst helped to draft the legislation, which provides stronger legal protections for pregnant women in the workplace.

“No woman should have to choose between a job and a healthy pregnancy,” says Bakst, co-founder and co-president of A Better Balance, a national legal advocacy organization that works to advance the rights of working families.

“An issue we see over and over again at A Better Balance is pregnancy discrimination, and we see how it plays out with low-wage workers who are often one new baby away from losing their jobs and landing in a poverty hole that will punish them for the rest of their lives.”

Bakst made the case for more equitable pregnancy-related workplace accommodations in her 2012 op-ed in The New York Times, “Pregnant, and Pushed Out of a Job,” which inspired members of Congress to introduce the PWFA that same year.

The law did not pass, but it garnered renewed support and bipartisan backing in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of Peggy Young in Young v. United Parcel Service. (Michigan Law Professor Sam Bagenstos represented Young in the case.)

The federal PWFA would require employers to reasonably accommodate workers with “known limitations” arising from pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions, unless to do so would impose an undue hardship on the employer. The law would ensure that pregnant workers would not be fired unnecessarily or denied reasonable job modifications that would keep them working while maintaining a healthy pregnancy.

“What the Supreme Court is requiring is that pregnant women jump through hoops to prove discrimination—a luxury of time and resources that many pregnant women don’t have,” says Bakst, who notes that existing pregnancy laws and discrimination laws are not enough to protect pregnant workers, because they place the burden on pregnant workers to prove intentional discrimination.

“Many times, a pregnant worker just needs to carry a water bottle, take extra bathroom breaks, or be temporarily relieved from light duty, and she needs that accommodation immediately, so that she’s not forced to make an impossible choice between honoring her doctor’s orders—stay off your feet or stay hydrated—and her paycheck. When there’s clarity in the law, which the PWFA provides, workers can use the law to proactively stay healthy and on the job.”

Bakst and her organization have helped 10 states and localities—including New York City, where A Better Balance is located—pass legislation aimed at protecting pregnant workers and new mothers from discrimination in the workplace.

The law in New York City is “one of the best,” Bakst notes, and includes not only accommodations during pregnancy but also protection for women recovering from childbirth and requires that a reasonable time and place be made available for nursing mothers to pump breast milk.

Bakst’s legislative efforts also address paid sick leave, paid family leave, and fair and flexible work schedules for all caregivers. Last year, she and A Better Balance were instrumental in helping pass New York City’s Earned Sick Time Act, which allows covered workers to take up to 40 hours of sick time in a year, either for themselves or to care for family members, without being fired or punished.

“We don’t just help to pass the laws,” Bakst says, “we help to enforce them,” adding that she and her colleagues serve as advocates for workers when employers aren’t following the law. Bakst represents clients seeking legal help through her organization’s Families at Work Legal Clinic and its associated hotline, and helped to develop Babygate, an online resource for workers that helps them understand pregnancy and parenting laws in a state-by-state guide.

Bakst, who cofounded A Better Balance in 2005, says she is encouraged by the progress that has been made with fair and family-friendly workplace policies during the past decade, but she points out that more work needs to be done to achieve equality in the workplace.

“It has been incredible to be part of this growing national movement, where people are seeing issues related to work and family as systemic issues that affect all of us, but have particularly devastating consequences for lower-income workers. There is a growing recognition of the need to do something about it, and that is encouraging.”