You couldn’t get a divorce this quickly in Vegas.

But it wasn’t the more than 300 couples, married in Michigan this spring, who wanted their marriages to end. It was the State of Michigan.

The couples married on March 22, 2014, the day after U.S. District Court Judge Bernard Friedman overturned Michigan’s ban on same-sex marriages. But by late that afternoon, after all 300 couples had been legally married, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a stay of Friedman’s ruling—a stay that didn’t address the legal status of the marriages that had already been solemnized.

A few days later, the governor’s office said in a prepared statement that, while the marriages were legal, the appellate ruling meant “the rights tied to these marriages are suspended until the stay is lifted or Judge Friedman’s decision is upheld.”

In the view of the American Civil Liberties Union, the governor’s statement contradicted itself. How could the marriages be legal, yet the rights and responsibilities attendant on them be denied, even temporarily?

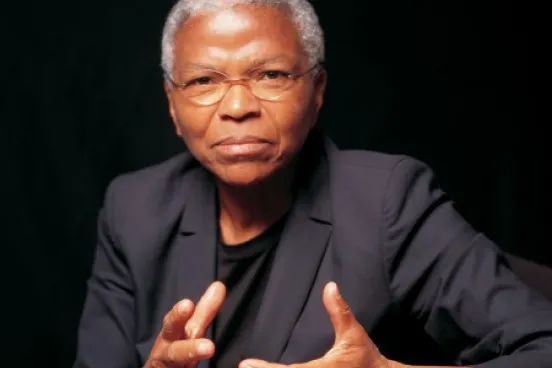

The group approached Michigan Law Professor Julian Davis Mortenson, a longtime litigator for LGBT rights, and he quickly agreed to spearhead a lawsuit. Less than three weeks later, that suit was filed on behalf of eight couples affected by the state’s reversal.

“First and foremost, it’s important that these clients—these particular human beings, who have relationships that span decades—not be subjected to a mandatory divorce by the state,” Mortenson says. “The 16 people in our lawsuit have lost something precious and dear to them, and that’s outrageous.”

Beyond that loss, of course, lay a thicket of problems created when the couples’ marriages were suddenly hurled into legal limbo.

For plaintiffs Clint McCormack and Bryan Reamer, who have been together more than 22 years and have 10 adopted and three foster children, those problems include being unable to include both parents’ names on some of their children’s birth certificates.

“Some of our children we adopted together, in another state, and some we were unable to adopt together” because Michigan requires couples to produce a marriage certificate, McCormack says. “People think it’s just a piece of paper, but that piece of paper has so much weight to it when you’re raising children.”

McCormack says their family has been spared some of the problems plaguing the other seven families involved in the suit—insurance and pension issues, for example, or the denial of state-level benefits for the partner of a Michigan National Guard member—but that’s not to make light of what the state is currently denying him, his spouse, and his children.

“I just wish these people who make the laws could get with reality and realize they’re harming the children,” McCormack says. “To me, it’s legalized child abuse, plain and simple.”

Mortenson argued for a preliminary injunction Aug. 21 before U.S. District Judge Mark Goldsmith, maintaining that his clients are legally married, regardless of what happens at the Sixth Circuit or at some future time in the U.S. Supreme Court. The case isn’t about getting married, he argued—it’s about staying married. The state, meanwhile, argued against the injunction and urged Goldsmith to wait and see what the appeals court decides. For now, Mortenson says, that’s where the case stands.

“These people have been living under a cloud of legal uncertainty for months,” he says. “These are real people, facing real pain, real sorrow, and real-life challenges caused by the state’s refusal to recognize their marriages.”

At the same time, he adds, it’s obvious to anyone who is paying attention that views on marriage equality are evolving—just not rapidly enough for 600 people who felt joy at being married, then bewilderment and disbelief when they were told those marriages were legal but weren’t going to be recognized by the state.

“If this case comes out the right way, it will offer these 600 people a security and a respect that will make a big difference to them,” Mortenson says. “Having same-sex couples living their lives together in Michigan with the full imprimatur of the state, as something perfectly normal and ordinary and something to be celebrated, is going to reverberate broadly.”