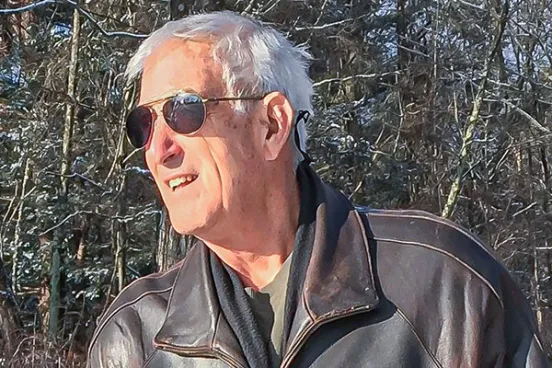

With her election as a justice on Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court in 2011, Susanne Baer, LLM ’93, made history. She became only the second nominee of the country’s Green Party and the first out and elected, rather than appointed, lesbian and radical feminist to serve as one of the court’s 16 justices.

“I was an exception to the mainstream rule, and that's what the Green Party was looking for,” says Baer. However, with her background, she knew at the time that the nomination “included the assumption that it would not be easy.”

Easy or not, she gained the necessary two-thirds majority in the federal houses of the German parliament, including support from the opposition parties. Baer, who recently left the court at the conclusion of her 12-year term, says that her election was a surprise to many people, considering her background of speaking out on feminist causes and her work as a critical scholar.

However, a deeper look at her background—including as a professor of public law and gender studies at Humboldt University of Berlin and a William C. Cook Global Law Professor at Michigan—reveals a clear commitment to the country’s constitution. In some way, all her work emphasizes the idea of “never again” that informs German constitutionalism, meaning that the atrocities of the Holocaust will not be repeated.

“My country rings a historically very charged bell,” she says. ”We cannot leave nationalism and national pride to right-wing radicals, neo-fascist movements, populist movements who try to capture national feelings and national identity.”

Germans of her generation have struggled, she says, with what it means to be German and how much of a national identity can be configured as a positive element in today's world. Yet she came to terms with it and with her role as a judge.

“So I think it's the highest honor to serve on the court and contribute to ‘never again.’ My commitment to the national constitution is the commitment that human rights violations and an abuse of democracy will never happen again. And if that is activism, then every judge has to be an activist.”

Susanne Baer, LLM ’93“If you are in such a high position, with so much responsibility, and people put you there because they trust you, I think part of what you have to give is your authenticity and your honest take on life.”

Consequential cases

Baer’s educational background and academic career have served her well on Germany’s highest constitutional court. She earned her law degree at the Free University of Berlin and her LLM at Michigan Law, wrote her dissertation at Goethe University Frankfurt, and wrote her habilitation as a postdoctoral researcher at Humboldt University before joining the faculty there.

The tasks of German law professors go beyond teaching and research. They also serve as advisers to government officials and appear in court and testify in parliament—which meant for Baer that she was well versed in the ways of government and politics when she began her term.

“Professors are experts in all fundamental questions of the state and politics,” Baer says. “And based on what I saw, I have a deep respect for politicians and legislative politics. My sense of a separation of powers is as developed as my sense of the commitment to human rights and democracy. So this makes me a judge who would do everything to defend human rights and democracy, yet not strangle the political process.”

While Baer worked on several thousand decisions during her tenure, a few stand out as particularly notable.

One of the decisions came in early 2020—Neubauer, et al. v. Germany. In that case, nongovernmental organizations, citizens from the global South, and young Germans who challenged the government over its climate protection act argued that its targets for lowering greenhouse gas emissions were insufficient. Baer says that the case was particularly tricky because of the “knowledge crisis,” meaning that some do not believe there is a climate crisis, which required the court to assess the facts more meticulously than usual. In addition, there was doctrinal innovation.

“The decision was that the climate protection act was a violation of their liberty rights,” says Baer. “That was a surprise to many. It's also a decision of international dimensions.”

Another important case, which was brought by nine people with disabilities, involved the distribution of medical services in the event of resource shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. The court ruled in the Triage Decision that the legislature had violated the constitution’s discrimination protections and had failed to ensure that people with disabilities were not at risk of being disadvantaged in the allocation of life-sustaining treatment when supply was constrained.

“We talked to a lot of medical experts to get their opinion and advice and expertise,” says Baer. “Then we were the ones to assess: What are the facts? What is the risk? What is life threatening? What can be done? And I think those questions in life-and-death situations are particularly challenging. It was a very, very tricky factual and bioethical, but also legal, decision.”

Baer served as the reporting justice on the case, adding an extra layer of challenge.

“You are responsible to get all the information there is, everything out there, including comparative material and scholarly work, to prepare your colleagues to make a wise decision.”

A third notable case decided during her tenure on the court allowed gay people to adopt a child who had been previously adopted by their partner. She was not the reporting justice but, like all of the judges in senate rulings, was intensely involved.

“We decided the adoption case in my early years on the court. I was nervous going into deliberations with seven colleagues I didn’t yet know well,” says Baer. (The 16 justices of the court are divided into two senates of eight justices each.)

“I didn't know what kind of prejudice they might have, and I didn't know what they thought about gay parents adopting children and whether they would assume a position I did not have, beyond a stereotype. And it was totally unclear whether we would be able to put the prejudice, the assumptions, the fear, the concerns, the ambivalence on the table and talk about it.”

However, she and her colleagues, whom she terms “brilliant,” had an honest and fair discussion about the issues of gay parents adopting children. In the end, they decided 8-0 to give gay parents equal rights to a successive adoption.

That case, of course, touched her on a personal level as the first openly gay member in the court’s history. And despite her work against reducing people to one identity, the issue of when and how sexual orientation matters remained significant in many ways.

“If you are in such a high position, with so much responsibility, and people put you there because they trust you, I think part of what you have to give is your authenticity and your honest take on life.”

Return to the classroom

Baer’s interest in feminist legal studies was just one of the reasons she chose Michigan Law from the many law schools that accepted her application.

“I came to Michigan because I wanted to study in the United States, being interested in critical perspectives on the law that were not as present in European or German scholarship at the time.”

She particularly looked forward to studying with feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, the Elizabeth A. Long Professor of Law, and they continued to collaborate well after Baer earned her LLM. She also was drawn to Michigan’s mix of students from all backgrounds.

“I fell in love with the ‘down to earthness’ of Ann Arbor. It’s a great school with a fantastic reputation, but people are not totally full of themselves just because they are there.”

Although she paused her academic career when she joined the court, justices keep their professorships at a German university and return to their jobs after their judicial service. At Humboldt University, she now serves on both the law and philosophy faculties, where she is able to apply the lessons she learned as a justice with teaching and research in public law, legal theory, and sociolegal as well as intersectional gender studies.

“Teaching and working with younger minds, that is a total gift to me,” she says. “And it's still feminist legal theory, and it's still comparative constitutionalism. But I hope, at least, that it's now enriched by what I've learned as a justice.”