Usama “Sam” Hamama emigrated from Iraq to the United States when he was 11 years old. At age 56, he has never returned. Yet despite having spent decades living, working, and raising a family in West Bloomfield, Michigan, he was one of more than 300 Iraqi nationals, about half of whom are from Metro Detroit, identified in 2017 by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for removal. Having overstayed their visas or lost their immigration status because of criminal convictions, these individuals were rounded up by ICE agents and headed for mass deportations.

Hamama and many of the other detainees were scheduled to be returned to Iraq in June 2017. Had that happened, they would have been likely to face persecution, torture, or even death upon their arrival. The Detroit-area detainees were mostly Chaldean Christians whose community in Iraq has dwindled under devastating persecution.

However, thanks to the efforts of a team of lawyers and students—including Professor Margo Schlanger; her Michigan Law student assistants; and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Michigan—the Iraqi detainees were spared that fate.

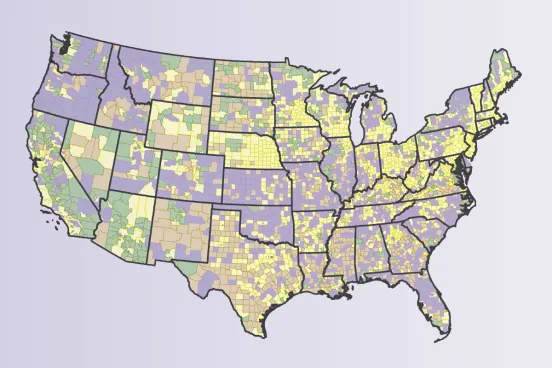

ICE’s mass arrests of Iraqis followed President Donald Trump’s executive order barring admission into the United States of nationals from seven countries, including Iraq. In March 2017, Iraq was dropped from the list when it agreed to accept U.S. repatriations, most of which it had rejected for decades. A small repatriation flight occurred in early April, and ICE also prepared for a much larger effort covering hundreds of Iraqi nationals nationwide.

In Detroit, a roundup of more than 100 individuals took place on June 11–12, 2017. A fledgling legal services organization, CODE Legal Aid, scrambled to find immigration lawyers for those affected, but it was clear that a group response was needed as well. On June 13, the Chaldean Community Foundation held a gathering at its headquarters in Sterling Heights, Michigan. It was then that Michael Steinberg, legal director of the ACLU of Michigan and public interest/public service faculty fellow at Michigan Law, was first approached about leading the legal movement to free the detainees. “I knew it wasn’t going to be easy, and that I would need to tap an unprecedented amount of resources,” Steinberg says. His first call? Schlanger, the Wade H. and Dores M. McCree Collegiate Professor of Law. “As co-counsel, she and Miriam Aukerman of the ACLU of Michigan have devoted their lives to this case,” says Steinberg.

With the support of the national ACLU; Miller, Canfield, Paddock, and Stone PLC; Michigan Immigrant Rights Center; CODE Legal Aid; and the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP), Schlanger and the ACLU of Michigan filed a class-action lawsuit,Hamama v. Adducci, on June 15, 2017, seeking a stay of removal. The lawsuit was named after lead plaintiff Sam Hamama.

“If we are going to have a system where we deport people—which is a severe outcome—we have to make sure that the system is fair,” says Schlanger, former head of civil rights for the Department of Homeland Security during the Obama administration and a leading authority on civil rights issues and civil and criminal detention. “It’s procedurally unfair to deport people without giving them an adequate chance to explain why they should not be deported. It’s even worse to coerce them into deportation by putting them in jail until they agree. And it’s substantively wrong to deport people into harm’s way. The government has done all three of these things in this case, and it’s outrageous.”

Halting Hamama’s plane to Iraq while the court assessed the lawsuit, The Hon. Mark A. Goldsmith of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan approved an emergency order on June 22, 2017, for Michigan detainees, and expanded it nationwide on June 26. A month later, Judge Goldsmith granted a preliminary injunction that prevented deportation while detainees sought relief through immigration court. It was a huge victory for the detainees, but the government appealed.

While that request was under consideration, and while the individual detainees reopened and fought their immigration cases, ICE continued to arrest more. It was their detention that became the focus of their next phase of litigation, says Schlanger.

In November 2017, the plaintiffs’ team filed a petition for the release of detainees under two theories. First, they said, it violated both the underlying detention statutes and the Constitution’s Due Process Clause to hold individuals seeking immigration relief for a prolonged period unless those individuals were shown to pose a threat to public safety or a flight risk. Each of them, the new motion argued, were entitled to a bond hearing, where an immigration judge could assess those threats and release them if appropriate. Second, they sought release underZadvydas v. Davis—a 2001 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that blocked indefinite detention of immigrants—arguing that in the months since the case had started, it had become clear that Iraq was not agreeing to these involuntary repatriations.

The result was a partial victory for the detainees. On January 2, 2018, Judge Goldsmith agreed that prolonged detention could not be continued without bond hearings and their individualized determination that detention served a legitimate purpose—public safety or avoiding flight by a particular detainee. He granted a second preliminary injunction, resulting in hundreds of bond hearings that mostly led to releases. The government appealed this order, too.

Judge Goldsmith later ruled in January that the court had not yet been given enough information to assess the broader claim underZadvydas v. Davis, and he ordered expedited discovery. After a first round of discovery, the ACLU (with Schlanger) filed its third major motion: It sought release underZadvydas in addition to sanctions against ICE for misrepresentations to the court and repeated delays in providing documents to the court.

Discovery revealed that at the same time ICE told the court that Iraq was fully cooperating with repatriations, Iraq was denying permission for repatriation flights and largely holding to its longstanding policy against forcible returns of its nationals from the United States. “What they claimed in June, July, and December 2017—that Iraq had agreed to take back its nationals—was false,” says Schlanger. “Our discovery demonstrated that Iraq was not at all likely to agree to the mass deportations the administration wanted.” In fact, it turned out that Iraq had rejected a repatriation flight in June 2017 around the time Hamama had been scheduled to return. In addition, as theHamama team sought more details, the government failed to meet a number of deadlines for document and information disclosure.

On November 20, 2018, Schlanger and the ACLU of Michigan received their third major victory: Judge Goldsmith entered a third preliminary injunction, requiring roughly 100 remaining Iraqi detainees to be released in time for the holidays.

In the meantime, the government’s appeals of the first two preliminary injunctions from June 2017 and January 2018 were decided. The judgment, announced publicly on December 20, 2018, was the first negative ruling for Schlanger and the ACLU of Michigan. The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the district court had lacked authority to grant the stay of removal, and that the decision related to bond hearings could not permissibly provide class-wide rather than individual relief. “With so many steps forward, we were bound to take one back,” says Schlanger. Steinberg agrees, adding that while most of their clients have received the relief they sought, this decision, if not reversed, will set a bad precedent, “particularly regarding the jurisdiction of the U.S. District Court to adjudicate a class action like this,” he says. “This will have significant consequences going forward, but there are appeals available to us through either the Sixth Circuit Court or the U.S. Supreme Court, sittingen banc. The case is not over yet.”

These last two years, there have been two main sources pushingHamama v. Adducci forward: the Iraqi immigrant community and the legal professionals seeking justice on their behalf. “I’m truly grateful not only to the families who stood up for their rights but also to the attorneys—people like Margo Schlanger, who spent her entire sabbatical working on this case,” says Steinberg. “Without her, without the firms and the hundreds of individual attorneys, paralegals, interns, and students volunteering their time pro bono, people would have died.” As Steinberg indicated, Schlanger wasn’t the only attorney with Michigan Law connections who devoted significant pro bono hours toHamama. Miller Canfield attorneys involved with the case include alumni Michael McGee, ’82, CEO; Larry Saylor, ’76, senior counsel; Brian Schwartz, ’05, principal; and associates Joel Bryant, ’14; Russell Bucher, ’17; Erika Giroux, ’17; Jacob Hogg, ’16; Thomas Soehl, ’11; and James Woolard, ’13. Immigration law expert Russell Abrutyn, ’99, and 3Ls Anna Yaldo and Allison Horwitz also assisted the team.

During their 1L summer and before a stay of removal had even been issued, Yaldo and Horwitz helped the hundreds of pro bono attorneys contesting the individual immigration cases of class-action members throughout the nation assemble their individual filings. Together, they created a website, hosted by IRAP, to support those lawyers. The site contains a variety of resources from sample pleadings to webinars on how an immigration case works.

“I have so much pride in what I have done and what I am doing. I’m grateful to be a part of this,” says Yaldo. “I’m not an attorney yet, but I’m still able to give back to my community.” The daughter of two Iraqi immigrants and a member of the Chaldean community of Metro Detroit, Yaldo feels a personal connection to the case and became deeply involved in the effort. She speaks Aramaic, the Iraqi Chaldean language, and was therefore able to serve as an interpreter for the ACLU’s meetings with class-action members in detention centers and jails in Youngstown, Ohio, and Port Huron, Michigan. Yaldo’s engagement even inspired her mother to join the cause; she occasionally accompanied her daughter as a second translator. “A lot of the men that I meet are my dad’s age and came to the United States about the same time that he did,” says Yaldo. “For me, that really hits home.”

Yaldo also tracks the individual immigration case appeals of each class-action member, and created a master notification list to ensure that the entire litigation team remains abreast of proceedings across the country. In addition, she has assisted CODE Legal Aid in organizing family events to deliver updates about the lawsuit. “One of the problematic things that happens with a case like this is that class-action members and their families will consume misinformation from a variety of sources,” says Yaldo. “It can cause panic, and we wanted to get ahead of that by making sure everyone was on the same page.”

Yaldo’s experience withHamama v. Adducci has spanned nearly her entire career at Michigan Law and opened her eyes to the workings of the immigration and criminal justice systems, reaffirming her commitment to becoming a public defender. “Every day in class, I read and hear about cases that are decades or even hundreds of years old, but I don’t actually get to see how they become what they are,” says Yaldo. “In this case, I got to experience it from its infancy. I am getting to see how it progresses, including the loss in the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. As devastating as that was, I got to witness how the appeals process works and what things look like in real time, when they are impacting the lives of people around me.”

Steinberg notes that the case continues; the government has appealed the third preliminary injunction, but it remains operative. Class-action members—including Sam Hamama, who was released last December—are nearly all out of detention, seeking immigration relief from their homes rather than from behind bars. In fact, on January 15, 2019, Judge Goldsmith ordered ICE to allow back into the United States one class-action member who had been deported to Iraq last summer in violation of the court’s June 2017 order. He returned on January 29.