When the owners of Detroit Soul decided to expand their catering and carryout business on East 8 Mile Road and open a full-service restaurant at a different location, they set out to create a neighborhood-friendly space that would both feed and support the local community.

The new restaurant would do more than simply expand access to their particular brand of healthier, locally sourced soul food. The proprietors, Jerome Brown and Samuel Van Buren, were committed to providing quality jobs for nearby residents.

Even for experienced small-business owners like Brown and Van Buren, launching a new venture can be a complicated affair and requires leveraging every available and affordable resource. Enter the Law School’s Community Enterprise Clinic (CEC), which provided free legal services to the entrepreneurs’ business as they worked through the details of the new location.

In December 2022, Brown and Van Buren launched Detroit Soul’s newest outpost on East Jefferson Avenue and began serving catfish fritters, chicken and pork chops, black-eyed peas, and other classic soul food dishes to hungry patrons.

For students in the CEC, Detroit Soul is one client among many, as they work under faculty supervision to help revitalize and reinvigorate urban communities across Michigan.

Collaborator with local businesses

The CEC promotes community and economic development in disinvested Michigan cities by supporting organizations that have a mission beyond the bottom line. The clinic, founded in 1991, has clients in Flint, Saginaw, Ypsilanti, and elsewhere, with an emphasis on Detroit.

“Detroit has been particularly adversely impacted by governmental policies and individual practices that have disinvested and segregated many urban communities,” says Dana Thompson, ’99, clinical professor of law and director of the CEC. “These governmental policies and individual practices have disproportionately affected communities of color. And there aren’t enough financial and other resources for these communities to address the myriad issues impacting them.”

One of the ways that the CEC currently finds new clients is by partnering with the Detroit Neighborhood Entrepreneurs Project (DNEP), which is housed in U-M’s Ross School of Business. The CEC began working with DNEP in 2016. DNEP recruits clients and points them to the CEC as well as six other U-M schools and colleges that provide services like marketing and design.

Christie Baer, DNEP’s managing director, says that “law is one of those things that people shouldn’t be trying to figure out on their own. But when you look around at the services that are available to business owners in Detroit, there is a massive gap in affordable or pro bono legal services for business owners. So the CEC fills this gap.”

Initially, the CEC worked primarily with nonprofit affordable housing developers but expanded in the 2000s to work with other neighborhood-based small businesses, social enterprises, nonprofits, community-based organizations, and cooperatives. This opened the door for the CEC to collaborate with a wide variety of organizations—from restaurants, birthing centers, and hair salons to urban farms, worker cooperatives, and community land trusts. The clinic has represented more than 500 clients since its founding.

Law students work with clients on a variety of transactions that not only help launch the business or nonprofit but also maintain its success, such as determining what type of entity to form; how to structure their governance; drafting and reviewing leases and contracts; and advising on trademark, copyright, and employment law matters. Without the clinic providing technical expertise, many clients would put their organizations at legal risk or have to pay full price for legal work.

“If it wasn’t for the clinic, we probably wouldn’t be as far along on our trademarks and other information, and we wouldn’t be as knowledgeable as we are now about these issues,” says client Deirdre Roberson, who co-founded The Lab Drawer in 2018. The Lab Drawer provides science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) educational kits for K–12 students.

Co-founder Alecia Gabriel agrees that the clinic students have made the legal aspects of their business easier to address.

“I think with the level of detail that the students have gone into for us, we wouldn’t have been able to do it as effectively and as efficiently,” she says.

And while businesses and nonprofits benefit from the students, students also derive lessons from their clients.

“A lawyer’s job is to know the law,” says Thompson. “But interpersonal skills are key to working with the clients successfully. I think our students begin to learn that developing these interpersonal skills, which are soft skills, is just as essential as developing their legal knowledge. They are vital to a successful attorney-client relationship.”

A positive impact on communities

While the transactional work the students do is essential, social justice plays a key role in the mission of the clinic. Thompson says it’s important for the clinic’s students to understand that business law can have a distinct, positive impact on communities.

So at the start of each semester, students in the CEC take a tour of Detroit, where they meet some of the clinic’s past and current clients. They also learn about the city’s history and the policies that have contributed to its current socioeconomic conditions, which provides important context for the social justice component of the work they will do. (See the photo gallery below for more about the tour.)

“The type of work we’re doing has been historically inaccessible to a lot of people,” says Sandy Sulzer, ’23, who took the clinic during the winter 2023 term. “But if you’re looking at a city that is revitalizing itself, it's essential for local entrepreneurs and local social engineers to have access to those tools.”

She adds that the clinic not only helps clients solve discrete issues, it also connects them to other resources in the community and other professionals engaging in similar work. That, in turn, can help an entire neighborhood.

“A neighborhood is only as strong as its businesses,” says Baer, the DNEP managing director who helps connect the clinic to new clients. “A restaurant might not be a particularly complex business model and the legal issues might not be novel, but they still have to be addressed. The community element is vital as the clinic helps build communities one business at a time.”

The social justice aspect extends to the people who are hired as employees.

“We were intentional about who we employ,” says Roberson, of The Lab Drawer. “So not only do we employ our staff throughout the year from the city of Detroit, but all our interns.” Two interns who attended Detroit Public Schools are now in their freshman years at Yale and Spelman College, both in STEAM fields.

3L Jacinta Onu knows from firsthand experience how resources like those the CEC provides can affect a community.

“My uncle runs a small business in Philadelphia,” she says. “So I have a personal connection with some of the difficulties in getting your business up and running and having access to information—people who can answer your questions, who can help you through some of the bureaucracy that takes a lot of time.”

She worked during her 2L year with urban farms in Detroit who wanted to address the food deserts in their communities.

“They all wanted to do something for their neighborhoods; they weren’t profit-making endeavors,” she says. “They were coming up with very creative ideas to tackle problems. To be able to have been part of that, to make one bit of the process a little bit easier, was inspiring.”

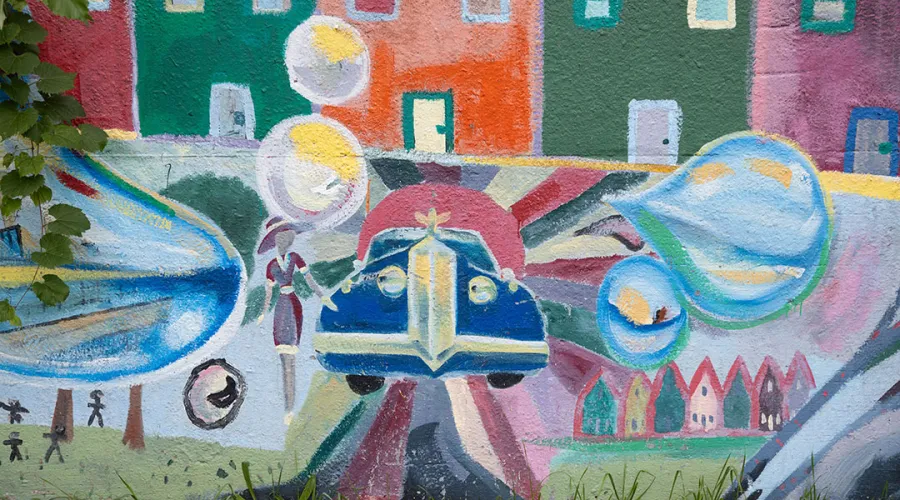

Students in the Community Enterprise Clinic start the term with a tour of Detroit, where they meet with clients and learn about the city's history. In September, they visited the Birwood Wall, which was built in 1941 to segregate the city.

Students in the Community Enterprise Clinic start the term with a tour of Detroit, where they meet with clients and learn about the city's history. In September, they visited the Birwood Wall, which was built in 1941 to segregate the city.

Feodies Shipp III, associate director of U-M’s Detroit Center, tells students the story of the Birwood Wall.

Feodies Shipp III, associate director of U-M’s Detroit Center, tells students the story of the Birwood Wall.

Students started the tour at the Birwood Wall, which received a historical marker in October 2022.

Students started the tour at the Birwood Wall, which received a historical marker in October 2022.

The tour included visits to businesses and organizations that have worked with the clinic, including the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network. The organization, the clinic’s longest-standing client, is developing the Detroit Food Commons.

The tour included visits to businesses and organizations that have worked with the clinic, including the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network. The organization, the clinic’s longest-standing client, is developing the Detroit Food Commons.

Students learned more about the Detroit Food Commons from Malik Yakini, executive director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network.

Students learned more about the Detroit Food Commons from Malik Yakini, executive director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network.

Susan Chase stands at the table as she and the students await lunch at Baobab Fare, another clinic client. Chase, visiting clinical assistant professor of law in the clinic, led this year’s tour.

Susan Chase stands at the table as she and the students await lunch at Baobab Fare, another clinic client. Chase, visiting clinical assistant professor of law in the clinic, led this year’s tour.

Following the client’s lead

Students take a client-centered approach in their work, Thompson says, which means understanding the clients’ values and purposes and using that information to guide their approach.

“Clients made decisions about how to proceed,” says Sulzer. “We did not say, for example, ‘Your organizational structure should really be a 501(c)(3).’ We asked about their goals and then facilitated a legal strategy with that ongoing conversation. They feel very empowered about why legal choices were made because they decided what was best for them.”

Onu hopes to carry that client-centered approach forward into her legal career.

“I know that there is a space to push boundaries and to basically think outside the box,” she says. “And I think it’s also good for lawyers, because we don’t have all of the answers. I need to remember that the communities I want to work with—my future clients, people that I want to help—are better suited to create their own solutions.”

Back at Detroit Soul, as the lunchtime crowd wanes and Jerome Brown looks again at his pages-long to-do list, he reflects on the work he’s done with the CEC to expand his restaurant business. He also realizes that expanding his business has provided a great learning experience for the CEC students.

“It was so involved, what we were doing,” he says. “And when the semester ended, another group of students came in and had to catch up. But I like that because it gave another set of eyes on what we had previously done. And it helps another group of students to learn as well.

“And we got a chance to feed them some great soul food—that was the best part.”