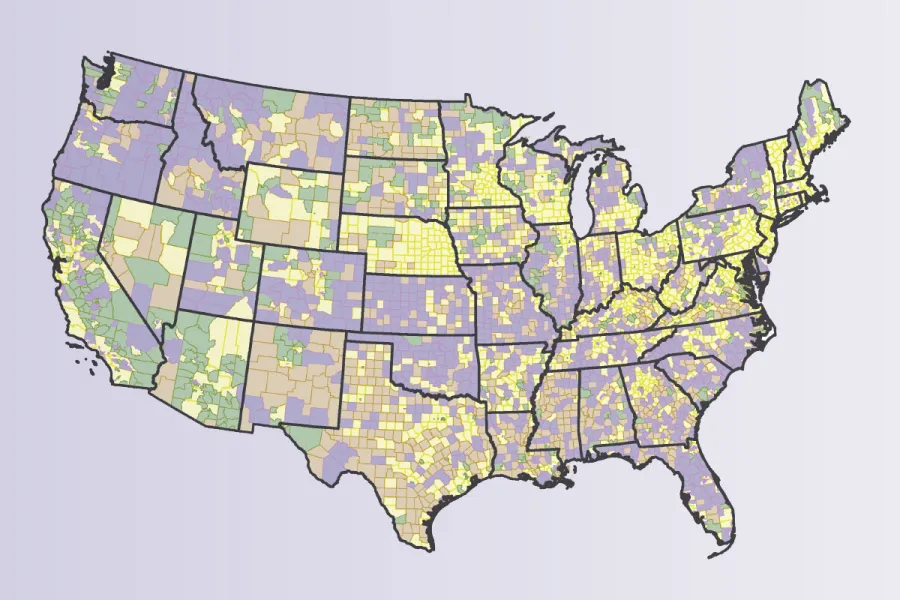

Lawyers are trying to help foreign-national physicians who are trained in the United States stay in the country to treat medically underserved patients. The process is reportedly laborious and burdensome to employers and physicians alike. We look at this lesser-known facet of federal immigration law, one that is potentially vital to the nation’s healthcare needs.

Most foreign nationals who complete their medical residency or fellowship in the United States must return to their native country for at least two years afterward, but they can apply for a waiver that will allow them to stay and work in a geographic or specialty area that is underserved. That process is long, complex, and costly—so much so that one of Kristen Harris’s clients dreamed of practicing in the United States but ultimately said, in essence, Forget it; I’m going to Canada.

Harris, ’98, specializes in immigration cases, including many that involve foreign nationals who are physicians. She works with healthcare facilities and doctors to request waivers of the requirement that the doctors return to their home country for two years under the terms of their J-1 visas, which are used by people who participate in work- and study-based exchange programs. She has been very successful in doing so, but she understands her client’s frustrations.

“The immigration system can be outmoded and dysfunctional when it comes to hiring the best and brightest,” says Harris, founder of the boutique firm Harris Immigration Law in Chicago. “We have huge swaths of medically underserved areas, yet even a straightforward J waiver case can run for nine to 10 months.

“The real issue is that we’re heading toward a health care crisis in this country,” adds Harris, also the advocacy co-chair of the International Medical Graduate Taskforce. “We have the means at our disposal to have a U.S.-trained workforce…if we could fix the system.”

Harris is optimistic about the prospects to fix the system, given recent executive-branch announcements regarding immigration. “The administration has signaled it recognizes the potential value of physician immigration. What we have right now is a unique window of opportunity. Minor administrative fixes could provide major policy benefits—improved health care access for Americans and lessened the burden on safety-net facilities seeking to hire qualified, U.S.-trained foreign national physicians.”

J-1 medical doctors can apply for a waiver of the two-year residence requirement under the Conrad 30 Waiver program. Each state has developed its own application rules and guidelines, but in all states, the following must occur for the application to be approved: The doctor must agree to be employed full-time in H-1B nonimmigrant visa status at a health care facility located in an area designated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as experiencing shortages, a Veterans Affairs facility, or a facility that provides care to residents of medically underserved areas; must obtain a contract from such a facility for a three-year term; and must obtain a “no objection” letter from his or her home country if the home government funded the exchange program.

Each state, as well as the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico, can recommend up to 30 waivers a year. The challenge arises in working with the different rules set by each state, says Dayna Kelly, ’91, founder of an eponymous law firm in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. For instance, in the past, California would not grant waivers to specialists—even physicians who worked in medically underserved regions or medical specialties. Recently, the state began accepting specialists, but waits until late in the application process—after most applicants would like to know where, and if, they will be working.

“Since each state can set its own program rules, my work includes building relationships with the state department of health administrators and working on ensuring that their rules and conditions make sense,” says Kelly. “It’s very satisfying when I can help programs change for the better. One example is North Carolina, which used to have a four-year requirement. Now it’s the standard three years.”

The system can be so difficult to navigate that some large medical institutions employ lawyers who specialize in this area. Chris Wendt, ’98, is the in-house immigration lawyer for the Mayo Clinic, which has major campuses in Minnesota, Arizona, and Florida, as well as dozens of locations in other states.

“It’s a patchwork of state and federal rules. It’s hard to explain to physicians, who think logically, why you can’t do things in certain states. It’s especially difficult because these are people who sincerely believe that what they want to do is in the best interest of patients,” says Wendt.

While it can be frustrating, Wendt says, he also understands the need for limits and for having a process through which foreign nationals must apply to stay in the country. After all, he says, the physicians came to the States for graduate medical education “knowing that they have this two-year homestay requirement.”

The need for foreign-national physicians will only continue to grow, particularly under provisions of the Affordable Care Act that emphasize primary care, the three alumni predict. Harris hopes that the process becomes more streamlined for these international physicians who are trained in the United States. “My hope would be that we could be open to a much more transparent and time- and cost-effective method of adjudicating health care providers in the future,” she says. “I hope there will be continued bipartisan recognition that we have to increase graduate medical education slots within the United States and that money will be put into that, so that quality health care can be provided for more people in this country.”

Kelly points out that the physicians often benefit the places where they work long after they have satisfied the requirements of their waivers. After they have had H-1B status for three years, some of them get Green Cards and then apply for citizenship. “I see that the doctors who come to these communities tend to stay in the communities. They raise their children there. And it’s not just in rural areas; it’s in all places where there just aren’t enough physicians to treat the needs of the community.”