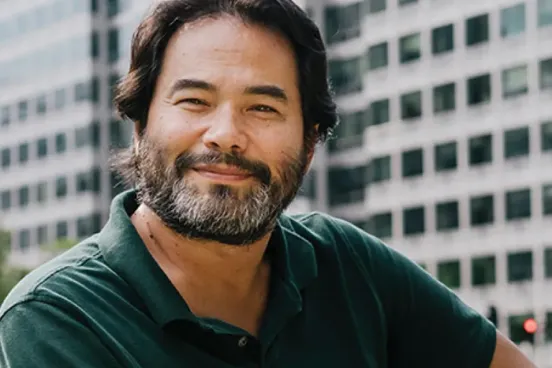

“My overarching goal is to help transform mental health care worldwide. It’s broken everywhere, and it is a global problem,” says Craig Kramer, ’87, Johnson & Johnson’s (J&J) first mental health ambassador. But raising awareness about and erasing the stigma of mental illness were not part of his plan as a Michigan Law graduate—nor was it where he started.

After graduating from the Law School, Kramer worked as a staff attorney with the International Human Rights Law Group in Korea, monitoring its landmark presidential election and issues like freedom of the press and the treatment of political prisoners. In Seoul, he got a taste for working in international affairs and politics, but when he returned to the States in 1988, he entered private practice in Washington, D.C.

At Patton, Boggs & Blow, Kramer represented clients in international trade, tax, antitrust, mergers and acquisitions, and class-action cases before all three branches of the U.S. government. His nearly six years there helped him land his next job. As Congressman Sander Levin’s deputy chief of staff, he handled bilateral and multilateral trade negotiations, since Levin was then the ranking Democrat on the House Ways and Means Committee.

In 1998, he left Capitol Hill to join J&J as director of government affairs and policy, overseeing U.S. trade and tax policy and chairing its federal political action committee. In 2002, he became executive director. “I was the fifth J&J government affairs professional based in Washington, D.C. Half of our sales were international, so I suggested expanding our presence in other countries.”

Kramer spent much of the next 17 years creating the company’s international division of government affairs and policy, leading teams in the Western Hemisphere and Asia-Pacific. “It was a pretty heady career to work with world leaders and patient and industry groups all over the globe as they confronted the social and financial impacts of cancer, diabetes, HIV, and infant and maternal mortality and care.”

Then, in 2013, things abruptly changed when Kramer’s daughter, who had an eating disorder, attempted suicide. The ubiquity of mental illness hit him hard, which he discussed in his speech at the B7 Summit in Canada in 2018. “The most important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see, and it often takes the fresh eyes of a younger generation to clearly see those realities. Such is the case with mental health.”

Kramer learned that mental health care costs more than cancer, diabetes, and respiratory diseases combined—half of the economic burden of all chronic illnesses worldwide. “I had thought my family was uniquely unlucky,” Kramer says. “But every family is touched by this because one in four people has a diagnosable mental health condition. The stigma, shame, and ignorance keep most people from talking about it, so we don’t realize just how big it is.”

As Kramer traveled around the world for his job, he asked health ministers, prime ministers, and hospital CEOs about mental health care in their countries. “I found out it was the same everywhere—broken. In fact, the World Health Organization now says that when it comes to mental health, every country is a developing country,” he says.

In response, Kramer worked with J&J leadership to create the mental health ambassador position three years ago to work on mental health issues with J&J employees and industry, civil society, and government leaders. He spent the first three years in the role building global coalitions to raise awareness about the number of people impacted by mental health disorders and to forge an increased investment in research.

“We are hoping to get significant funding for research and for insurance coverage over the next year or two. We also want to project a clear message about mental illness,” he says. “It’s very common, part of the human condition, and it’s very treatable. We really feel like we’re at an inflection point on the scientific and social-cultural pathways in this movement, and we are hoping to leverage that to drive the system change that’s required.

“The world we are all trying to create,” he adds, “is one where everyone can hug their daughter, like I did every time I visited Katharine in Ann Arbor when she was pursuing her master’s in social work at Michigan. She’s the real hero in this story. Everyone has the right to live a full and meaningful life like she is today.”