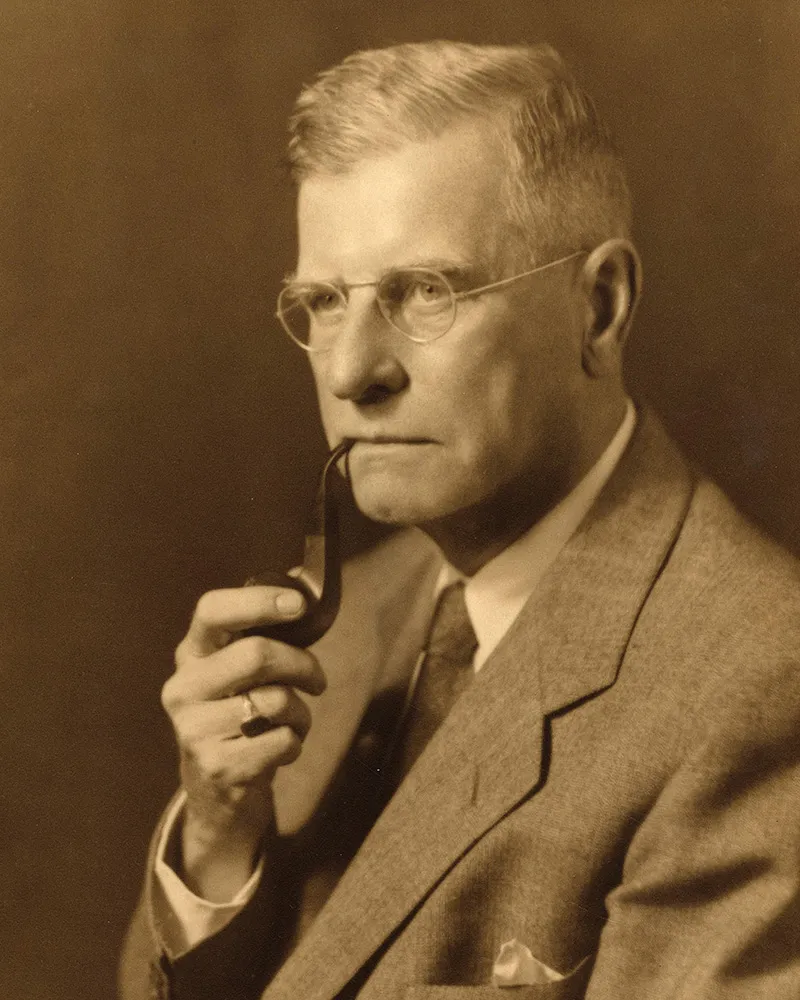

In the early 20th century, Edward S. Rogers was a prominent and influential lawyer. He led two law firms, litigated high-profile cases, wrote and spoke widely—and taught for years at his alma mater, Michigan Law.

Although not well known today, Rogers left an enormous legacy. He spent decades crafting the language for what would become the 1946 Lanham Trademark Protection Act—and persuading Congress to enact it. Seventy-eight years later, Rogers’s language is still the cornerstone of US trademark law.

Jessica Litman, the John F. Nickoll Professor of Law and an expert in copyright and trademark law, has contributed a chapter on Rogers to a new book, Robert G. Bone and Lionel Bentley’s Research Handbook on the History of Trademark Law.

“Rogers is unquestionably the most important historical figure in United States trademark law, but he isn’t currently famous,” Litman says. “I’ve been an Edward Rogers fan for 42 years. He’s a distinctive and distinguished alumnus, and we ought to be very proud of him.”

Litman—who has co-authored (with Jane Ginsburg, Mary Kevlin, and Rebecca Tushnet) the casebook Trademark and Unfair Competition Law: Cases and Materials—first became fascinated with Rogers when she was a law student, and her interest in his work has been cited twice in US Supreme Court cases.

Jessica Litman, the John F. Nickoll Professor of LawRogers is unquestionably the most important historical figure in United States trademark law, but he isn’t currently famous…He’s a distinctive and distinguished alumnus, and we ought to be very proud of him.

An early start on trademark law

In a way, Rogers’s career and US trademark law grew up together.

As recounted in Litman’s book chapter, Rogers was born in Maine, and he graduated from the Orchard Lake Military Academy after his family moved to Michigan. His first degree from Michigan Law, in 1895, was an LLB—earned in a two-year undergraduate program, and essentially a precursor to today’s JD. He would later return to Michigan Law to earn an LLM and a PhD as well.

As a student, Rogers attended lectures on copyright law delivered by Chicago attorney Frank Fremont Reed—a U-M (though not a Law School) alumnus who played on Michigan’s first football team—and after graduation, Rogers went to work at Reed’s firm. The two developed a practice in the developing field of trademark law, and a few years later, they split off to open their own firm, Reed & Rogers. Later Rogers would also co-found Rogers, Ramsay & Hoge in New York, practicing with both firms simultaneously.

As a litigator, Rogers tried a series of major trademark cases for clients including Coca-Cola, Bayer Aspirin, Kellogg’s, and the Merriam Webster Dictionary Company. “He was a gifted oral arguer, and he had a talent of explaining that his position was the sensible position and any other position was not sensible. Judges, senators, and representatives complimented him on that ability,” Litman says. “So he won, more often than not.” He also wrote extensively on trademark and copyright issues.

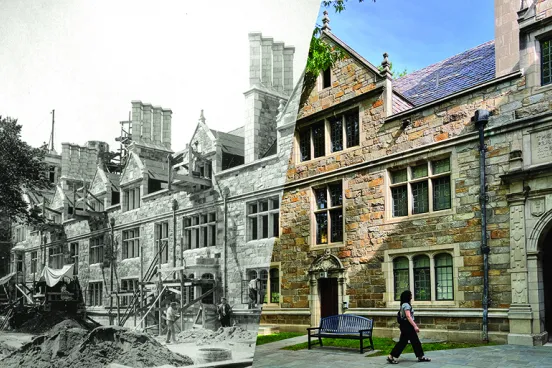

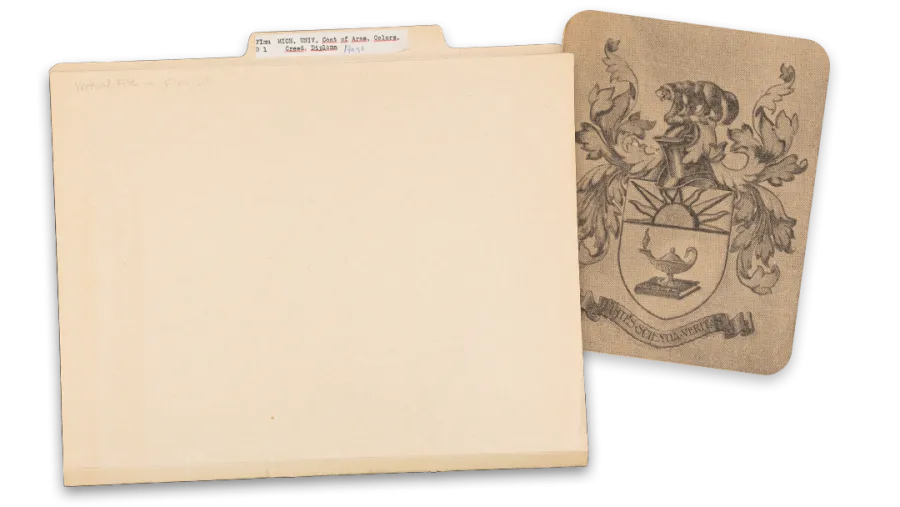

In addition, Rogers found time to teach, returning to Michigan Law as an adjunct faculty member in trademark and copyright law for 18 years. Somewhere along the way, he took it upon himself to commission a design for a coat of arms for the University of Michigan, and it was displayed in the Michigan Union for years. “He was really interested in heraldry because it was sort of the trademark of the gentry back in Europe. It was a trade symbol in much the way contemporary trademarks are,” Litman says.

Yet all this activity took place alongside Rogers’s greatest professional achievement: authorship and eventual passage of a core US trademark law, an effort that took decades to succeed.

An act of a lifetime

As Litman recounts in her chapter, Rogers’s authorship of the Lanham Act began with a 1914 article in the Michigan Law Review criticizing the current trademark registration law. That led to a well-received American Bar Association speech, followed by an invitation to return with a proposed new bill.

Two key elements of Rogers’s draft bill were a continued reliance on common law authority, which had traditionally governed US trademark law, and one big exception to it: creation of a civil action for willful use of any “false trade description.” Litman calls this “a significant departure” from extant common law, and it was an idea that ultimately survived in the approved Lanham Act.

Litman describes how the following years saw numerous presentations, amendments, rewrites, and occasional competition to Rogers’s bill. A version was introduced in Congress in 1924—with 18 other versions introduced in later years—but things like the Great Depression, the New Deal, World War II, political pressure, and simple inertia got in the way.

Ultimately, “the Supreme Court grew disenchanted with the idea of a national general common law, which they thought made so much sense in the 19th century,” Litman says. “That change unmoored the legal basis of trademark law from its common-law foundations. So I think that is what finally spurred people to get behind some kind of statutory solution.”

Even so, it would take several more drafts before Congress would pass the Lanham Act in 1946. By then, Rogers had retired from active practice, but the approved version was mostly his work. He died three years later, at his home in Greenwich, Connecticut, at age 74.

Influence and impact

Litman first learned about Rogers as a student at Columbia Law School in 1981 while writing a note on a trademark question. “I read all of the hearings relevant to the 1946 Lanham Trademark Act and discovered Edward Sidney Rogers,” Litman says. “It seemed to me it was quite unusual that this young lawyer from Chicago had written this draft statute, and he was coming back every year and trying to talk the House and the Senate into enacting it. I made a ton of notes, and I still have them.” The US Supreme Court cited Litman’s student note, published in the Columbia Law Review, a few months later in Inwood Laboratories v. Ives Laboratories.

In 2021, Litman spoke at a symposium celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Lanham Act. That led to a second Supreme Court citation tied to her work on Rogers, in a concurrence in Vidal v. Elster, decided earlier this year.

“When I was invited to contribute a chapter to a collection of trademark history essays, I hauled out my 40-year-old notes and read or reread all of Rogers’s published writings, all of his litigated cases, many of his briefs, and all of the congressional hearings,” Litman says. “With the Law Library’s help, I was able to do additional research to fill in historical details of Rogers’s life and the lives of the other people in the story.”

Litman’s chapter notes that one of Rogers’s main goals in writing a trademark law—preserving the legal protections offered by the common law of trademarks and unfair competition—was not only realized at the time, it still holds true.

“The Lanham Act was very much Edward S. Rogers’s story, and what made it into the trademark act was very much a product of what he thought should go into it,” Litman says. “Now here we are, 76 years later, and the trademark statute is essentially unchanged from the statute he wrote and Congress enacted in 1946. This is an individual who really has shaped our trademark law.”

According to an article in the 1931 Michiganensian, Edward Rogers was inspired to commission a university coat of arms as a way to decorate the dining room at the University Club of Chicago. Working with the College of Arms in London and a professional heraldic painter, Rogers developed a design based on the university seal but adding “mantling” on the sides, a helmet, and a wolverine crest. (The English designer being unfamiliar with Michigan’s mascot, Rogers reportedly asked him to create a “sort of brunette badger.”) Rogers then had an expert in heraldic carving create two versions of the design in wood—one of which went to the University Club, and the other hung for years in the Michigan Union.