As Mary Frances Berry, ’70, walked along a Nashville street in 1954 with her high school history teacher, she passed a newspaper headline that read: “Segregation Must End.” The Supreme Court had just ruled in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case.

Berry experienced segregation firsthand: segregated buses, restaurants, drinking fountains, and more. She knew that to watch a first-run movie, she had to go down the alley and climb a seemingly endless number of stairs to reach the cramped top balcony of the local theater—the crow’s nest, it was called—while white members of the audience sat on the main floor. When Berry saw the headline, she looked at her teacher and asked if it meant that white and black children would go to school together the next year.

“Not so fast, Mary Frances. Not so fast,” the teacher said.

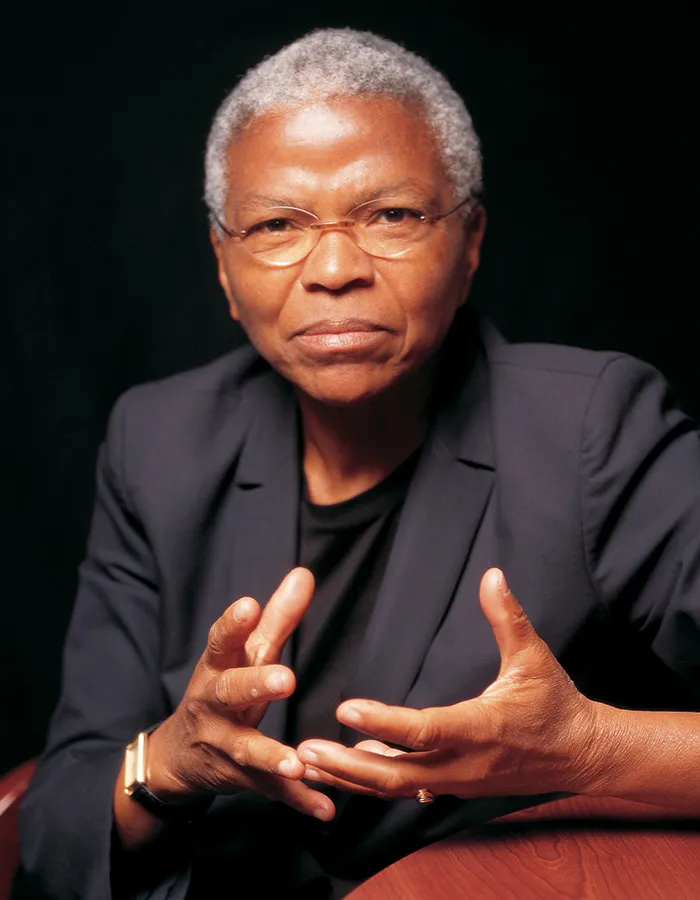

The advice went largely unheeded, as slowing down has never been Berry’s strong suit, especially not when it comes to helping end discrimination and foster advancement opportunities for underrepresented populations in the United States. Berry served from 1980 until 2004 on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, including as chair. Later, she stood with Nelson Mandela to end apartheid in South Africa and was imprisoned for it.

Here, at the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, Berry looks back on her productive—and hard-fought—career, her accomplishments, and the long list of items still outstanding in the fight to end discrimination.

A Legacy of Achievements

Berry was a trailblazer at the outset.

After graduating from Howard University in 1961, she came to U-M for graduate work and completed a PhD in history in 1966, a JD in 1970, and, by 1976, was chancellor at the University of Colorado, Boulder—the first black woman to head a major research university. Shortly after, she was appointed by President Jimmy Carter as the assistant secretary for education, becoming the first black woman in that position.

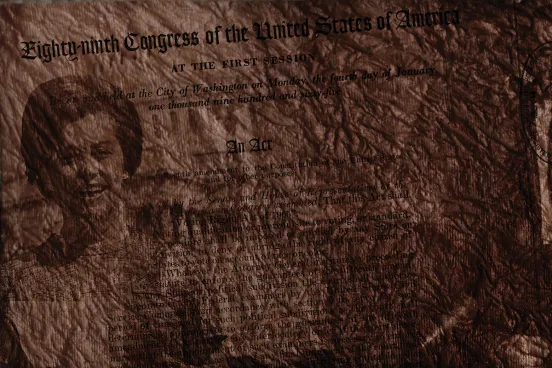

President Carter appointed Berry in 1980 to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, a bipartisan agency that monitors the enforcement of civil rights laws. It was an important place from which Berry could help inform a dialogue about race in the United States. As she explains in her 2009 book, And Justice for All (Knopf): “After conducting fact-finding investigations and studies, the Commission recommended much of the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the language minority protections of the Voting Rights Act passed in 1975, [and] the Age Discrimination Act of 1978.”

Berry was determined to continue the legacy of achievements. She got to work, but soon President Reagan attempted to dismiss her and to fill the Commission with his own appointees. Berry sued to keep her place, won, and later was made chairperson under President Clinton in 1993. The commission continued its work, helping secure passage of the Disabilities Act of 1990 and the Civil Rights Act of 1991, and investigating fraudulent voting charges in Florida in the 2000 presidential election.

Berry left the Commission in 2004 and says that, after her departure, the group’s role changed. “The Commission stopped supporting strong enforcement of longstanding civil rights laws,” she writes in And Justice for All. She argues that instead of taking action, the group instead criticized remedies for discrimination, such as changes in laws or policies.

“It’s not a question of whether discrimination still exists,” says Berry, noting the Commission agrees that discrimination is alive and well, “but the Commission has been more interested in undermining the concept that there should be remedies for discrimination. They think that all discrimination is something that happens to an individual, not a group.”

For its part, the Commission may be changing more to Berry’s liking, though probably not as quickly as she would like. In 2011, President Obama appointed two new commissioners: Roberta Achtenberg; and Martin R. Castro, ’88, now the chair. Both received praise from the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, which just two years prior had issued a blistering report about the Commission’s ineffectiveness, as well as a list of recommended reforms.

In July 2014, the Commission released a statement reflecting on the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, saying “more work remains to be done to assure the purpose of the Act and the purpose of our Union are achieved for all Americans.” This, the statement said, includes protecting against not just racial discrimination but also preserving voting rights and the protection of same-sex couples.

Berry’s work and advocacy in the years after her time on the Commission has included the writng of numerous books, most recently Power in Words: The Stories behind Barack Obama’s Speeches, from the State House to the White House with Josh Gottheimer (Beacon Press, 2010). During her career she has received 35 honorary doctoral degrees along with prestigious awards including the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins Award, the Rosa Parks Award of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Ebony Magazine Black Achievement Award.

Since 1987, Berry has been the Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and professor of American history at the University of Pennsylvania. She still actively teaches courses such as Law and Social Change in Modern America while also advising undergraduates.

It is perhaps her role as teacher and historian that has her using the long lens of history to explain how civil rights in this country has changed since the Civil Rights Act of 1964. She points, for instance, to the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case. Berry says she knew right away that Bakke would have a “chilling effect” on affirmative action efforts, and that the decision “refused to use the history of slavery and discrimination to uphold targets or goals.

“It was clear to me that on an issue like civil rights and affirmative action, the people who were hostile to doing anything to increase the number of black students on our campuses anyway could use this as a cover,” Berry says. “When the U.S. Supreme Court says that you may do something, it also means you may not do whatever it is. Leaving it up to people’s discretion, I knew, would not be good enough, and in a thousand campuses where those decisions were being made, people could say, ‘Well, you know, we’d like to help you, but look at the Bakke case.’”

U-M, of course, has been central to the post-Bakke debate on this front, with the Supreme Court’s 2003 Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger rulings, and the later ballot initiative, Proposition 2, which made race-based admissions illegal in the state of Michigan.

The court’s ruling, and the grassroots petitions that later reversed it, highlight an underlying problem, says Berry: the tension between the idea that the United States is a post-racial society, and the reality that it isn’t.

Beyond Discrimination?

Berry points out that some people will contend that the country is “post-racial” and no longer needs to uphold laws from 1964, the year the Civil Rights Act was signed into law.

“It is indeed true that when Obama was nominated and elected, many people in the media and in the public talked about how we’d become post-racial and had moved beyond discrimination,” Berry says. “But there is sufficient evidence from cases, quotes, and episodes around the country that show that is not the case.”

She points to the education disparity in the country as well. “We do know that the dropout rates and push-out rates from middle school to high school and non-graduation rates are disproportionately black and Latino students.” There’s also the issue of employment. “The percentage of unemployed in this country is higher now than when the Civil Rights Act passed [in 1964]. That has effects on individuals and families—everything from stress to resources. It’s something that poor whites face, but it disproportionately affects higher numbers of blacks and Latinos.”

In her mind, there are many issues still to be rectified, but she holds out hope that a new generation of leaders—the next Rosa Parks, the next Martin Luther King Jr., the next Cesar Chavez, she says—will rise up.

“There are all kinds of young people who are trying to make change and learn,” she says, citing several groups across the country working with women, HIV patients, and, of course, university students fighting the status quo.

“On campuses all across the country, you’ll find young leaders who are stepping up and making change,” she says. “I’ve been trying to pass the torch for years, and I’m still trying, but I don’t doubt that there will be people who will step up and move.”