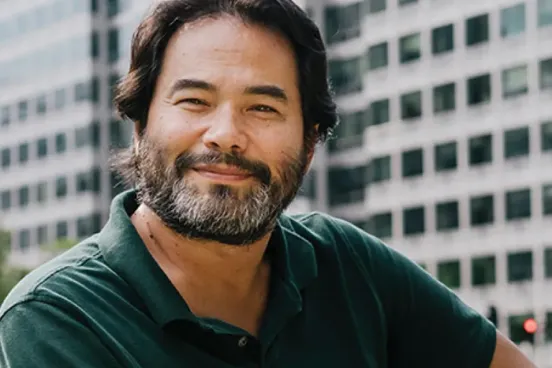

It is 2018. Not using or being affected by the Internet today is as feasible as shutting out the entire world. With the digital age taking off around us, Breanna Van Engelen, ’14, is fighting a new wave of criminals.

A civil trial litigator in Seattle, Van Engelen specializes in technology and privacy—an interest stemming from her time at Michigan Law. “I was fascinated by Professor [Jessica] Litman’s view on using copyright statute to help victims of non-consensual pornography get their images removed from the Internet,” says Van Engelen. “It is an issue facing hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Americans right now.”

Which was why, on her second day with K&L Gates, Van Engelen joined the firm’s Cyber Civil Rights Legal Project—a pro bono effort using creative legal theory to help victims of nonconsensual pornography.

“This is an area where the law hasn’t caught up to people’s conduct, and where victims have limited access to legal counsel,” says Van Engelen. “It takes real people on the ground, working every day as a team, to bring a cybercriminal to justice.”

Within several weeks of Van Engelen joining the initiative, one of its biggest cases walked through the door: Allen v. Zonis. Van Engelen’s clients, Courtney and Steven Allen, were suing Todd Zonis for cyberstalking and harassment that began when Mrs. Allen broke off an online relationship with Zonis that had involved explicit conversations and videos of a sexual nature.

Van Engelen’s work in and out of the courtroom unwound the Allens’ tangled tale—and Zonis’s claims that he, not the Allens, was the victim—and ultimately presented an argument that resulted in an $8.9 million jury verdict for the Allens.

It was a record-setting cyber harassment verdict for a case not involving a celebrity. “Every day, I felt for the Allens and what they endured,” says Van Engelen. “It pushed me to go above and beyond. I did what I had to because I knew we were on the right side.”

With limited technical experience outside of what she learned for the case, Van Engelen spent free time studying cyber forensic textbooks and anonymizing software.

“Catching a cybercriminal takes a level of motivation that goes beyond billing hours,” she says. “You have to follow every lead, powering through the evidence, to catch them in a mistake.” Van Engelen painstakingly searched until she found the one login where Zonis—who denied much of the harassment—forgot to use the Tor browser that helped him move anonymously online.

While it was clear to Van Engelen who deserved justice, she had to convince the jury to look beyond her client’s extramarital cyber affair.

“I was worried they wouldn’t forgive her and would blame her for making the videos that Zonis later sent to others,” says Van Engelen. “But the torment she, her husband, and child faced on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis…it was so disproportionate.”

In order to break this perception that Mrs. Allen’s behavior enabled the crime, Van Engelen used the teachings of Michigan Law Professor Marshall Goldberg, to create a narrative that was truthful, compelling, and resonated with the jury.

“Jurors are human beings with real-world experiences, and I knew they would have the empathy and compassion to do the right thing,” says Van Engelen. “I wouldn’t have had these skills—nor this success—had I not taken his class.”

Even though Allen v. Zonis was a landmark verdict, it will take more of its kind before the law catches up to technology. “Action needs to be taken on state and national levels, giving cybercrimes felony status,” says Van Engelen, who continues to advocate for the law to change but foresees it ultimately happening at the hands of juries.

“In many ways, juries are more ready than the law to hold cybercriminals accountable. Jurors understand we aren’t living in a puritanical world anymore and this kind of conduct isn’t acceptable.”

![The Tech [R]evolution in Law The Tech [R]evolution in Law](/sites/default/files/styles/teaser/public/2023-03/The-Tech-%5BR%5Devolution-in-Law.jpg.webp?itok=Obrll94p)