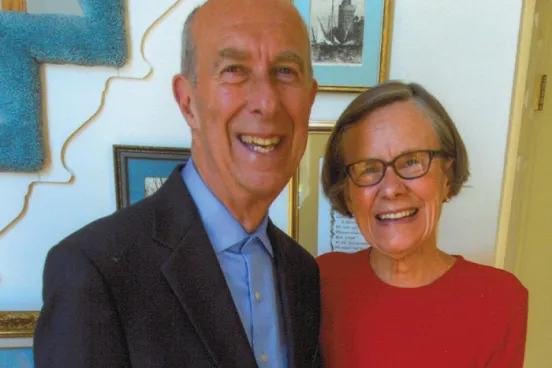

Roger Wilkins exposed injustice and fought for equality—through the complex lens of being a black man in America—throughout his career as a public servant, educator, and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist.

“I don’t think we’re ‘Africans in America,’” Wilkins, ’56, said in a 1997 speech at U-M. “At least I’m not. What kind of African is born in Kansas City; lives and dies for the University of Michigan football team; loves Toni Morrison, William Faulkner, and the Baltimore Orioles; reveres George Washington and Harriet Tubman; and who, when puzzled by the conundrum of Thomas Jefferson, collects his thoughts while listening to B.B. King?”

In honor of Wilkins’s vast and varied accomplishments, the Law School is honoring him as its 2014 Distinguished Alumni Award recipient.

Wilkins came of age intellectually and professionally during a watershed time in American history: The Brown v. Board of Education ruling was handed down while he was in law school. “Sixty years later, we all appreciate that Brown unleashed a movement that … affected profoundly many aspects of American life,” said Wilkins, the Clarence J. Robinson Professor Emeritus at George Mason University.

In his early days at Michigan Law, Wilkins was confronted with the fact that race helped define how others saw him.

In his autobiography, A Man’s Life (Ox Bow Press, 1982), he recalled meeting with a professor who said that although Wilkins had a subpar academic record, the Law School had admitted him because his undergraduate professors had vouched for the quality of his campus involvement. The professor then said the Law School felt strongly that it had a responsibility to help produce strong black leaders.

“That doesn’t mean you won’t have to do the work,” Wilkins recalls the professor saying, “but that’s why we took a chance [on you].” Wilkins answered the challenge by graduating with a far better academic record than he held as an undergrad.

His first formal work with civil rights was as a rising 3L intern at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, under then Director-Counsel Thurgood Marshall. A commitment to social justice ran in Wilkins’s family: His uncle, Roy, was executive secretary of the NAACP; his father was a well-respected black journalist; and his mother worked to integrate the YWCA.

After graduating from Michigan Law, Wilkins became a caseworker for the Ohio welfare department.

He later served as an assistant attorney general in the Lyndon Johnson administration, in charge of the Justice Department’s Community Relations Service.

He explained his commitment to the public sector in a 2011 NPR interview: “Can I stand around with my two degrees from the University of Michigan and watch other people do the changes? I couldn’t be a bystander.”

“Can I stand around with my two degrees from the University of Michigan and watch other people do the changes? I couldn’t be a bystander.”

At that time, Wilkins was one of the highest-ranking black Americans ever to serve in the executive branch, and as head of the Community Relations Service, he was the White House’s emissary to peacefully resolve the 1965 Watts riots in Los Angeles.

“One of the worst things … was the fact that important Angelenos, who should have known about the conditions in Watts, were seeking interviews with us about conditions in their own town,” Wilkins wrote in a 2005 Washington Post op-ed.

He had seen firsthand the power of the press; his father was the only black journalist to interview presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt, and his father and uncle both worked for a prominent black newspaper.

So after Johnson left office, Wilkins became a journalist, first at The Washington Post, then at The New York Times (where he was the first black person on the editorial board), the Washington Star, and National Public Radio.

In 1972, as a member of the Post’s editorial staff, he shared the Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Watergate scandal with Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein, and Herbert Block. He also was the publisher of the NAACP’s journal, The Crisis.

As he reflects on a career that spans from race riots to the election of the first black president, Wilkins notes the fight for racial justice is not over.

“Michigan Law gave me the analytical tools and skills I needed to push these struggles forward as a lawyer, journalist, and professor, and I know that it will do the same for many others. I am truly honored to be receiving the Distinguished Alumni Award from the institution that helped me to become the person I sought to be.”