Think of everything you’ve heard about Detroit Public Schools in recent years: gym floors buckling, walls covered in toxic black mold, archaic math books scattered around the classroom floor of an abandoned school. A state bailout and restructuring plan. Teacher shortages, fraud charges against suppliers, and what The New York Times described as a “chaotic mix of charters and traditional public schools,” in which students in many charters as well as traditional public schools lag behind in testing and other metrics.

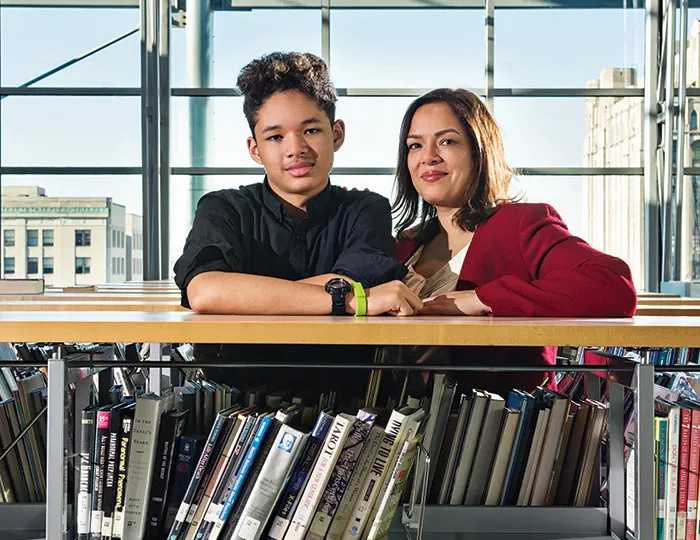

Now set those ideas to the side for a moment, and meet Stephen Chennault III, known as Trey. He is a freshman in high school, and very bright. He is really interested in engineering and thinks about attending U-M, UCLA, and other top universities. He attended private schools until last year. Then, he and his mother, Kimberly James, ’96, searched for the high school that would fit his skills and ambitions.

They chose a public school in Detroit: Cass Technical High School. “I think there might be a perception of a Dangerous Minds kind of environment,” James says, referring to a 1995 movie about a tough inner-city school. “But I’ve been quite pleasantly surprised with the level of interaction we have with the teachers. They’re very responsive, and they’re very invested in their students doing well.

“I’m also glad that Trey can have a more traditional high school experience than he could have at a smaller private school. This was the best choice for him, academically and socially,” she says. At Cass Tech, Chennault is on a curricular pathway for engineering; this year, he has been learning drafting and planning, and he will advance to computer-assisted design (CAD) software courses, among others.

How could it be that a public school in Detroit was the best choice for Trey? The answer lies in the complexities of a school district that is tattered but not completely broken, where some bright spots shine against a tableau of uncertainty—a school district that is a microcosm of challenges faced by public schools across the nation.

Steven Rhodes, ’73One of the goals I had was for the district to take control of its narrative.

Out of Retirement, into the Fire

The Hon. Steven Rhodes, ’73, had retired from the judiciary after a career that included overseeing the case that led the City of Detroit out of bankruptcy. He could have taken a vacation, or several, and enjoyed the tranquility of retired life. Instead, he accepted the offer when Gov. Rick Snyder, ’82, asked him to be the short-term transition manager for Detroit Public Schools (now known as the Detroit Public Schools Community District, or DPSCD).

His task would be to balance the books and begin improving schools that serve 48,000 students— down from more than 160,000 students in 2000, due to demographics, the movement of some 34,000 students to charters, and the State-run Education Achievement Authority’s takeover of former public schools. A turnaround would be no small feat for a district that had closed dozens of schools and had accumulated deficits of more than $500 million in recent years, and where state-appointed emergency managers had struggled.

Rhodes came into the almost-yearlong role in early 2016 with a solid understanding of the challenges but also with optimism about the district’s future. “One of the goals I had was for the district to take control of its narrative,” Rhodes said during an interview with the Law Quadrangle on his last day as transition manager in December. “Lots of people speak about public education in Detroit in ways that aren’t always accurate. The narrative that I think is accurate is one of a fresh start, of restructuring, revitalization, and reorganization. And a narrative of being on a path to a successful future.”

That path is complicated by numerous factors. One is the mix of public schools and charter schools. Detroit has the second-highest percentage (after New Orleans) of students in charter schools of any city in the United States. State taxpayers fund charter schools throughout Michigan with nearly $1 billion a year, much of which would go to public schools in a traditional model. To be sure, some charter schools have been successful and have created what many see as necessary competition for public schools. At many charter schools in Detroit, however, test scores and other measurements indicate little or no benefit over traditional public schools.

“While the idea was to foster academic competition, the unchecked growth of charters has created a glut of schools competing for some of the nation’s poorest students, enticing them to enroll with cash bonuses, laptops, raffle tickets for iPads, and bicycles,” a recent New York Times analysis stated. “Leaders of charter and traditional schools alike say they are being cannibalized, fighting so hard over students and the limited public dollars that follow them so that no one thrives.”

Nationwide, much of the debate about the impact of charter schools on traditional public schools references Michigan as a case study. Researcher David Arsen, a professor in the Department of Educational Administration at Michigan State University, published a widely cited paper in 2016 titled “Which Districts Get Into Financial Trouble and Why: Michigan’s Story.” Through their research, Arsen and his collaborators found that state school finance and choice policies “significantly contribute” to the financial problems of Michigan’s most hard-pressed districts, particularly Detroit.

“Most of the explained variation in district fund balances is due to changes in districts’ state funding, enrollment changes including those associated with school choice policies, and special education students whose required services are inadequately reimbursed by the state,” the study reports. “Our results show that the state’s school choice policies powerfully exacerbate the financial pressures of declining-enrollment districts, particularly those with sustained high levels of charter school penetration.”

The study came out in the summer of 2016, right around the time that the battle over charter schools in the state entered a new chapter. That’s when the Legislature passed and the governor signed a measure that did not include an education commission under the control of Mayor Mike Duggan, ’83. Many in the Detroit educational community had hoped such a commission would have been able to influence which new charter schools were allowed to open.

But the June signing did include a $617 million bailout for which Rhodes had pushed. “This legislation gives Michigan’s comeback city a fresh start in education,” Snyder told The Detroit News. “Now the residents of Detroit need to engage with their schools and help find good leaders who can provide the best possible chance of success for families in the city.”

Another challenge for the school district is the way Michigan allots per-pupil spending. Not every district receives the same per-pupil allowance. But each district does receive an allowance within a “statutorily defined range, theoretically ensuring a modicum of funding equality across the state.” In a 2016 opinion piece for mlive.com, Eli Savit, '10, who is senior adviser and counsel to Duggan, wrote, “The facade of equality collapses, however, when one realizes that Michigan funds only part of local school districts’ expenses. Crucially, Michigan provides zero funds for building new school facilities, or for improving or maintaining older schools. Whenever a district needs to replace or refurbish an aging school building, it must raise the funds itself. And as a practical matter, Michigan provides school districts just one way to pay for physical infrastructure: through local property taxes.”

Savit says the problem—as with any system based on local property taxes—is that wealthy districts are far better equipped than poorer ones to raise the necessary funds. In Bloomfield Hills, for example, the average home value is about $400,000. In Detroit, it is closer to $40,000. Detroit must levy a property tax 10 times higher than Bloomfield Hills to raise the same amount, per home, for a school maintenance or improvement project. “The results are predictable,” Savit wrote. “Wealthy districts in Michigan are able to build and maintain modern buildings while imposing only a minimal tax burden. In poorer districts—where many residents struggle to make ends meet—the cost of raising funds for building and maintenance is prohibitively high. Thus, aging schools in property-poor districts often go unmaintained and unreplaced. And so students in those districts are forced to attend school in dilapidated, hazardous buildings.” (A bond issue passed by Detroit voters funded the new Cass Tech High School, Trey Chennault’s future alma mater, which opened in 2005.)

In spite of those challenges, DPSCD has begun maintenance and repair work at many schools, in addition to other improvements. “So much more is needed,” Rhodes says. “But we’re off to a good start.”

Rhodes remains optimistic about the district in general. He offered positive reviews of newly elected school board members (who include Sonya Mays, ’08). Several partnerships between schools and businesses or organizations hold promise, he says—such as one between the Detroit Medical Center and Benjamin Carson High School of Science and Math, where students have increased opportunities to learn nursing, chemistry, and other skills; and one that will begin in the fall, a partnership between the city, trade unions, and A. Philip Randolph Technical High School to teach skilled trades.

Rhodes also is proud that the interim academic superintendent, Alycia Meriweather, involved teachers to help draw up the district’s new academic plan, and he says one of the best parts of his experience as transition manager was getting to interact with teachers.

“It all begins with the dedication and commitment of the teachers,” Rhodes says. “The efforts they put in given the challenges they face are incredible. Sixty percent of our students come from family settings in poverty. That makes educating them very challenging.” So teachers feed students breakfast. They do laundry at the schools so students can go to school in clean clothing. They buy supplies and textbooks with their own money.

“One visible change during my tenure is the attitude and morale of the teachers,” Rhodes says. “For the first time in seven or eight years, we were able to give them a modest pay raise. It was not as much as I would have liked to have given them, or what they deserved, but it was something. I hope the district can continue to find ways to give them the resources they need.”

A Constitutional Right to to Literacy?

The lawsuit Gary B. v. Snyder lays out the problem in direct language: “Decades of State disinvestment in and deliberate indifference to Detroit schools have denied Plaintiff schoolchildren access to the most basic building block of education: literacy.”

The lawsuit was filed against Gov. Rick Snyder, '82, and other state officials in September 2016 on behalf of several students who attend schools in DPSCD as well as two who attended charter schools in Detroit. Leading the charge for the legal team was Mark Rosenbaum, director of Public Counsel Opportunity Under Law and previously, for nearly two decades, a professor from practice at Michigan Law. “For the last 15 years, the State has run the Detroit schools into the ground,” Rosenbaum said at a news conference where the lawsuit was announced. He said the State has an obligation to ensure that all Michigan public school students receive their fundamental right to literacy under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Evan H. Caminker, the Branch Rickey Collegiate Professor of Law and former dean of Michigan Law, is a member of the legal team Rosenbaum assembled. Caminker knew at the outset that schools in Detroit were in disrepair and that students faced countless challenges, but he didn’t know the extent of the adversity until he delved further into the details of the lawsuit. The suit argues that the schools named “are schools in name only, characterized by slum-like conditions, and lacking the most basic educational opportunities that children elsewhere in Michigan—and throughout the nation—take for granted. Plaintiffs sit in classrooms where not even the pretense of education takes place, in schools that are functionally incapable of delivering access to literacy.”

Caminker, a constitutional lawyer, says, “What came as a surprise in a way that embarrasses me—I feel like I should have known this—is just how much the kids take [their decrepit school conditions] as a daily reminder that the only people who seem to care about them are the dedicated teachers. It’s hard not to react to the hand that they’re dealt and accept a life of despondency. They’re aware that they’re not getting what everyone else is getting. Some manage to rise above it. Some act out. Some fall into a timeless funk. But all of them take away the message that the State doesn’t seem to care about their education and well-being.”

Attorneys for the State of Michigan filed a motion to dismiss the suit in November, in which they countered that no constitutional right to literacy exists. “The United States Supreme Court and Michigan courts recognize the importance of literacy. …But as important as literacy may be, the United States Supreme Court has unambiguously rejected the claim that public education is a fundamental right under the Constitution. Literacy is a component or particular outcome of education, not a right granted to individuals by the Constitution.” A ruling on the motion is expected this spring or summer.

Caminker points out that the Brown v. Board of Education ruling emphasizes the importance of public school education to our democratic society, and that more recent Supreme Court decisions have held open the question of whether a state’s public school system must provide all and not just some students with access to minimum basic skills such as literacy. Constitutional lawyers who aren’t involved in the case, including Laurence Tribe of Harvard, have observed that Gary B. v. Snyder has the potential to be a landmark civil rights case, much like Brown was.

Caminker hopes that the lawsuit will lead to meaningful changes in the way that public education is provided, especially in major urban areas. “Detroit and school districts like it are so far below meeting the requirements for access to literacy,” he says. “We’re not asking for everybody to have a Cadillac. We’re asking for everyone to have access to more than a Flintstones’ car.”

Defending Traditional Public Education

Sonya Mays’s mother taught in Detroit Public Schools (DPS) for 30 years. Mays, ’08, attended schools in the district and later began her career as a substitute teacher in DPS. In 2013, she left a Wall Street job to return to her hometown, where she worked on the city’s successful efforts to emerge from bankruptcy.

While she was proud of the comeback in the central business district of Detroit, she grew frustrated with the lack of progress in the neighborhoods. So she led the creation of a nonprofit real estate company, Develop Detroit, which focuses on building opportunities around the city.

She also ran for a seat on the school board in the 2016 election, winning her seat in November. “I’m a diehard believer in traditional public education,” Mays says. “I tend to see it as one of the most progressive things the country has ever done. It represents the best of collective humanity, and it’s worth protecting.”

Kimberly James, '96, whose son, Trey, attends Cass Tech, also believes in the need for strong public schools. “I believe public education should be a fundamental right,” she says. “I’m hoping with the new school board there will be more accountability and oversight. It’s not going to happen overnight, but there is a lot of room for improvement.”

Mays adds that the influx of younger professionals into the city could benefit the school system, if they decide to send their kids to public schools. “They have to realize good schools cost money,” she notes.

In her first months as a member of the school board, Mays has visited several schools and met with many teachers and parents. She hopes board members can help to address the deferred maintenance, as well as find ways for teachers to have adequate resources. In March, Mays and fellow school board members filed a lawsuit on behalf of DPSCD against the State of Michigan over the State’s efforts to close 25 schools that have ranked in the bottom five percent academically for three straight years. The suit argues that the new district, which was just created in June 2016, should have a chance to reform the underperformers. “This lawsuit, at its core, is about clarity,” Mays says. “Does DPSCD have a fresh operational start or not?”

She also has learned more about the bright spots in the district that “don’t get heralded as much as they should,” Mays says. Among those are the top schools that historically have done a good job of educating students, such as Bates Academy, Renaissance High (the alma mater of Mays and Interim Superintendent Alycia Meriweather), Chrysler Elementary, and Cass Tech—which earned an “A” from the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in its 2016 Michigan High School Context and Performance Report Card.

Additionally, Mays points out that students in the district have one strong advantage, even while they face more challenges than students elsewhere: They are part of the Detroit Promise Zone, created by Mayor Duggan and City Council in 2015 to dedicate a portion of tax dollars to permanently fund two-year scholarships. In November 2016, the program was expanded to include scholarships at four-year colleges for students who meet GPA and admissions-test criteria.

In general, Mays says, “I see a clear path to not just stabilizing the school system but also reforming it in a smart way. I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t think that this system could and should survive.”