Azadeh Shahshahani, ’04, a prolific writer and speaker on the subject of immigrant rights, was first drawn to Project South because of the organization’s work to combat Islamophobia. “Project South organized one of the first initiatives in the U.S. South that provided support directly to Muslim families at a time when there was so much fear,” Shahshahani says, and it led her to approach the organization and eventually become its first attorney.

Based in Atlanta, she serves as Project South’s legal and advocacy director, and the organization now employs and supports movement lawyers who are focused on creating a legal infrastructure to help defend Muslim communities from state repression.

“Our end goal is to have a network of attorneys to support the work of the movement,” Shahshahani says. “We want to equip our community members, who are under daily attack and surveillance by the FBI and ICE, with strategies to not only move defensively against these violations, but to also push policies forward that protect the community.”

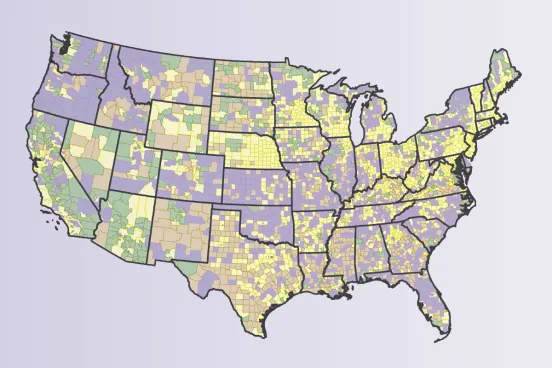

According to Shahshahani, immigrant and Muslim communities in southern states are not as organized as similar communities in other parts of the country, and Project South focuses on training and mobilizing more attorneys in the region, as well as educating the public at large on core issue areas affecting Muslim communities. This includes providing community members with the legal resources they need in order to know and invoke their rights; fight against surveillance, discrimination, and abuse; work against anti-immigrant and Islamophobic state legislation; document human rights violations at immigration detention centers and prisons and work towards shutting them down; and advocate for support for equal access to higher education and other fundamental human rights for undocumented immigrants.

These efforts have resulted in a “much better organized network of communities in the South, with more than 200 trained attorneys to continue the work,” Shahshahani says. Project South has also gained victories in the Georgia legislature, working against anti-sanctuary measures and dismantling a review board whose sole task according to Shahshahani was to penalize localities perceived friendly to immigrants.

But these gains haven’t been without their challenges, Shahshahani notes, and human rights injustices continue to occur at the local, regional, and national level, making it difficult at times to determine where to allocate Project South’s time and resources. “It’s hard to address all of these issues with the really limited capacity we have without burning out,” says Shahshahani. “It requires a lot of stamina.”

The changing legal and political landscape has also put pressure on Project South to simultaneously address current inequities and advance its goals. “It feels like you’re facing daily attacks,” said Shahshahani. “Every day, you’re in a defensive posture trying to deal with a new horrible development.”

Project South frequently partners with other organizations in the U.S. and internationally to address these challenges. One such example is the “People’s Tribunal: The People vs. Muslim Ban,” which was hosted by Project South and partners in Atlanta in 2017. Inspired by similar community-oriented tribunals hosted in the Philippines, Brazil, and Mexico, the forum allowed Atlanta community members to share their personal experiences with the Trump administration’s Muslim ban.

“It was a very powerful experience, and we were able to take justice into our own hands and provide a forum for affected communities who otherwise wouldn’t have had access to one,” she says.