William Yat San Chiang never met his grandfather, Pao Li Tsiang, ’23. Chiang didn’t attend the University of Michigan, and he has only visited campus once, so that he could see the place that helped shape his grandfather. But Pao Li’s legacy is important to Chiang, and he credits the University with securing that legacy. So Chiang recently made a $2.5 million gift to endow the Pao Li Tsiang Professorship Fund at the Law School—a fitting way to honor them both.

“My grandpa had a tough childhood. Without his education at the University of Michigan Law School, he would not have become a well-known lawyer, and my childhood would have been quite different,” says Chiang. “The impact we leave on future generations through emphasizing a good work ethic and education is far greater than passing on wealth. That is why I want to give back to the community and especially the University of Michigan, which has made a memorable impact on my life.”

With automobiles and airplanes still in their infancy in the early 1920s, it might seem unlikely that a former post office clerk in Shanghai would travel around the world to attend law school. But when Tsiang arrived in Ann Arbor, the University had strong ties with China dating back to when U-M President James B. Angell served as the U.S. minister to China in 1880 and 1881. In the ensuing years, U-M became a top U.S. destination for Chinese students, and the esteemed Soochow Law School (the Comparative Law School of China) in Shanghai, began sending its most elite law students to Michigan.

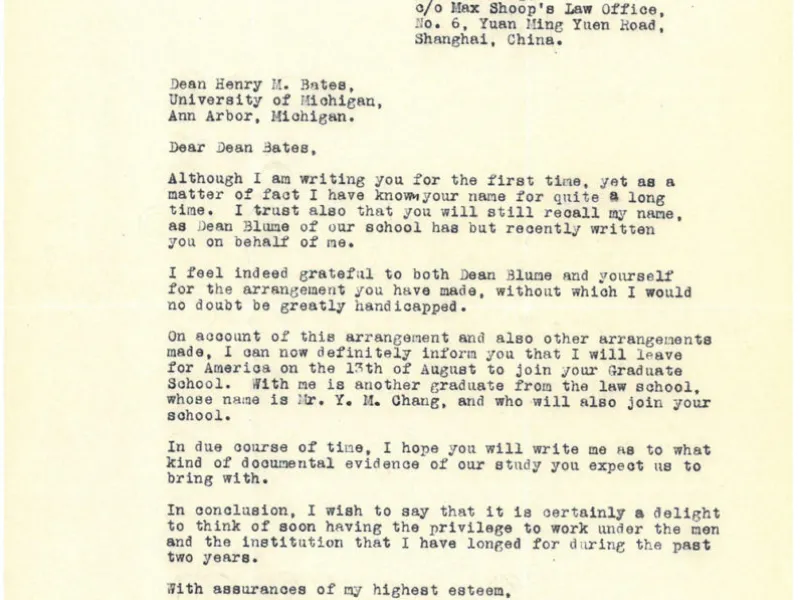

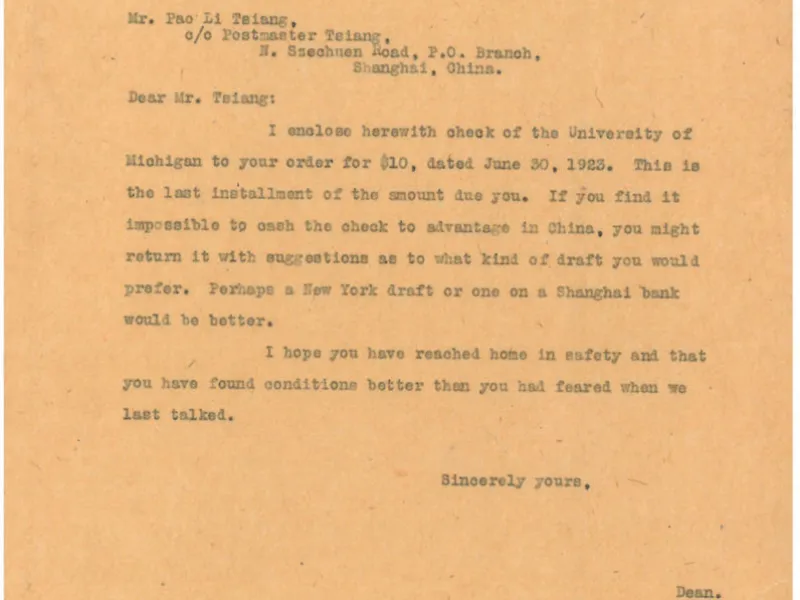

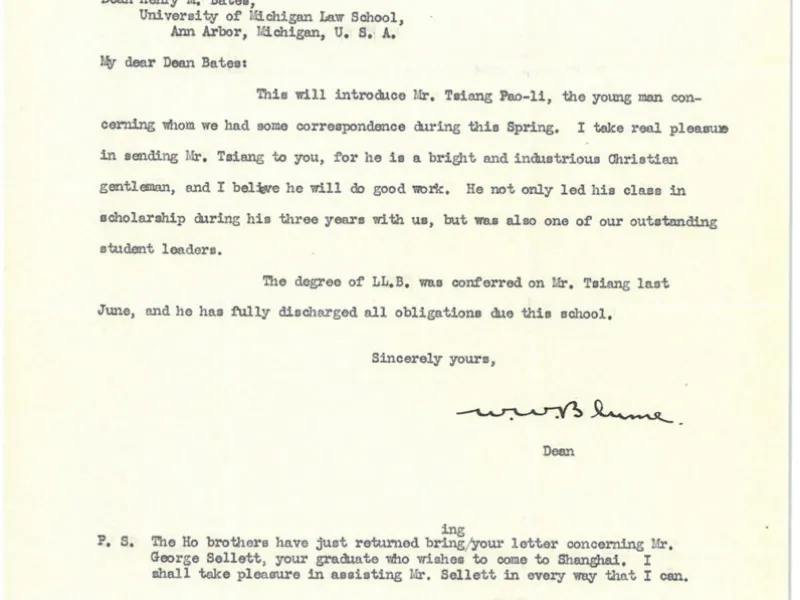

Pao Li Tsiang was one of them. Wanting to improve himself, Tsiang took evening classes while working at the post office in order to be admitted to Soochow Law School, where he earned a bachelor of laws. Soochow Law School Dean William Wirt Blume—who later earned JD and SJD degrees from Michigan Law and joined the faculty—recommended Tsiang to Michigan Law Dean Henry Bates. “I take real pleasure in sending Mr. Tsiang to you…. He not only led his class in scholarship during his three years with us, but was also one of our outstanding student leaders,” Blume wrote. After Tsiang graduated from Michigan and returned to Shanghai to practice law, Bates sent him several $10 checks to help him get his start.

As Tsiang’s law practice grew in the 1930s and 1940s, so did his stature. He became a professor at Soochow Law School and was a chief justice for the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, sentencing Japanese officials for war crimes perpetrated during World War II. He also became an adviser to Chiang Kai-shek and fled to Taiwan with the Nationalist government during the Communist revolution, leaving his wife and children behind.

Shortly after Chiang was born in 1951, his parents divorced, so he was raised by his grandmother (Tsiang’s wife), Zulan Zhang. With the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution, Chiang was forced to quit school and perform hard labor. “Grandma and I lacked food and clothes. It couldn’t have been more devastating, especially for a young man,” he says.

In 1979, Chiang immigrated to Hong Kong and apprenticed in a plastic mold shop. He leveraged his newfound expertise to launch his own business, which by the mid-1990s exported plastic products to the United States and Europe. Today he is the founder and chief executive of a baby care products business that enjoys distribution all over China, and he credits the lessons from the grandfather he never met with much of his success. “Grandpa was a disciplined person, and his emphasis on education inspired me. His values helped transform me.”

By endowing a professorship at the Law School, Chiang says he is supporting the root of his grandfather’s values. “Good education must come from great professors, just as a beautiful garden has to rely on the hard work of its gardener.”