Without a drop of gasoline, Tesla’s Model S goes from zero to 60 miles per hour in an electrifying 5.4 seconds. It’s sleek, state-of-the-art, and—owing to legislative efforts advocated by the car dealers’ lobby—noticeably absent from many American showrooms.

To antitrust authority and Michigan Law Associate Dean for Faculty and Research Daniel Crane, these efforts to bar Tesla Motors from directly distributing its vehicles to customers are “protectionist, pure and simple.”

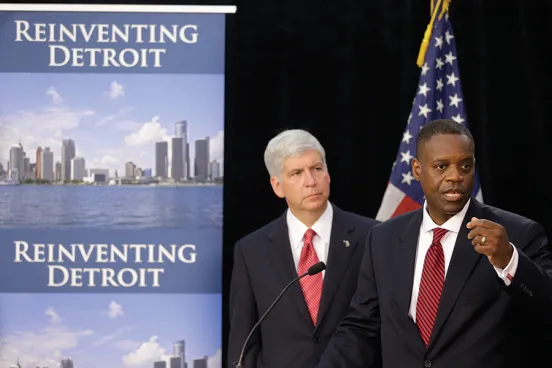

It is a view that has roused the ire of the aforementioned lobby just as it has garnered support across the political spectrum from many of the country’s leading economists and law professors—71 of whom joined Crane in an open letter (dated March 26) to Gov. Chris Christie voicing opposition to the New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission’s decision earlier this year to prohibit direct distribution of automobiles by manufacturers. Proponents of direct distribution suffered a similar setback in Michigan when Gov. Rick Snyder signed a bill on Nov. 21 that explicitly requires all automakers in the state to sell through a network of franchised dealers.

“A number of public figures and academics have entered the fray, arguing in favor of allowing Tesla direct distribution,” says Crane, whose own interest was spurred as a casual observer of the automobile industry. “I was fascinated by Tesla and how they would create the infrastructure around this new technology for electric cars. I wasn’t at all focused from a regulatory or legal perspective when I started following the news.”

But as reports developed of the state-by-state legal battles facing Tesla in its bid to directly distribute to consumers, Crane’s curiosity was piqued, and he began examining the car dealers’ arguments in detail.

“I had never really followed automobile distribution regulation and thought there might be legitimate arguments for why regulations should exist requiring the sale of cars through franchised dealers,” Crane says. “I started kicking the tires and found that the arguments flatly contravened everything that I knew of the economics of distribution. I no longer have any doubt that what we’re seeing here is pure protectionism on the part of dealers.”

Through a series of Truth on the Market posts, media interviews, and a working paper entitled “Tesla and the Car Dealers’ Lobby,” Crane has sought to refute four main arguments proffered by the car dealers’ lobby: that direct distribution bans are a form of “consumer protection” against monopoly, inferior aftermarket service, and recalls, as well as a safeguard for the philanthropic role independent dealers often play in their communities.

In countering the monopoly claim, Crane calls upon the economic principle that if a manufacturer has market power in its brand, it will extract the full monopoly profit regardless of whether it sells to dealers or end users. The cost of retail distribution will be fully embedded in either the wholesale or resale price.

“If anything, outsourcing the retail distribution function to locally dominant automobile dealers could lead to double marginalization and increased prices,” Crane argues.

He also challenges the supposed correlation between dealer distribution and superior aftermarket service, calling it a “question of incentives” and reasoning that “Tesla is investing billions of dollars in its brand, technology, and infrastructure to create demand for its product. It is not going to recoup a huge investment if it doesn’t provide service for its cars.”

Similarly, he points out that only manufacturers and federal regulators make the decision to issue safety recalls, so “adding a layer of dealer distribution does nothing to create safer automobiles on the road or better recalls.”

Weakest of all, in Crane’s view, is the argument that independent dealers deserve special protection to preserve their philanthropic abilities.

“By making this argument, car dealers are admitting that this protectionism gives them special levels of profit that they can in turn spend in their communities,” Crane says. “What car dealers have to accept is the idea that the model they have relied upon for the last 60 to 70 years is changing and they have to adapt, but not by insisting upon a legally protected position.”

While state laws restricting direct distribution by automotive manufacturers remain prevalent, Crane says he has noticed a political shift in the national debate.

“Many of the frontrunners for the 2016 presidential nomination have started coming out in support of legislation that would allow direct distribution, and there is a raised consciousness at the state and regional level,” he says. “I’m optimistic of change at the state level but would welcome federal legislation. This isn’t only about Tesla. It’s a question of allowing innovative, environmentally friendly products to come to market and allowing consumers the option of dealing directly with the manufacturer.”

![The Tech [R]evolution in Law The Tech [R]evolution in Law](/sites/default/files/styles/teaser/public/2023-03/The-Tech-%5BR%5Devolution-in-Law.jpg.webp?itok=Obrll94p)